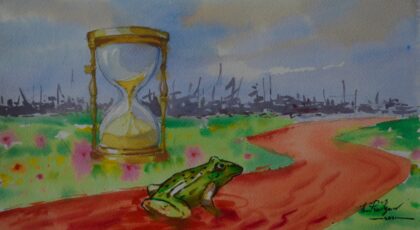

Art by Thu Ra Kyaw

Art by Thu Ra Kyaw

Translated from the Burmese by Eindra Ko Ko

The night isn’t normal anymore. It feels… different. Even though the yellow-bulbed street lamps are still on, most of the flats are dark as if nobody lives here. Actually, there are twelve of us in one of them. Two are the tenants, and the other ten are like me: temporary, hiding.

We are all in the bedroom as it’s the furthest room from the front door. We are huddled together on the floor, but I don’t know who is who. Is it fate that I should be with these strangers now? Can there be some other reason for why this is happening to us all?

It has been a while since I switched my phone to power-save mode, so I should still have quite a bit of battery left. The screen glows too bright in the dark but I can see the face of a three-year-old girl smiling. I touch the screen to dim the phone and think, dear daughter.

*

“Mum will be back soon.”

As I step out of my house, I turn around and kneel at the doorway. My daughter repeatedly says, “Mum will be back soon.”

She didn’t used to say that. I had returned to my old job when my daughter was only a few months old, so it wasn’t unusual for her to see me leaving and coming back. Sometimes, I had to be away for days and I would tell her I would see her soon and she wouldn’t even look up from her toys. Because she knew I would.

Now though, I don’t know what is bothering her. After I take a shower in the morning, she comes to me and says, “Mum doesn’t go anywhere.” It sounds like a statement, or even a demand, but I know she means, “Mum, you’re not going anywhere are you?” Once I am dressed, she keeps pressing, “Mum will come back soon.” This time I know she wants to say, “Please come back soon, mum.”

I stay on my knees and say, “Mum is just going out for a short while. I will come back soon. I will be back in the evening.”

“Mum… work?”

“Of course. Mum is going to work.”

I tell myself it’s not a lie. I do still go, but after February 1st, it’s not to the same place and I’m not alone.

*

I don’t want my daughter to grow up like I did. When I was her age, my home, Kachin State, was not at peace. I remember people shouting “run” and spending nights in shelters dug into the ground. When I got older, when they ordered one person from each house to come outside and strip the main road of any weeds and dead branches, I would take the knife so my grandma didn’t have to. I don’t forget the times I had to quickly pull my bicycle to one side of the road so a long convoy of dark green cars could fly past without hitting me. Or when I was told to wait on that road with everyone else for so long just to wave a flag and shout “be healthy” to every very-important-person who came and left.

I don’t want to live like that again. I don’t want my daughter to be afraid to live.

*

It’s called the “Spring Revolution” because most of them are so young.

“We are the young generation. We have a future.”

Those voices protest and thunder and thunder. They used to be students, still living in the shadow of their parents. First came COVID-19, then the hope of vaccines and some normality. But these nightmares that have come are not normal. Their parents and grandparents have told them of their own nightmares from not that long ago, and so they pay with their lives to wake up.

*

The sun in February is still weak. I don’t feel tired despite the crowd pushing around me. I’m watchful, eager but wary at the same time. We have already been hunted once today, but the residents in Sanchaung are good to us. When we run, they open their doors and tell us to come, to trust them. And they hide us and look after us as if we were known to them, though my own home is far away from here. Still, I come every day and sing to be free and call for peace with all these familiar strangers that share my heart’s anger. Then, I think, I will head back to my daughter in the evening like I have always done.

I’m not sure why they have begun shooting. We scatter into the nearest alleyways, unsure of where we are going, where it could be safe. Someone has opened a door into the side of a building and we follow him through it. I don’t know anyone around me, but we all move together up and up a flight of narrow cement stairs to the fifth floor. There, another door is opened for me.

*

“My mum will be looking forward to seeing me.”

It’s a whisper from beside me. The lights are off in the room so I can’t see the face but I can tell by the voice it is a girl younger than me. As far as I can remember they are all too young, except myself and the flat owners. I saw them as we all spilled into the single room, a mother, as old as mine, and her daughter, who could have been the same age as me. They didn’t look scared as they closed the door behind us all and then switched off the lights one by one.

But what about me? Am I frightened? Honestly, yes. We can hear the loudspeakers outside declaring that the neighborhood is being sealed off and they will come for us all later in the night. My daughter thinks I am coming home. How can I, if I am taken? I am not sure she will see me again.

And yet, I am less afraid when I realize I am not alone. There are nine others just with me. And then there are all the other blocks of flats. There must be hundreds of us hiding in Sanchaung tonight. We all have mothers, fathers, and children expecting us to come home.

Oh… there is a noise at the bottom of the building. It sounds like a door scraping against a wall.

The mother of the flat is standing. She says, “They will knock on the door and order us to let them in. But don’t worry, we will pretend the flat is empty except for us. We will do everything we can not to give you up, sons and daughters.”

There are heavy feet coming up the stairs. Boots. Then, a banging on the front door which doesn’t stop.

“Mum will come back soon,” I hear myself say.