Illustration by Suhail Naqshbandi.

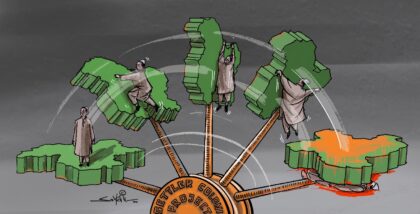

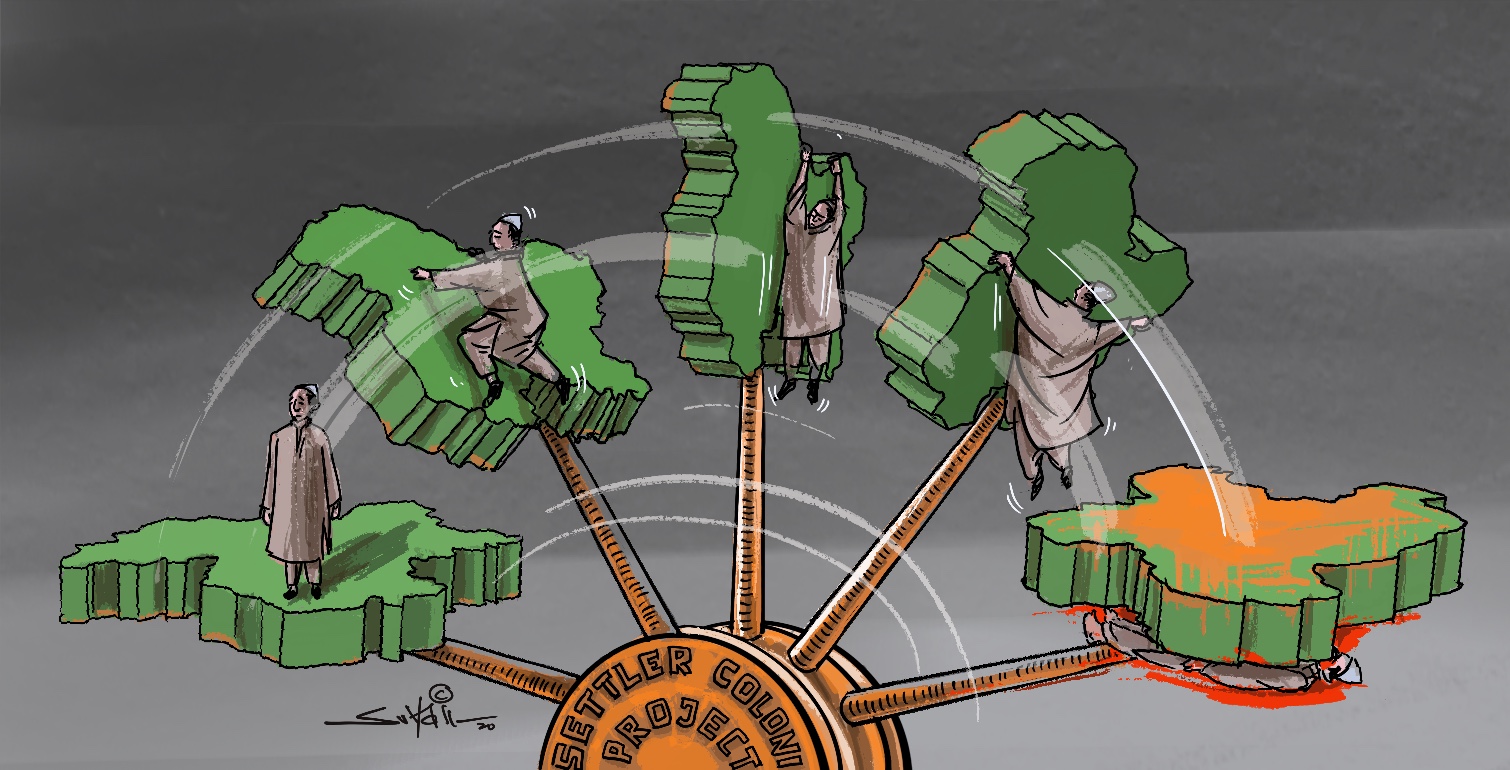

Illustration by Suhail Naqshbandi.

