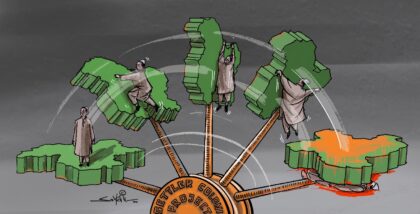

Illustration by Suhail Naqshbandi.

Illustration by Suhail Naqshbandi.

Close to midnight on August 4, 2019, police vehicles fitted with megaphones pierced a deathly silence in Srinagar, the capital city of Indian-controlled Kashmir. Officers tersely ordered residents to stay indoors or face “strict action.” This was not unusual for people subjected to frequent and punishing curfews and lockdowns every time they have seen reason to protest. But this instance came after a dizzying and confusing week.

I was reporting over the phone at that time, describing for a global newswire how Indian government forces had fanned across the city late at night, erecting barricades and laying a coiled maze of concertina wire across the main roads.

Suddenly, mobile internet services started going down, network by network, a tactic frequently used by authorities during times of unrest in the ever-restive disputed region. Soon, voice calling also went silent, with smartphones displaying “no service.” I switched to my neglected landline to report the intensifying tensions that had gripped the region for days, New Delhi having flown in tens of thousands of troops into what was already one of the world’s most militarized spots, with an estimated half a million Indian soldiers deployed.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of others—foreign and Indian tourists, migrant workers from India, and Hindu pilgrims who had embarked on the heavily guarded annual pilgrimage to the cave shrine of Lord Shiva in the Himalayas, all had been ordered to leave the territory. Many months before the coronavirus lockdown in March 2020 forced millions of migrant workers in Indian cities to walk hundreds of miles back to their village homes, some had experienced a similar shock in Kashmir. The numbers leaving the territory were unprecedented.

In a frenzy born out of a sense of despair and fear of what might lie ahead, residents stocked up on essentials. With everyone kept in the dark, the Kashmiri people were faced with the prospect of becoming what they have always imagined themselves to be: a besieged nation.

An isolated people suddenly pulled out from the global village promised by the internet.

A minute or so after I began reporting, the landline too went silent. Now, there was absolutely no way to relay information out of Kashmir. A total blackout and military siege was firmly imposed across the territory. People could not step out of their houses; I was stuck at my office and forced to sleep there for a few days. It was as though we were fish, electrocuted and then lying still in dark waters. An isolated people suddenly pulled out from the global village promised by the internet. The only window left open to the outside world was satellite TV, access to which is limited in the region.

There have been many military lockdowns over the last three decades. One winter morning in 2013, I woke up to news that Mohammad Afzal Guru, a former Kashmiri militant controversially convicted for his role in the case of the 2001 attack on India’s parliament, had been secretly hanged (his family was not informed before the execution) and buried inside Tihar jail in Delhi. During the ensuing siege of the Muslim-majority part of the Indian-controlled territory that lasted weeks, just looking out one’s window brought threats and abuse from paramilitary soldiers on the streets below. The Hindu-dominated Jammu portion of the region remained largely unaffected at the time. But mercifully, unlike this time around, you could make calls from fixed line phones. If, that is, you had access to one of the 50,000 connections for the seven million residents of the besieged Kashmir valley.

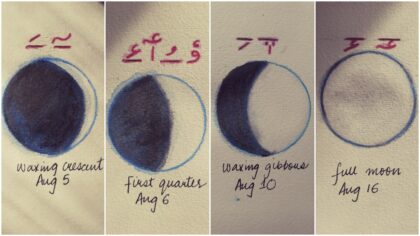

On August 5, 2019, everyone who could watched in shock as the Indian parliament struck a deathly blow to Kashmir’s political self, live across a dozen Indian TV news channels. The last remnants of the territory’s constitutional autonomy were thrown to the winds of history, even as most of the entire Indian-administered region’s citizens remained terrified, cooped up inside their homes, unable to find out what was happening across the street, in the next village, or with their loved ones elsewhere in the world. There was little space to think of responding to the political catastrophe.

*

In the preceding week, information emanating from Kashmir’s gargantuan security apparatus suggested that Indian soldiers had a license to massacre protesters if pushed. These rumors came against a backdrop in which Kashmir has been the site of large-scale civilian protests against Indian rule for decades. A brutal Indian response to Kashmiri political assertion—and an armed insurgency that is more than 30 years old—has created a landscape of unmarked and mass graves, disappeared young men, widows, half-widows (women whose husbands disappeared without a trace, with no means of knowing if they are alive or dead), orphans, and a silent epidemic of mental illness caused by violence.

A few days after that August night, once journalists could gingerly move around Srinagar, I walked the deserted streets of the city’s densely populated downtown. It had been transformed into an unfamiliar labyrinth, as if to make you forget the street map of your own city, the one you knew like the palm of your own hand. Doors and windows of homes shut, razor wire and barricades blocking roads, streets and alleyways manned by Indian paramilitary soldiers in bulletproof gear, wielding automatic guns and redirecting your walk in bizarre serpentine ways. It was impossible to follow the same route between any two points. To venture out was a punishment, for walking back meant a distance many times longer through the maze. If you stepped out of your home, it was as if you were caught inside a giant pinball machine.

