Photo by Masrat Zahra.

Photo by Masrat Zahra.

Anuradha Bhasin is a journalist with three decades of experience covering Jammu and Kashmir, with a special focus on border issues, conflict, and human rights. In her pursuit of justice she has occupied many roles, from organizing protest marches to participating in regional dialogues; she is both comfortable wearing “different hats” and always an activist. Bhasin is Executive Editor of the Kashmir Times, the oldest English daily in Jammu and Kashmir. She spoke with Ather Zia and Nimmi Gowrinathan about her political awakening, challenging the Indian Supreme Court over Kashmir’s communication lockdown, and the political strategies of women under siege.

Ather Zia: It was in the late 1990s when I first met you at different conferences, and by then I already knew your work. Everyone has several pioneering icons, and for me, you were one of them. Could you give us an overview of your background and your positionality as a woman from the region, as a political analyst, a journalist, and a writer?

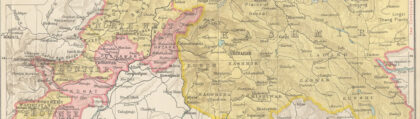

Anuradha Bhasin: As a child, I was fascinated by the borders [in the region]. The stories I heard from people around me, of people who had been impacted—these fascinated me. As I grew as a history student, I was drawn to study the conflict. And then there were the human rights violations, which impacted me as a human being.

I have often felt when you’re living in situations like this that it’s very difficult to draw a line between your professionalism and your activism. When you are here, living it, I think you have no choice. The question was how could I contribute while maintaining my professionalism? I could write about subjects by being as professional as possible and also highlighting marginalized voices talking about what was wrong with the system: corruption, brutality, and how it all impacted lives.

I felt that as an individual I could play a role. Activists come from many fields. I don’t see anything wrong with the journalist putting on different hats.

Nimmi Gowrinathan: I think that particularly for younger people, it is informative to hear how your own political consciousness evolved: what the key moments were for you, while also understanding that our political identities are constantly evolving. Was it when the guns showed up? Do you remember your father, the founder of the Kashmir Times, being harassed? When did your own politics form in relation to the world around you?

Anuradha Bhasin: I was still in school when my father was attacked in ’83 by the RSS [Hindu supremacists]. It was a murderous attack. They used knives and threw typewriters at him. I was conscious of the violence.

Jammu, where I live, suddenly saw divisions followed by a lot of polarization between the Hindus and the Sikhs in ’84. The arson, the fires, were our first signs of communalism. I grew up in a very liberal atmosphere. When we heard stories of the partition in 1947, we thought these to be relics from the past. We thought they were folklore, moments that had passed. And then they attacked my father.

By 1986, I went to college and started studying history as a subject. I was at Delhi University, which is a politically charged space and where my initial inquisitiveness about politics began. I began to understand that politics is not just about those in power; it is linked to day-to-day lives of people, expressions of views, and those early questionings of justice.

I wondered if men ever thought of acting as shields between the women and the security forces.

Nimmi Gowrinathan: You’ve mentioned stories that are not visible. Some of your work focuses on the stories of women in Kashmir. There is, first, the question of women being invisible in public discourse, but perhaps a more important question is: How do we see women in the entirety of their political complexity? How do you tell the story of human rights violations happening, and those that are gendered, without casting women as victims void of political perspectives?

Anuradha Bhasin: When I was a young journalist, I wondered how these kinds of violations could take place. Were they constitutionally mandated? No. Did they look like a part of any liberal democracy? No.

Inside this, many women’s stories had been missing for years. Women were part of the stories more as props. When the armed conflict began, they participated in the militant resistance more as supportive family members, less as equal partners. But they’ve been visible, they were part of protests, they have acted as shields for men.

There were women being raped. I wondered if men ever thought of acting as shields between the women and the security forces. Or did they think it was too dangerous for them? How is it that the women thought of acting as shields even when they were putting their lives there, their bodies there to be violated?

Our understanding of gender and the different articulations of inequalities evolve and deepen gradually. It was important also to look at not just the presence of women, but what exactly they were doing. A lot of the first women known as resistors in Kashmir were part of the group called the APDP, the Association of Parents for Disappeared Persons. It’s led by a woman named Parveena Ahangar, who co-founded it. Most of its members are women and they were and are doing tremendous work.