Tajamul and I, Tahir, hail from South Kashmir, the epicenter of political resistance in Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir. Although we are seven years apart, our experiences are entangled, like our respective districts—Shopian and Pulwama. Tajamul grew up among verdant apple orchards and glacial streams, and I in the vast landscape of undulating saffron fields. Destiny made us citizens of what is now called “the land of martyrs.”

We can relate to each other’s perspectives precisely because we are subjected to, and are the survivors of, the same structure of violence.

We belong to the generation of Kashmiris whose formative years, the 1990s, were a period of great turmoil and bloodshed, which shaped our political subjectivities and made us into the people we are today. We have never met, but we have read each other’s writings. We can relate to each other’s perspectives precisely because we are subjected to, and are the survivors of, the same structure of violence, which triggers our discursive and visceral responses, and which, as anthropologist Mohamad Junaid has written in a recent essay on state violence in Kashmir, induces “a hermeneutical instability within the social.”

Drawing from his personal circumstances, Tajamul provides a poignant account of his brother’s short-lived life. It is a narrative that lays bare the vicious edifice integral to the Indian colonial rule over Kashmir and Kashmiris. I narrate my experiences of seeing the aftermath of August 5, 2019, when India imposed an unprecedented military siege on Kashmir to dismantle Article 370, the facet of the Indian constitution that had enshrined Kashmir’s fragile autonomy.

Tajamul

I was born in September 1992 into a farming family in Nazneenpora, a small village located in the district of Shopian. My brother Ruban and I grew up listening to tales of gun-battles, bloodshed, brutal crackdowns, and harassment of my fellow Kashmiris by Indian soldiers. No matter how hard I try, I cannot get these memories out of my mind. I still recall the late 1990s, when Indian soldiers would lay siege to our village and order all male residents to assemble in a school playground. Terrified at home, kids and women would wait anxiously, fearing for the life of their loved ones in the open sky and under the mercy of the Indian army.

I also remember young and restless boys marching on village roads with AK-47 rifles. They would tell people that they were fighting for their future, for our future. I also recall the boys who vanished one after another fighting the mighty Indian army. It was a difficult time to be a kid.

By the early 2000s, it became normal to walk past military garrisons manned by intimidating armed soldiers, and be stopped and frisked. Sometimes, we were beaten for not carrying our identity cards, or for simply being at a wrong place at the wrong time. Indian soldiers were everywhere: on our hillocks overlooking our villages, inside our orchards, in abandoned factories and houses, in our farms and fields, on roadsides, in the lanes and by-lanes of cities and towns, by the rivers and streams, and in the mountains. A panoptical nightmare.

After the Kargil war between India and Pakistan in 1999, things had started to cool down in Srinagar. But, not much changed in the countryside. For the time being, guns seemed to have fallen silent, but that didn’t alter an ordinary Kashmiri’s life. We were still living inside a big garrison.

Indian media touted the relative calm in Srinagar and a few major urban centres as “normalcy,” eliding the reality of the hinterland where Indian soldiers were altering the geography of villages permanently.

The 2008 and 2010 street protests marked a shift in the Kashmiri resistance. Guns had been put down. People saw hope in large protests. Social media helped young Kashmiris reach out to the world with their stories and plight. They were sure the world would intervene. Mobile phones and the internet had changed our lives. We were no longer isolated in our villages surrounded by Indian soldiers. We felt empowered. But Indian forces cracked down on our nonviolent protests, killing dozens and maiming thousands. Once again, Kashmir was staring at an uneasy status quo.

Two years later, in 2012, I visited the Indian city of Chandigarh with the intention to spend some “peaceful” time there. My brother Ruban stayed back to finish school. I ended up enrolling in an MBA program at a private university. By the time I came back in early 2016, Kashmir was a different place. Posing with an AK-47 rifle in the jungles, a charismatic teenager named Burhan Wani had captured the imagination of many Kashmiris. He was hero-worshipped by younger people. From the hideouts, the militancy in Kashmir had moved to social media platforms.

