Art by JC

Art by JC

Translated from the Burmese by Eindra Ko Ko

He calls himself Kyaw Kyaw but that’s not his real name for reasons I will explain properly later. It is a joke, as everything is to Kyaw Kyaw. Humor is his way of dealing with issues in his life. It keeps him positive, so he says; humor is healthy for us. While there is a small part of me that wishes I could make fun of life no matter what happens, I’m far too rational for that. There are degrees, of course, some trivial things which we could let overwhelm us if we didn’t make light of them, but I am not so absolute as my friend. I believe there are things out there, some events, some happenings, that are too terrible to be reduced to a laugh. To do so, making small of something so large, seems insulting to me.

Kyaw Kyaw disagrees. On the first day of February, we had the misfortune to see who was right.

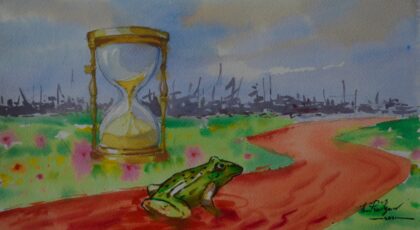

It was the last day of winter. Spring was supposed to come next, but we fell straight to summer. Any blossoms that had sprouted curled and withered in front of us. The water we drank and washed in evaporated under a new burning sun, while the fish flapped in desperation on dried, cracked riverbeds.

I tried not to cry, but the despair was too much for me. I was devastated. Even Kyaw Kyaw was miserable, at least for one evening. But then he was back to his usual self.

“What’s wrong with them?” he said. “Trying to take power through force. They can’t do that. Only the people can give you power.”

Even though Kyaw Kyaw is my friend and I know what he is like, his indifference still made me angry.

With little hope left in me, I took out my fury on a cooking pot at exactly 8pm every night. It’s an old custom; the harsh clanking of a spoon pounded on metal terrifies evil specters and forces them from your home. The more wicked and unwanted the spirits, the longer and harder you have to beat. Across the country, this would go on for 15 minutes.

It wasn’t long before our pots and pans were ruined. Kyaw Kyaw laughed one night, holding up a bent and pockmarked lid that could have come from a bin: “You know these things could become historical artifacts. We should keep them. Might be able to auction them one day.”

It was easy for the security forces to catch Kyaw Kyaw. Unlike the rest of us who stayed in our flats to drive the devils away, Kyaw Kyaw took his warped instruments out into the middle of the street where the devils could hear him better. Over the clanging that spilled from the open windows of every flat, the security forces informed him he was disturbing the public and took him away.

We, his neighbors, gathered outside the police station for over an hour, demanding they return him to us. Later, we learned there were two other men from another ward with him, and Kyaw Kyaw had somehow convinced them to play along with a stunt he had thought up.

The senior officer spoke to Kyaw Kyaw first:

“What’s your name?”

“Kyaw Kyaw.”

“And who are you parents?” the senior officer asked.

“My father is U Ba and my mother is Daw Hla.”

The senior officer then spoke to the second man:

“What’s your name?”

“Maung Maung.”

“And your parents?”

“U Ba and Daw Hla.”

The senior officer turned to the third man:

“Name?”

“Tun Tun.”

“Parents?”

“U Ba and Daw Hla?”

The senior officer looked at the three men.

“Are you brothers?” he asked.

“No,” the three replied in unison.

“Then how do you have the same parents?”

Kyaw Kyaw answered, “We don’t. At school, when we learned English, our teachers only gave us three names to choose from and one mother and father. Our names are either Kyaw Kyaw or Tun Tun or Maung Maung, and our parents are U Ba and Daw Hla.”

The senior officer stared at them in silence. I can’t even imagine what he was thinking, but eventually he handed over a document and said he would release them if they signed it.

As they left, the senior officer warned them, “I don’t want to see you here again. Don’t forget, I am also the son of U Ba and Daw Hla.”

Kyaw Kyaw was lucky. He was taken near the start of the protests. Later, the monsters were let loose at night. Criminals roamed the streets. Houses were set on fire. Curfews were imposed. Each day was worse than the one before, and all I could do was cry, curse, and click my tongue in bitterness. Kyaw Kyaw never changed though.

After our leaders were taken, we marched in protest for miles across the city. “My belly is too fat anyway. It’s about time I got some exercise.”

After Facebook and other sites were blocked, we all turned to VPNs and secure messaging apps. “Before, I didn’t know anything about this technology. Now, I’m like an expert.”

After the state media announced a new raft of rules and regulations, we could be arrested for any little thing. “I’m thinking of becoming a lawyer with all the new laws I’m learning about.”

After the internet was cut between 1am and 9am every night, we went dark to the world. “Good. Now I won’t stay up so late watching videos. I can get back to my normal sleep routine.”

After civilians were chased, beaten, and shot, we built defense walls across the streets. “If this is a game, we have levelled up.”

Kyaw Kyaw’s optimism was anchored by a single, naive belief: that a savior will come. No country, he thought, could watch what was happening and sit back and do nothing, as if a caped superhero from an American comic book would fly in and save us from the villains.

One day, I was seething with grief at the death of a boy from a deliberate shot to the head. Kyaw Kyaw came over to me. “The angels won’t abandon us.”

I just couldn’t bear it anymore.

“Are you an idiot, Kyaw Kyaw? There are no angels. And if there are, they aren’t coming. Nobody is coming. It’s just us. This is the nightmare. Stop dreaming.”

His eyes dropped but he didn’t turn away. When I finally stopped crying, he said, gently,

“Well, in that case, if it is just us, we need to prove that we are stronger than angels. Think about it, if everyone has a guardian angel and there are 50 million of us, then that’s over 100 million. And even if the spirits won’t help us, we are still strong.”

He began to laugh at his own words, but it wasn’t real. It wasn’t him. For the first time, he seemed to have listened to me. He didn’t say anything else for a few hours. And then, he laughed again. He told me he was going to help plan a new protest, something about scouting the entry and exit routes. He whistled as he left.