Ather Zia: In my new book, Resisting Disappearance: Women’s Activism and Military Occupation, I do illustrate early moments of the APDP struggle, when the activists underline that they are the victims and sufferers and theirs is an apolitical organization. When Parveena Ahangar speaks now, when the activists speak, they take a very, very strong political position, but also without foregrounding it as “political.” Their strategy manifests a politics of mourning, and it is remarkable how effective their work has been.

Anuradha Bhasin: Yes. They are talking about justice to know the truth about what happened to the men who disappeared in their families: their husbands, their fathers, brothers, and sons. But the stance they take, to say, “we don’t want your compensation, we want to know the truth,” is an extremely political position in pursuit of justice.

And I think these were ordinary women. Parveena Ahanger, the leader, is not a formally educated woman. She speaks in broken Urdu. But they created a niche for themselves in the way they think, so conscious of politics around them, and the way they participate publicly.

I’m trying to understand what it means. Is it something that they did consciously? Or is it something that they couldn’t articulate? Is it because in a deeply patriarchal society, there has to be a covert politics? Did they feel that they needed legitimacy with this kind of articulation of victimhood first?

Nimmi Gowrinathan: For the women more overtly engaged in visible politics—those who were involved in militancy, for example—do you know what some of their motivations for joining were?

Anuradha Bhasin: We haven’t had, so far, women joining militancy as such, as suicide bombers or women who pick up guns. We’ve had all along, however, women who acted as informers, couriers, and other forms of support. I met a few of them in Rajouri, Poonch mainly. Out of all the regions in Jammu and Kashmir that is the most conservative part, where women are reduced to an audience or they just don’t exist. That is the dominant perception, that women don’t have any agency in these regions. But one woman I spoke to had been working for the security forces and she earlier worked for militants. She had been a double-agent; that’s how she operated.

She would tell me, “I was always confined to the four walls of the kitchen in my own house. And my good-for-nothing husband used to rule over me.” There is so much we miss about women who are asserting themselves in ways we don’t see.

Ather Zia: In your work as a journalist and storyteller, you’re taking the legacy of your father, Ved Bhasin, forward. He is an inspirational figure for Kashmiris; he was not only an ally, but had no hesitation in saying, “I’m part of the struggle.” Can you tell us something more about his work and yours as well, in light of his legacy?

Anuradha Bhasin: Initially, my father wanted to start his newspaper in Srinagar, but it was not possible because the state made conditions to publish more stringent for him. For instance, to get a newspaper registered in those days, you needed to pay nominal charges, but for him the conditions were to pay 2000 rupees, which was a lot in the 1950s. So he was forced to move to Jammu. He initially got the Kashmir Times registered in someone else’s name, his friend’s father’s name. It was a weekly and the first copies had to be published in Delhi. Then from Delhi my father had to bring the copies by road. On top of this, his copies were seized because of the extreme surveillance that was prevalent in the 1950s.

Since the militancy, of course, and during my tenure, the journalists have been walking the razor’s edge and have been caught between the crossfire of many guns. Despite the fear, our bureau staff often had to use the art of diplomacy to convince them of the value of independent media.

Army men would barge into offices and demand that the handouts be carried like this. Then there was also this whole war on terminology. Do you call a militant a militant or do you say a terrorist? In the 90s, a term like “foreign militants” was suddenly used by journalists.

The initial word used was “guest militants” from places like Afghanistan because that’s how the militant organizations, the local ones, introduced them. The army objected, saying, “No, you call them mercenaries, foreign mercenaries.” So even here, how do you find a balance? Journalists have been trying to outsmart the guns on every side.

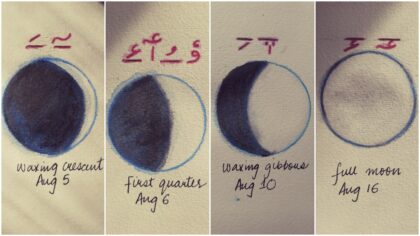

Ather Zia: After August 5, 2019, when Kashmir was put under a complete curfew and communication lockdown, you went to the Indian Supreme Court and challenged the state’s efforts to cut off the region. Can you give us the details of the case and the circumstances around it?