Wani’s death in a gunfight on July 8, 2016 changed the course of events in Kashmir, and for me and my family. It inspired a new age of militancy, with hundreds of young Kashmiris joining different militant outfits to fight the Indian occupation. My cousin Naveed, too, became part of this fresh wave of armed resistance.

Naveed was a cop, but when his friend Farooq joined a rebel group in September 2016, Naveed joined as well in 2017. Since Naveed was our relative and Farooq was Ruban’s close friend, the Indian army often raided and searched our house. Our family was continuously harassed and asked to give information about the militants.

In the first week of January 2018, my father received a call from the Station House Officer (SHO) of the police station nearby. He was asked to bring my brother Ruban, who was 18 years old at the time, to the police station. Once there, he was told to come back later in the evening to pick him up. When my father returned, the SHO informed him that he had been shifted to “Cargo”—a military garrison and notorious torture centre in Shopian. When my father asked them about the charges, he was abused and humiliated.

I was in Pune, India at the time. My mother called me, narrating the whole incident. The next day, I booked a flight and travelled to Srinagar. For the next eight days, I knocked at the doors of the Administration, from police to bureaucrats to anyone who I thought could help. I was dragged from post to pillar. The only reply I received was that “we will see.” But nothing was done. No police report registered. Under what charges was my brother arrested/detained/abducted/disappeared, I asked?

I managed to contact a sympathetic legislator, Engineer Rashid, who accompanied me to Shopian, where we held a sit-in protest in front of the police station against the illegal detention of my brother. We succeeded in getting Ruban back alive. His legs had marks of hot iron. He had been brutally tortured inside Cargo. It took him two months to stand up on his own. I convinced my mother to send him outside Kashmir. She agreed, and he came with me to Chandigarh.

Not three weeks had passed before the Indian army came to our home in Nazneenpora looking for my brother. My father was asked to bring Ruban back from Chandigarh. I left my job and we came back to Kashmir. One night, the Indian army raided our home. Our family was tortured. I was beaten, too. I vividly remember an army officer telling Ruban, “You have a beard, a cap, and you pray five times—why don’t you join your cousin Naveed?” This army officer then put an AK-47 rifle on Ruban’s shoulder and took his picture.

On July 18, 2018, my brother was again tortured, this time by the Indian army’s 44 Rashtriya Rifles and Jammu and Kashmir Police (JKP). His story appeared in the local English daily, the Kashmir Reader. Yet, no enquiry was called, and no justice was provided. As harassment and torture continued, my brother was pushed to the wall and he couldn’t take it any longer. He was left with no choice but to pick a gun at a very young age. He saw death as a better alternative than a life of pain, subjugation, and continuous harassment by Indian soldiers and the JKP. Eventually he left home and joined a militant outfit.

Seven months later, we received Ruban’s dead body. He was killed in a nightlong gun-battle with Indian soldiers in the forests of eastern Kashmir’s Budgam district. He was buried according to his will, beside the grave of his best friend Farooq.

Tahir

On the evening of August 4, 2019, I called my mother from the bazaar and told her that I was getting a bag of flour from the grocery store. She asked why. I told her it felt like something big was going to happen. As you wish, she said.

I went to a couple of groceries but couldn’t find flour. At last, a shopkeeper got a bag for me from his home. People were stocking up, but we didn’t really know for what—though rumors were rife that the Indian government was up to something bad. I sensed that India might launch a war to capture Azad Kashmir—Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Earlier in the day, on the heels of the Indian side allegedly using cluster munitions to target Azad Kashmir, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan had promised to respond to any “misadventure or aggression” by Indian forces. He also tweeted asking the US to intervene lest the deteriorating situation in Kashmir “blow up into a regional crisis”.

The people who came from peripheral villages to visit the hospital in our town brought little pieces of information.