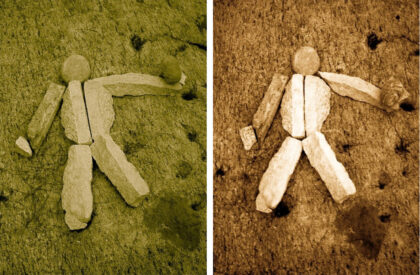

Residents who died during that siege, mostly the elderly and the sick, received lonely burials. Without the means to inform relatives and loved ones, only a few men from the family could be in attendance, just enough to dig a grave. This was a dispiriting experience, similar to what the world was to be introduced to some seasons later by the coronavirus pandemic, with individuals often dying alone, and funerals restricted.

Panic-stricken residents, mostly women young and old, started arriving at the city’s main hospital after grueling journeys often undertaken on foot. Doctors said most of them were clinically fit but experienced unexplained aches and pains and frozen muscles. I saw one young woman, whose legs had suddenly started disobeying her, lying almost lifeless on a bed in the hospital emergency hold, eyes wide open but fixed on the ceiling. A doctor on duty told me clinical tests run on her were all normal and that she was perhaps suffering “extreme emotional trauma.” The rest of the 1400-bed hospital was nearly empty.

In the days leading up to August 5, most patients, including those critically ill with serious diseases like cancer or organ dysfunction, had been sent home without explanation, where many of them later died for want of urgent medical attention. Medical authorities in Kashmir usually do that ahead of the Muslim festival of Eid, to allow some of the patients to celebrate with their families. Only this time, it was done to free up beds in anticipation of a rush of injured protesters.

Police had already locked away all prominent Kashmiri voices, even those that supported Indian rule over the territory. Thousands of others had been rounded up, and many of them, including children, were sent by nightly flights in military aircraft to crowded prisons in several northern Indian cities. Jails inside Kashmir had run out of space.

There were no protests in the expected places, like the city’s old quarters, and little way of knowing if protests were happening in the more remote, cut-off areas. Journalists would sometimes find out days after that isolated anti-India protests had taken place all across the Kashmir valley. The newly established Kashmir Press Club in Srinagar became a hub for reporters for exchanging information from areas they were able to visit. It took days for news and details of an iconic protest that had started on the first day of the siege in Soura, just six miles north of the city center, to reach the club. That protest continued for weeks as thousands of residents used every object available to barricade their area and keep soldiers from taking over their streets.

Protesters battered by government forces, fired upon with pellet-guns, many with hundreds of metal pellets lodged in their eyes and bodies, meticulously avoided reporting to hospitals, fearing arrest by police.

*

Some weeks later, in the moment many in Kashmir have started likening to the Palestinian Nakba of 1948 and China’s ethnic flooding of Tibet, I ventured into the rural hinterlands, on completely deserted roads meandering through apple orchards and paddy fields. It felt as if some apocalyptic event had sucked out the people from the vast and beautiful landscape of the Himalayan valley. But inside rural homes, I encountered angry, fearful, and psychologically devastated communities.

These were the ways a complete silence was militarily implemented across the territory and people were forced to swallow the heist of their exclusive homeland rights.

In village after village, residents narrated harrowing stories of what was done to them from the night of August 4 onward, after the total communication blackout was firmly put in place. Indian soldiers from the hundreds of camps that dot the rural landscape of Kashmir had repeatedly descended into villages, raiding and vandalizing homes, smashing cars, and destroying stocks of rice and pulses (sometimes even mixing in kerosene). Villagers told of how in the dead of the night young men were tortured on the roads and inside army camps, after soldiers had confiscated their smartphones.

Frightened villagers corroborated each others’ tales of torture and narrated instances of how their shrieks were broadcast over loudspeakers to terrorize entire neighborhoods. They described how soldiers would routinely ask young men to report to their camps to collect back their phones, which at the time were nothing more than devices used to record evidence of the horrors inflicted upon them. To report to the camp then was to almost volunteer for abuse and torture. If their smartphones were returned, it was only after all incriminating video had been deleted.

These tortured young men were made into examples across clusters of villages to deter even the thought of protesting. One young man said soldiers snatched him from his home, tortured him throughout the night, and forced him to drink water from a pit where the army camp’s toilet drain emptied out. He passed out, and before his family was allowed to carry him home the next morning, he was also threatened and ordered not to visit a doctor or share his horror with anyone. Another, who invited me inside his home and spoke over his lunch, said he had been so terribly beaten with guns and rods by soldiers that he wasn’t able to leave his bed for weeks. An ambulance driver told me how soldiers prevented him from taking six battered men to hospital.

