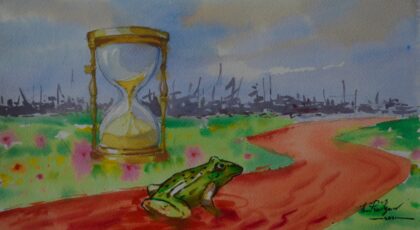

Photo courtesy of the General Strike Committee of Nationalities, Myanmar.

Photo courtesy of the General Strike Committee of Nationalities, Myanmar.

“Dogs are coming this way!” yelled a protester, referring to the junta’s security forces—police and soldiers. It was March 3, 2021, a few weeks after the Myanmar military seized power in a coup. With the warning, the crowd of about 50 people rushed to the side of the road for cover. I ran toward a line of trees and crouched down in the humid air. The sounds of gunshots soon followed. The sticky, mid-afternoon sun was high above and my heart was beating fast, not knowing what to expect next.

I remembered a friend’s place a few blocks away where I could find safety. As I made my way there on foot, I passed small groups of women and men gathered behind barricades, with slingshots, sticks, and kitchen knives held tight in their hands—the only weapons available to defend themselves against the security forces with guns roaming the city streets.

After 30 minutes of walking along the railroad tracks to avoid main roads and standoffs, I got to my friend’s place. A protester in his early 20s lay on the ground next door with a gunshot wound to his abdomen. His face looked pale; his blood-soaked hands were covering his stomach. He seemed calm and without fear. A team of volunteers carried him away to a hospital. Soon after, we were informed by a neighborhood watch volunteer that the “dogs” were heading in our direction to collect the injured protester. The few hundred people out on the street rushed into their homes again. Soon, the street was empty. My friend and I peeked through the crack in her front door, not daring to breathe. There they were, a dozen of them, fully armed in riot gear. At 5pm, my friend decided to lend me her bicycle so that I could return to my two-year-old son waiting for me at home. If I didn’t leave now, I was not going to make it back before the 8pm curfew. Security forces had recently killed members of neighborhood watch who were out too late.

I escaped the area, but eight people from the neighborhood were killed by security forces, adding to the nationwide toll of at least 30 that day. Soon after, the township was placed under strict military administration, which gives the military more local authority, including the judicial power to sentence protesters to death.

*

Millions of people from cities across Myanmar are in the streets protesting against the coup that took place on February 1, 2021, after the military declared the last general election a “terrible fraud.” Security forces have killed children, young people, and peaceful protesters, as well as politicians. Four months into the coup, the number of victims killed is nearing 1,000. Among them is a childhood friend of mine, KhuKhu. She was shot in her chest and died on March 28 while leading a peaceful protest in Kalay, a small town in Northwestern Myanmar. KhuKhu was a friendly and easygoing companion who became a devoted women’s rights defender until her last breath was taken away from us abruptly. Upon learning of her death, I locked my room and broke down screaming in tears. There was guilt, sorrow and anger bubbling up inside me. Why didn’t I stay in touch with her more often? Why didn’t I do anything more to keep her safe? Why…? There were many questions about what I should have or could have done. But I didn’t have time or space to mourn Khukhu’s death; my involvement in strike activities continued. We couldn’t afford to pause.

Though I’ve been frightened and angered by the violence of Myanmar’s security forces these last few months, it’s not the first time I have experienced the terror they perpetrate. I have long known what they are capable of, and how far their harm can go. As a member of the Kachin community, a Christian religious minority from the north of this Buddhist-dominant country, military expansion and human rights abuses committed by Myanmar’s security forces long pre-date the coup.

In the North, state violence is part of everyday life, even more so after war broke out again in 2011, ending the 17-year bilateral ceasefire agreement between the Myanmar Military and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). The KIA is the armed wing of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), one of the strongest among more than a dozen ethnic armed organizations fighting for political equality and self-determination.

Amidst this struggle for political agency, the Myanmar military has unleashed violence on the Kachin people because of our identity, with cases of arbitrary detention, killing, torture, and gender-based sexual violence, including rape.

As a Kachin human rights activist, I carry deep within me the pain and trauma of my community’s collective experience at the hands of the Myanmar military. Every time I speak to a survivor of sexual violence, or sit down with a man arbitrarily detained and tortured for simply being Kachin, under suspicion of being a KIA member, the way our people are dehumanized forces me to recall dozens of others I have met along the way who await justice.

But for many Bamar Buddhists, especially those from major urban centers, this raw state violence is a new experience. As the majority population in Burma, many have been in a state of shock since the coup. After the military annulled the 2020 election results, arresting Aung San Suu Kyi and leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) and blocking the new parliament, Bamar Buddhists feel their political rights have been robbed. And they are bewildered by the security forces’ brutality against peaceful citizens.

Before the coup, our calls for a stop to human rights abuses and direct support for humanitarian assistance to those displaced by the armed conflict were met with skepticism by the Bamar Buddhist population in urban centers. They assumed we were treated badly because we supported or were members of the KIA, who they believed were terrorists trying to break up the union. The military, on the other hand, was perceived as the protector of the union. Hence, the majority population saw the grievances of the Kachin and other ethnic communities as untruthful, and some even felt their suffering was deserved.