Oblivious to this geopolitical turbulence, people in the bazaar speculated about something more domestic. “I heard they will remove 35A and make Kashmir a Union Territory,” said a customer at the grocery, asking for an extra pack of cigarettes. “I heard,” said my friend, “they will snap all communication and only 500 satellite phones will work.” He had, like everyone else, received leaked official orders on WhatsApp, including the one asking Indian pilgrims and tourists to leave the region as soon as possible.

At all the gas stations, long queues of vehicles waited for their turn. I pulled out my phone and captured the scenes. When I told my brother that we should also get our car filled with gas, he asked, “Are we going to picnic when the war breaks out?”

At night, I continuously checked for updates. Social media was filled with speculations, increasing our anxieties moment by moment, until midnight struck and all the phone and internet lines went kaput. I couldn’t sleep. Worst case scenarios started dancing in my mind and wouldn’t leave me at peace.

The next morning, my cousins, uncles, aunt, and almost the entire extended family huddled together in front of the TV. We watched as the Indian Home Minister rose in Parliament holding a piece of paper in his hands that were uncharacteristically shaking. He declared that Article 370 had been revoked by a presidential order, and Kashmir was split and demoted into two federally-administered territories. The rumors, after all, turned out to be true. A pall of gloom descended in the room. Saba and Madiha, my younger cousins, turned to me and asked in a low voice, “What will happen now?”

“This will change our demography in the long term, and we will lose jobs to nebrim [outsiders] who can apply now,” I told them.

Curfew was imposed outside. Roads were sealed with spools of concertina wire. Soldiers were everywhere. For the next five days, paramilitary men remained stationed at the mouth of our street, menacingly waving their long batons to tell us to go back to our homes. Our mobiles and landline telephones were dead. We were completely cut off from the rest of the world.

The people who came from peripheral villages to visit the hospital in our town brought little pieces of information. They told us that the paramilitary and army had imposed a reign of terror across south Kashmir villages. In nocturnal raids, young boys had been taken away. Many of these detainees were sent to different parts of India, as the space in Kashmiri jails had filled to maximum capacity. I learned from my journalist cousin, who works for an English newspaper, that in Srinagar’s Soura suburb over 100 protestors had received pellet injuries on their bodies at the hands of Indian forces.

I was able to leave Kashmir in the second week of September. After landline phones had been restored, I went to my father’s uncle’s house and called a relative, Adil, who was in Delhi. I asked him to book my tickets.

It was in Delhi that I got a better picture of what was actually happening inside Kashmir. The Washington Post, New York Times, Al Jazeera, BBC and a host of independent Indian news portals had published report after report, documenting cases of torture, deaths, injuries, mass detentions, and severe restrictions on local media. I realized I had been living in a dystopian world.

Although the Indian government told the world that the Kashmir lockdown was a temporary measure, it dragged on and on, until people started to realize that all this was actually a collective punishment for demanding the right to self-determination. And what could be more thrilling for the Hindutva supporters than seeing Muslims, particularly Kashmiri Muslims, doubly marked, suffer under a humiliating military siege. They celebrated by dancing on roads and distributing sweets when Article 370 was revoked. Many centrists in India were also happy. Some Indian men believed that now that Kashmir was fully subjugated and thrown open for outsiders, they could get fair-complexioned Kashmiri women as the spoils of war.

Naturally, such comments made Kashmiris extremely upset, but also increased their resolve to resist. And resist they did, for more than three months, by observing civil disobedience, which entailed that for many weeks, businesses and schools would remain shut and attendance in government offices thin. I could see that my father was expressing himself quite politically for the first time by saying that we must make this sacrifice. He runs a small shop in the bazaar that sustains five members of our family. The shop remained shut for those three months, opening only for two hours daily based on an arrangement called “deal” in local parlance, consensually decided among Kashmiris. On many occasions, even the two-hour window for business was denied by the sudden panic and commotion in the bazaar created by mysterious firecracker bursts and stone-pelting.

One of the ways of making the sacrifice was eating a lot of bottle gourd and collard-greens, which grows in abundance in Kashmiri kitchen gardens. Planned weddings were either postponed or done without pomp, with the guest list whittled down to a few dozen people. I saw women of my town nervously wait for shops to open and then quickly buy wedding and other personal stuff during the deal hours. With access barred to online shopping, procuring diapers for my little one became a challenge.

