“we forget we / remember one history / to forget another,” writes poet Philip Metres.

These lines introduce Anna Badkhen’s essay, “In Memory of Memory,” part of Adi’s 11th issue, Contested Histories. Recounting her grandmother’s escape from Leningrad during the harrowing 1941 Nazi siege, Badkhen contemplates how memories of conflict wend their way through generations and inform how we distill stories of suffering into history. “Memory is a contested terrain,” she writes, a realm that is endlessly making and remaking us, resisting fixed ideas of truth and falsehood, shaping how we understand ourselves and each other. Badkhen asks, “Are we prepared to accommodate all of the stories?”

Across this issue, the mutability of memory is both a source of peril and potential. From a refugee family’s efforts to invent a new life to a pernicious myth about climate change, this collection of pieces reminds us that history is a creative act, forged in the heat of questions and doubts, desires and fears.

Vi Khi Nao revisits her family’s journey from war-ravaged Vietnam to the American midwest, considering how freedom and debt are fractured mirror-images. “My father doesn’t owe anyone or anything. He doesn’t have any credit card debts. No car payments. But this freedom from debt enslaves my father.”

Poet Enbah Nilah revises the meaning of “generational wealth,” casting displacement as a poignant family heirloom. “My father carves with a pen / with the patience / inherited from his father, / sculpting scissors-over-comb / in a sweltering barber shop.”

Ayuujk activist Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil critiques the identity category “Indigenous,” arguing that it reduces distinct histories and peoples into a tale of conqueror and conquered. “Systems of oppression dole out many notions of identity on platters, ready for consumption,” she writes. “The word Indigenous has been affixed so firmly to our faces that it becomes a mask that tries to pass itself off as skin.”

Annia Ciezadlo sets out to debunk the view that climate change was the primary catalyst of the 2011 Syrian uprising, situating this narrative in the context of hundreds of years of agricultural history and examining how its persistence entrenches inequality, fuels xenophobia, and exonerates the powerful. “The idea that growing too much food could result in hunger is so counterintuitive that it’s almost impossible for most of us to grasp,” writes Ciezadlo. “But strange though it may seem, what happened in Syria is exactly that.”

Chanelle Adams traces the journey of the camphor tree across continents and empires, exploring how this coveted resource became, in its various adopted homes, a symbol of both destruction and resilience, conquest and community. “Carving out a role in each new soil, this opportunistic tree is a place-maker,” she writes.

Craig Kenworthy, in a piece of short fiction, inhabits the mind of a political prisoner whose punishment involves being deprived of meaningful information. “Like everyone else suffering through the war, he would wait for it to end but, unlike them, he would not know how long he had waited. Never know the first sunrise of a ceasefire, or witness the turning of the page from conflict to peace.”

Habibe Jafarian, from the midst of the current women-led political transformation in Iran, critiques the pervasiveness of “pity” that marks Western performances of solidarity and affinity with her people, “We have always been walking on foot, as the proverb says, and seldom have we received anything of real value from the rider who happens to be passing by.”

Meanwhile, Iranian-Swedish poet Athena Farrokhzad, in an excerpt from her new book, Donkey Days, (Albert Bonniers förlag, 2022), explores the nuances and tensions of resistance as they unfold in the spaces of family, self, and collective space: “We will gallop through the streets, cry like crows from the rooftops / that God is great and greater than God is the wrath when we gather.”

Hawa Allan unpacks America’s existential crisis through the lens of Kyle Rittenhouse’s trial by excavating the tensions in the creation myths of American citizenship. “Today, in the United States,” she writes, “we are shadow-boxing with the archetypal after-effects of two prototypes that emerged during this early, peculiar history—what I call the Lawman and the Outlaw —as well as each one’s shadow aspect, the Vigilante.”

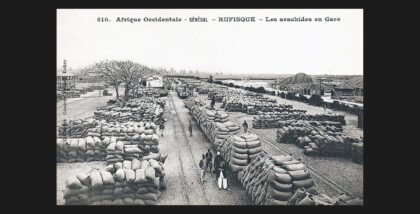

Finally, we are thrilled to celebrate the release of Slaves for Peanuts with author Jori Lewis, Adi’s own Senior Editor. In this interview, we dig deeper into her research and writing process behind the book, which interrogates the much lesser known history and political economy of enslavement in West Africa, and the complications (complicities) of abolition in the transition from colonialism to capitalism. Lewis questions the singular narrative of triumph associated with freedom: “I think we have a tendency to say, “This is right. This is wrong.” With free labor versus slave labor—obviously slavery’s wrong. But is being a free laborer enough, if you’re forced through your economic circumstances to indebt yourself, or live hand to mouth, or work as a sharecropper with no hope of getting out from under that yoke?”

—Meara Sharma, outgoing editor-in-chief & Cynthia Dewi Oka, incoming editor-in-chief

In this Issue

A Soundtrack to Issue 11

We asked each contributor to Adi’s eleventh issue to share a song that resonated with their piece. From Anna Badkhen’s

Excerpt from Donkey Days

But will there really be a revolution after the night of revolution // and will it belong to our daughters if it comes

Because of the Droughts

The idea that climate change triggered the Syrian uprising is a persistent and dangerous myth. What really happened?

The Trail of The Camphor

What a resilient medicinal tree reveals about the entanglements of botany and empire.

In Memory Of Memory

Who is to judge, as we pick our way through history, move across the borders of memory, what is true and what is false?

We Were Not Always Indigenous

The word Indigenous has been affixed so firmly to our faces that it becomes a mask that tries to pass itself off as skin.

Peace Criminal

Box would answer any question Acen asked it. Unless it involved what he most wanted to know: what day, month, season, or year it was.