Recognition of Kachin’s traditional rights to land in accordance with our customs remains absent. Centralized national laws drafted in Naypyitaw, the secretive official capital and military headquarters of Myanmar, have allowed businesses with resources and connections to grab lands in the far north, pushing people out of their ancestral territories.

Resource-rich Kachin state, with various types of valuable minerals—jade, gold, amber, and timber—produces billions of dollars every year for the central government and military-connected crony capitalists. Global Witness, an environmental watchdog group, reported that 2014 jade sales alone were over 30 billion dollars, nearly half of the country’s GDP. Yet, the Kachin people have not enjoyed the benefit of it—a classic resource curse.

This protracted intergenerational displacement by armed conflict and land confiscation has come at a heavy cost for my community. We are physically and psychologically disconnected from our land. Our farmers have lost their livelihoods. Kachin youth are trapped by drug addictions as a way to escape everyday violence and fear.

This marginalization of ethnic communities in Myanmar has been amplified by international actors, who after 2012 placed blind faith in Aung San Suu Kyi, then seen as a darling of democracy, and poured the vast majority of resources into accelerating the national government’s centralization efforts, despite the fact that the military remained the most powerful decision-making force in the country.

The international community reasoned that job creation and development would keep ethnic communities happy and away from engaging in armed struggle, even though state-backed development schemes have always resulted in land confiscation as well as human rights abuses committed by security forces who come along to “protect” investment projects.

In prioritizing relationships with the generals, Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD missed the opportunity to create space for trust-building with leaders of ethnic communities and failed to recognize the grievances felt by civilians in conflict areas. This was demonstrated notably in the party’s decision to defend the military at The Hague against charges of genocide of the Rohingya community in Rakhine state.

*

Given this history of subjugation for minority communities in Myanmar, as tragic as the coup of February 1 has been, there is a silver lining. People from all walks of life, across ethnic and religious lines, have for the first time in more than three decades come together against the military regime.

On February 18, youth protesters from multiethnic communities marched together under the banner of the General Strikes Committee for Nationalities (GSCN), raising our respective flags high and proud on the streets of Yangon. Bystanders clapped their hands, welcoming us. Many raised the three finger salute that has become the symbol of opposition to the military coup.

I have lived in this city on and off for the last 20 years, but I have always felt like a stranger. Before the coup, ethnic activists were arrested and jailed if they tried organizing events to mark important political events. It was different this time. I tried to hold back my tears of mixed emotions; happiness and joy for being accepted as I waved my own flag in central Yangon; sadness and disappointment at the fact that it took a coup and many deaths for Bamar people to accept us.

In the months since the coup there has been a notable shift in understanding the plight of ethnic people and the way the Buddhist majority views ethnic armed struggle. A seller in my local wet market, sensing I was from a non-Bamar ethnic community due to my accent when I spoke Burmese, told me: “In my entire life, I thought those soldiers in uniform were protecting us and safeguarding the Union. Because we believed in those lies, we ignored what they were doing to the ethnic communities across the country. We were so wrong and ignorant.” Now, the Bamar population has seen the military’s true colors. In fact, in the last few months, thousands of activists, politicians, and those from the civil disobedience movement have fled to the liberated borderlands controlled by ethnic armed organizations for safety.

While the Myanmar military conducted vicious attacks on other ethnic and religious communities, including the Rohingya, it also successfully used the Bamar ethnicity and Buddhism as a basis for recruitment and expansion. For many Bamar Buddhists, atrocities committed by the military in ethnic areas have long been justified or excused by the fact that the military builds Buddhist pagodas in occupied areas and renames local streets and landmarks with historic burmese names. Consequently, Bamar Buddhists have enjoyed privileges associated with that ethnicity and religion. Meanwhile, Kachin and others have been penalized for our beliefs and language.

As a child, I had to sit through Buddhist chants in the classroom before school lessons in the Burmese language began. When my Catholic church tried to run Kachin language programs during summer holidays, the Church had to seek permission from the government, which wasn’t always successful. In contrast to this, Bamar beliefs and culture were promoted and celebrated widely above all others, designating a special and national status. The Bamar Buddhist citizens will need to recognize and acknowledge the privilege they have enjoyed collectively in order to truly confront how they may have contributed to strengthening the military’s institutional identity.

Since February 1, it has been heartwarming to see Bamar Buddhists’ feelings of regret and a new sense of understanding and empathy for what other communities have gone through. But how long will that last? Reconstruction requires a more resilient and deeper reimagining of new political and structural change where all people see and treat each other as equals while recognizing differences in our lived experience that some have had worse than others.

As we call for the immediate release of political prisoners and detainees, returning to the same political status quo constructed by the Myanmar military will be a betrayal to many lives, including Khukhu’s, who fought her entire life for equality.

This is the reason why I recently joined the National Unity Government, a body composed of elected NLD MPs and those of us nominated by our respective communities in opposition to the coup, not only to push the military out of politics once and for all but to seize this historical opportunity to help reconstruct a new and inclusive political system. I see it as an extension of my activism. I know this isn’t going to be easy but the effort will be worthwhile. We must make use of this important moment to build a political system that accommodates and celebrates diversity.

Federal democracy has never been more popular in Myanmar and getting it right this time will depend on recognizing concerns and grievances—past and present—from all of the country’s people. If we can do this, we stand a chance at paving the way toward a shared future, once and for all.