Sustaining the civil disobedience was difficult, however, so eventually it seemed to fizzle out, partially under the economic pressures. The same had happened during the 2016 anti-India uprising. By October 2019, a false sense of “normalcy” had returned, though we knew it was suspect.

There’s a set of concrete steps along the shops near our house, where, if police are lax, we typically bide our time sitting during curfews and shutdowns. We call it “pend,” and it was here that I heard that the government had given money to vendors and asked them to set up their stalls on certain strategic locations of the Srinagar city to create an impression of normalcy. Policemen in civilian clothes, it was said, were driving cars to reinforce this contrived situation.

The most remarkable part of sitting at the pend was listening to stories from those who had intimately experienced the early years of the armed insurgency. Pend became an occasion to recall past heroic deeds, betrayals, and missed opportunities. Sheikh Abdullah, the Kashmiri leader who strongly opposed the idea of joining Pakistan 1947, was profusely cursed, while Burhan Wani praised for keeping the resistance alive. Masterji, a scrawny retired school teacher, felt that Kashmiris were gabbi (lambs), and didn’t possess the true spirit of faith like the Afghans, who brought the superpower America to its knees. War was indeed on every person’s mind; it had become almost a collective wish.

I cannot forget what my father’s uncle, Ba’jaan, told me when we were driving through the bazaar one fine day. “Look around,” he told me, “look closely at the faces of people. Can you find anyone with even a semblance of happiness on his face?”

I nodded but said nothing.

“Kasheer gai waraan,” he said. Kashmir has been turned into desolation.

Indian bureaucrats issued regular statements saying how things had improved and Kashmir was limping back to normal. The regime supporters claimed that Kashmiris were happy with the decision. Everything will be fine in “New Kashmir” now, they told the Indian public. “You see Modi-ji has taken a big step for Kashmiri’s development. Ambani is going to finance education of all Kashmiri kids born after August 5,” said my middle-aged cab driver while driving towards Delhi Airport. I didn’t even bother to tell him that it was fake news. Being a little timid, I avoided talking politics with him, while he felt entitled to blabber and say that all Kashmiri leaders must rot in prison.

Almost every evening my brother and I, along with my cousins, gathered in Ba’jaan’s living-room and watched a debate program. In one rare instance, Kashmiri journalist Syed Nazakat made a touching remark to which we all nodded. He described how Kashmiris were in utter shock that we didn’t know what was happening to us, and warned against seeing the absence of protests as acceptance of the government’s decision.

***

Writing and documenting this loss is an act of courage that can only arise from the belief that these deaths have meaning and won’t go in vain.

The siege since August 2019 has hurt us deeply. Our economy has suffered enormous losses. Start-ups died, mental health issues became widespread, scholars could not carry out their research, students couldn’t download study material. Those who could afford to moved outside Kashmir, but most couldn’t, and they continue to face endless hardships.

As Tajamul and I reflect on South Kashmir and its suffering, Kashmiris are staring at a bleak and terror-ridden future after the Modi regime—exploiting the crisis occasioned by Covid-19 pandemic—forcibly imposed a new domicile law that fast-tracks the process of the Indian settler-colonial project in Kashmir. Kashmiris fear that their homeland will be turned into South Asia’s Palestine.

These losses are close and personal. Tajamul is again in a state of mourning. On Thursday, June 18, 2020, his younger cousin, 17-year old Syed Shakir Shah, died fighting Indian forces in Shopian. Shakir had joined the armed resistance just 16 days before. Including Ruban’s funeral, Tajamul has now shouldered five coffins: his brother, cousin, and three friends.

Writing and documenting this loss is an act of courage that can only arise from the belief that these deaths have meaning and won’t go in vain.

No week passes without the death of yet another young Kashmiri. Every death is felt as a shared loss in Kashmir. The occupiers would prefer that we bear it silently. Yet, our existence is at stake and silence is not an option.