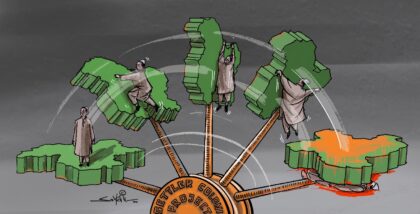

Anuradha Bhasin: Before August 5, the press in Kashmir has faced challenges, but this was unprecedented. I mean, seven million people in Kashmir, another three million from Rajouri, Poonch, Doda; ten million out of 14 million people made invisible.

I had no contact with my reporters. I wasn’t even sure what was happening. No one knew, initially. Every night from my house we would hear aircraft sorties. We would worry whether they were going to bombard Kashmir. My first thinking was, they’re going to do air strikes the Sri Lankan way. Because a lot of experts, like the military think tanks in Delhi, for years had been talking about this Sri Lankan [scorched earth] model [from 2009]. That was my worry.

And when there was absolute silence—you don’t know about what is happening, no phones are working—you worry because you know the history of Kashmir. You say, “Okay, there will be lots and lots of disappearances or people butchered and killed.” I heard that there were many arrests. The three former chief ministers have been arrested, so who else is safe? And these are the three chief ministers who’ve been so pro-India, virtually prophets of India. So, I wasn’t sure if my staff was safe either. And I had no choice. I had been talking to my lawyer friend Vrinda Grover and on August 10 I filed a case in the Supreme Court of India to challenge the internet and communication lockdown.

On August 17, for the first time, I heard my bureau chief’s voice. He was calling from the media facilitation center that was set up by the government for the media and it was under complete surveillance. My bureau chief and I have been working together since 1991 but I had never heard such fear in his voice. He just wouldn’t speak. After a couple of calls I realized that their numbers and details were being noted as well as those of whom they were calling.

I wasn’t very optimistic about what would happen because Indian courts even before August 5 have treated Kashmir very differently. Yet there were no other options. The Supreme Court was busy dealing with the Ayodhya hearing which also would affect our case. I had no expectations from the court, the way they were and have been behaving with the habeas corpus petitions and everything. It took the court six months to decide.

In January 2020, the Indian Supreme Court gave the verdict that the internet is a fundamental right. Of course, the judgment was significant, but essentially the government has gotten away with not implementing what the court had said in spirit. On top of only having the slow 2G internet service restored, every now and then a situation develops in Kashmir which the government uses as an excuse to shut down the internet, to shut down mobile phones, sometimes for a week, sometimes just for a few days. It has become a routine practice.

The surreal is very real now. In fact, we’ve gone beyond that.

Nimmi Gowrinathan: Is there a story that has stayed with you that shows us something about the intimate impact of these layers of violence on people’s lives and choices on the inside?

Anuradha Bhasin: There was this one woman who talked about the threats she faced in her village, a hilly, sparsely populated area. Houses were two kilometers apart. If you are not living in clusters, insecurity presents itself very easily.

She was threatened by some local militants who had some scores to settle, and on the other side by an army man—really related to their own dispute. So, she became a village defense committee member and picked up a gun. “I used to sit on this bed,” she told me. “My children were very young and all night I wouldn’t sleep and be holding the gun.”

I was trying to imagine this woman sitting there in the bed in the middle of a big room and the children sleeping on both sides of her, what she was thinking. That gun helped her to also earn some respect within her own village and resolve certain disputes.

Now, regarding the gun, I did a lot of work in 2018 in the field in Kashmir. And I could see a whole difference in the approach of the younger women, college and university students, and women of the previous generation. In 2018, protests erupted in the valley. There were women who started pelting stones for the first time. There were younger women who were saying, yes, we are ready to pick up the gun.

But there were two different versions I got from these youngsters who wanted to pick up the guns, these young women. One was: “We will pick up the gun when they allow us.” They mean the men. But there were some women saying: “We will decide when we want to do it.”

Nimmi Gowrinathan: Ather mentioned the influence of your father, as well as your writings on her own political thinking. Do you remember the early texts that resonated with you and helped illuminate the inequality and violence you were witnessing inside Kashmir?

Anuradha Bhasin: A bit of Karl Marx. I was trying to look at communism very critically because a lot of my friends were communist, and I could see the contradictions within what they believed in and what they practiced. Kafka. I was quite drawn to political fiction. I read a lot of George Orwell. I recently read 1984 about two years back again, because I thought it was important to re-read. Because in 1984, [when I first read it], it seemed like it was an impossible fiction. It was just so surreal. But the surreal is very real now. In fact, we’ve gone beyond that.