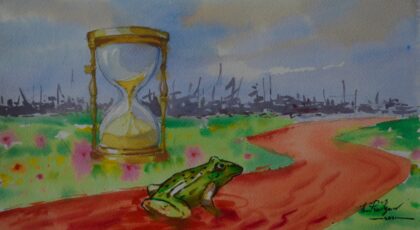

A poet doused in gasoline, burned to the ground. A girl shot dead while sitting on her father’s lap. Bodies in a temple, piled high.

While a regime’s capacity for violence can seem unfathomable, so too is the strength of those defying its heavy hand.

In this issue, we feature voices of rebellion and rage, pain and possibility, from writers and artists on the front lines of resistance in the aftermath of the military coup in Myanmar on February 1, 2021.

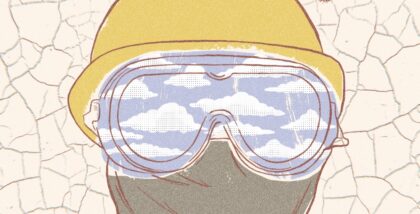

Since the military seized power, mass protests have surged unabated, even as the junta sustains a ruthless crackdown on its citizens. In the months since the coup, more than 800 civilians have been killed by security forces.

Through fiction, poetry, and analysis, the pieces here speak to a historic and multifaceted swell of resistance, from writers on the ground, accompanied by powerful original illustrations from Myanmar-based artists JC and Thu Ra Kyaw.

We are honored to publish a series of short stories, written in the aftermath of the coup, by four women—Sabal Phyu Nu, Nay Cho Aye, Thawda Aye Lei, and Yu Ya—from a range of ethnic communities in Myanmar. The stories, translated from the Burmese by Eindra Ko Ko, are stark, intimate glimpses into the uprising unfolding alongside the uncertainty and agony of life under martial law. “The more wicked and unwanted the spirits,” writes Thawda Aye Lei, “the longer and harder you have to beat.” The stories were commissioned in collaboration with writer and literature programmer Lucas Stewart, who offers some additional words of context below.

Michael Shaikh, who previously led the UN’s investigations into the Rohingya genocide, interviews the prominent Burmese journalist Thin Lei Win about the tenacity of the opposition and the prospect of a grand compromise among the country’s long-divided ethnic groups. “We never had a real chance of forging a common identity that has not been imposed by the junta or the colonial masters,” says Thin Lei Win. “Now, there could be a real chance for nation-building.”

And Stella Naw, a Kachin activist and new member of Myanmar’s National Unity Government, which formed in opposition to the coup, considers possibilities for an inclusive society now that the majority population “has seen the military’s true colors.”

You’ll also find poems of dissent, anguish, and hope forged from the raw turmoil of the last few months, several of which were translated from the Burmese by ko ko thett.

Mi Chan Wai probes how the military wields paranoia: “Foe has no label / written on his forehead. / But he is close. / Very close.”

In a piece dedicated to a young girl killed by a bullet that came through the bamboo wall of her house, Min San Wai writes, “Today each and every person in this country / has a tiny hole as big as a pencil tip / in their chest.”

Rohingya writer Ro Mehrooz contemplates liberation in a world where “dogs masticate the bones of humans.”

And the words of K Za Win, in his final poem before he was killed by security forces this spring, burn incandescently: “The Revolution won’t materialize / out of your mere thoughts. / Like blood, one must rise.”

—Meara Sharma, Adi editor-in-chief

The four short stories in this issue were written in the first few weeks after the military coup in Myanmar. Three of the pieces feature characters participating in street protests. Two of the stories are set in Sanchaung, a vibrant central township in Yangon, with tight streets, raucous beer stations, wonderful clothing stores, and close-knit residents, including ethnic communities, especially the Chin and Kachin.

On March 8, protestors played a game of cat and mouse with the security forces, dispersed by tear-gas and bullets into nearby streets and alleys before reappearing again elsewhere. By late afternoon, security forces sealed off a section of the township, trapping hundreds of protestors finding sanctuary with residents in flats overnight. While more than a quarter of the protestors were discovered and taken away, many others escaped the following morning.

The siege of Sanchaung marked an inflection point in the popular civic demonstrations against the military takeover as peaceful protests spiraled into urban warfare, pitching civilians against soldiers. These stories are just the beginning of the narrative of a nation defiant in the face of, as Nay Cho Aye writes, “the lies, the ruin, and the deaths it takes to keep one man in power.”

In this Issue

Raising our Flags High

A Kachin activist on reimagining an inclusive society after the coup in Myanmar

Thin Lei Win: Nobody Wants A Compromise

The Burmese journalist on how Myanmar’s military is “wrecking everything” to hold onto power, and the popular uprising trying to stop it.

The Fight for Rightfulness Will Be Victorious

I know your pain when you see dogs masticate the bones of humans, / when you see guns and imagine mountains of dead bodies

I Will Be Back Soon

There must be hundreds of us hiding tonight. We all have mothers, fathers, and children expecting us to come home.

In the Heat of Laughter

Kyaw Kyaw’s optimism was anchored by a single, naive belief: that a savior will come.

Hide and Seek

I don’t want to be another father watching another child grow among the lies, the ruin, and the deaths it takes to keep one man in power.