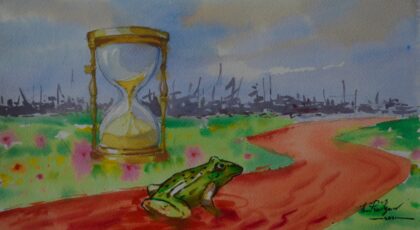

Art by Thu Ra Kyaw

Art by Thu Ra Kyaw

Translated from the Burmese by Eindra Ko Ko

A pack of dogs chase us along Kyun Taw Road. The tear gas makes my eyes burn so much that I can barely see where I am. We are running and running. People behind and beside and in front of me are running. “Don’t run. Don’t run,” the dogs howl, and then shoot. They have body armor, I have a backpack. I hunch, it’s a reflex every time I hear a crack. I hunch because my body thinks it has been shot.

I am 33 years old, born in the year of the 1988 revolution. My father protested every day that year, he walked in the sun from Insein to Sule. I ask myself a question: Am I going to die? But my father didn’t in the year I was born, so why would I die now?

I enter the alleyways. One house has a door half open. There is a boy standing there, he looks about 18. He is shouting, “Come in, brother.” Me and the people behind me run toward him and he slams the door shut to somewhere dark and cold. I feel dizzy and my eyes hurt. I pour Coca-Cola over my face and wash the soda away with a bottle of water. There is another crack of a rifle outside and then I hear a lady asking if everyone is ok. As my eyes clear, I realize we are in a shop. I count 14 in total, 11 of us and three shop-workers, young women.

The rifle snaps outside continue while the staff hand us some bread-buns wrapped in plastic. “There is no rice, only buns and water,” they try to apologize, but we tell them how grateful we are, not just for the food, but for letting us in. “Don’t thank us,” they say, “thank our boss. He called us and told us to help you if we saw you.”

Isn’t everyone afraid to die? I try to convince myself that is why others barred their doors to us before. They are afraid to die. I don’t blame them. But I do feel sad. It’s complicated. It’s not as if they don’t know why we are doing this. There is a reason.

*

It is now evening. Usually at this time the pack retreats somewhere to eat, but not this night. The dogs don’t like Kyun Taw road. It’s a stubborn place. Even as the dogs set off smoke grenades in the streets, some of the residents spill out and walk and sing in the gloom. We can hear them as we eat our snacks, but so can the dogs and then the chanting is broken by more rifle cracks. If they want to break us, first they need to find us, so the dogs search from one house to the next. The door to our shop rattles violently. One of the staff tells us to hand over our rucksacks, which she hides among the shelves and cupboards. Another leads us towards the back of the room to a small hatch in the floor which she lifts up.

“There is nothing in there, except mosquitoes,” she says. “Get in, get in.”

We clamber through the hole into a storage basement. The hatch closes above us and something heavy is dragged across it. I can feel the damp around me, but I can’t even see the walls, it’s so dark. One of us starts to softly cry, so we turn on our phones. It is a girl in the corner. She stops and looks back at us all and in the now too-bright glare of the phones I realize how young everyone is.

I am the only father and husband here.

Before I left, my wife put her hand on my head and prayed for good fortune. She wanted to come. She thinks that if we are to die it should be together but she has trouble walking, let alone running, so we decided it was better for her to stay with our child.

The mosquitos are unbearable.

I can’t stop thinking about my death. My wife often talks about the embrace of God. I’m an atheist so it’s not usually something I worry myself too much about. Not until recently anyway. I decide, if they find us, it might be nice to be with Him.

Someone laughs. It is only a small thing, something you wouldn’t even notice on another day, but in that hole, the sound of something normal is a relief.

There’s a scraping sound above us. The hatch inches open, and a voice says, “They’ve left. They’ve gone to another house. Don’t worry.”

The hatch falls back down and I sink to the floor. I haven’t sat down all day. My bones crack at the joints as I stretch out. I turn to the others and say, as loud as I dare, “Hey you, we’re not political prisoners yet, just political fugitives.”

Someone laughs again, but then stops so we can listen to the shouting that erupts outside. It’s a large group of people, probably residents. I can hear monks among them requesting the dogs to let us leave Sanchaung. I know we are trapped, but there is a still moment when I hope the dogs will change their minds. The moment passes. The monks leave and a little while later the shooting starts again.

*

I cannot sleep, so I turn on my phone. My social media feed is full of unsteady videos taken from uncomfortable angles. I tap on one. Someone in Sanchaung is livestreaming people being dragged out of an apartment and forced to kneel on the ground. The phone flashes and tells me my wife is calling but I can’t stop watching the video. One dog is clubbing them over the head with his baton. Another comes and kicks them while they are still kneeling. The phone flashes again but now they are getting pulled up one by one and shoved into the rear of a truck. It’s then I recognize the street; it is only three blocks away from the hole I’m in.

Since I haven’t answered her call, my wife sends me a message. It’s the phone number of an embassy. Apparently, they have made a statement making it known they are aware of what is happening in Sanchaung and are demanding the dogs are called off. My wife seems to think they might come and pick us all up. I know she is worried and is trying to do anything she can to help me. For perhaps a second, I do consider calling the number, but no one from an embassy is coming for me.

I am actually more worried about her. If I am found and the dogs take me away from this hole, what kind of place will I leave my wife and child behind in? She’s from a Karenni village, so she is familiar with these dogs. When she was growing up, the Mother-Chiefs were in charge, since all the men in the village had either been taken by the dogs or were living apart in the forest so they wouldn’t. But the dogs would come again anyway for the Mother-Chiefs. This is the type of life my wife came from. If I go, she will be the Mother-Chief of our child. If they take her too, then who is left? There are people we know who would at least feed our child, but I am not sure about them. Instead of forests, they hide in their flats. Other people did the same in the year I was born and now the dogs are back in the city.

This morning, my wife told me we should consider running away, to some other country, whichever one would let us in. Perhaps, but not yet. There is something I want first. Or don’t want. I don’t want to be another father watching another child grow among the lies, the ruin, and the deaths it takes to keep one man in power.

*

“Brother, seriously, how do you expect any of us to get any sleep when you are snoring so loudly?”

I slapped his hand away in anger when he first touched my shoulder and woke me up but I see his smile and start laughing with everyone else. I sit up with my back against the wall of the hole and check the time on my phone. 3am. I try to check my social media again but then remember the dogs cut the internet off at 1am every morning. Still, texts are working and my wife has sent many in my sleep. I send just one back: Don’t worry. I’m fine. I’ll be fine even if they take me.

The hatch creaks open again above me and the same young girl says, “It will be sunrise in another hour or so. When people start going to the markets, we can sneak out then.” There is a chorus of thank yous from the hole, but just before she closes the hatch we all hear the gunshots.

I just don’t know how we can hope to escape if they are still on the streets shooting. A young man next to me confirms to us all, as if sensing my hesitation, “We will try to get out at dawn.”

If we are to do so, then we need a plan. As the eldest in the group, I try to take the lead but the younger ones start debating about tactics and strategies they learned while playing some online game they called Players Unknown Battleground. I have no idea what they are talking about, so I sit aside and listen and feel my doubt give way to hope.

The mosquitos are still unbearable. But I can’t wait for the morning.