These were the ways a complete silence was militarily implemented across the territory and people were forced to swallow the heist of their exclusive homeland rights that the abrogated Article 370 of Indian Constitution protected. This was the nature of the “peace” that was amplified in the largest sections of the Indian mainstream media by officials both in Srinagar and New Delhi.

*

How long would it have taken Indian strategists to think up and plan the meticulous lockdown and military siege of Kashmir? With this question in mind, I tracked the utterances of many key Indian politicians and ministers in the Narendra Modi-led government, looking for clues.

In February 2019, a young militant Kashmiri had blown himself up a few miles outside Srinagar when he rammed a car laden with explosives into a convoy of Indian paramilitary soldiers, killing at least 40 of them. New Delhi blamed the suicide attack on Islamabad and later launched airstrikes inside Pakistan. This brought the two nuclear-armed rivals to the brink of another war, but the quick return of a captured Indian fighter pilot during a dogfight with Pakistani jets over the skies of Kashmir helped the situation cool off.

In May 2019, in a national election that followed in the aftermath of the airstrike, the ruling BJP was able to hugely swing the electorate in its favor, and it brought Modi to power for the second consecutive term. Defense minister Rajnath Singh surprised everyone by promptly saying New Delhi could review its long held “no-first-use” doctrine of nuclear weapons. He also reiterated a 2017 declaration that a “permanent solution” to the dispute over Kashmir was being worked upon. There was a distinct smell of a third war with Pakistan over the disputed region of Kashmir.

A string of Indian laws that earlier needed approval from the elected local legislature have already been wantonly and unilaterally imposed on Kashmir.

But the developments after August 5 took me further back, to Modi’s second year in office. On a sunny day in November 2015, he declared in Srinagar: “I don’t need advice or analysis from anyone in this world on Kashmir.”

That day, he was only addressing a few thousand local Muslims bused into a heavily fortified cricket stadium by the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), New Delhi’s latest ally in the contested region. At that time, few took Modi’s pronouncement as anything more than an unsparing snub to the territory’s chief minister, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, the since-deceased leader of the PDP. Sayeed was perceived by many as the only Kashmiri who was “Indian by conviction.” He had also been the only Muslim “trusted” enough to serve as India’s home minister, where he had helped steer a brutal counterinsurgency military campaign in Kashmir in 1990 when a local armed rebellion had first shaken New Delhi. But now, Modi was showing this Kashmiri his place.

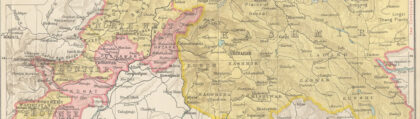

Modi has his roots in the Hindu supremacist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a paramilitary movement with millions of members across India, and the mothership of his BJP. From Srinagar, he had given the first major signal of what India under Modi had planned for the unyielding Kashmiri struggle for the right to self-determination. Although much of his speech was cloaked in the condescending language of economic development, for the people of Indian-controlled Kashmir the devastating consequences of Modi’s deceptive avowals were to unfold four years later, in August 2019, when India annexed the territory, bifurcated it into two “union territories” under direct rule of New Delhi, and snatched the exclusive Kashmiri right to their ecologically fragile Himalayan homeland and their natural resources.

Hindu-majority India has since rolled out a robust plan of demographic flooding, which many Kashmiris and others have described as the beginnings of settler colonialism in the Muslim-majority territory. Any Indian who has the money to buy land or meet the fairly easy criteria set by New Delhi for becoming a domicile in the disputed territory can now settle in Kashmir.

This is clearly aimed at changing the facts on the ground and drowning out the Kashmiri demand for self-determination mandated under existing United Nations resolutions. New Delhi had been unable to put down a popular Tehreek (movement) for decades, despite its immense coercive military apparatus, its violent propaganda, and the continuous disempowerment of Kashmiri citizens. The RSS, of which Modi is a lifelong member, has long advocated changing the Muslim-majority status of Kashmir as the “final solution” for neutralizing the region’s demand to restore its sovereignty. Now, it is being undertaken with little regard for Kashmiri sentiment or the region’s political history and rights.

In the months following the aggressive August push by New Delhi for a “final solution” to the seven decades-old dispute, the militarized administrative apparatus steadily subjected life in Kashmir to a punishing arbitrariness. A string of Indian laws that earlier needed approval from the elected local legislature have already been wantonly and unilaterally imposed on Kashmir, replacing existing ones.

Government contracts for mining and timber extraction from pine forests, earlier tightly controlled and restricted to permanent residents, are now open to Indian companies, with much-loosened environmental safeguards.

During the 1950s, when the territory enjoyed a good degree of political autonomy, Indian-controlled Kashmir implemented successful agrarian land reforms, called “Land to Tiller.” Apart from redistributing land among the landless, the liberating and far-reaching reform also put a freeze on holding more than ten acres by one person. Those safeguards are gone. Also, permanent residents have lost their rights to the use of state land (commons). That title now rests with New Delhi.

But among a handful of local laws retained is the Public Safety Act (PSA), originally legislated in 1978 for preventing illegal felling of forests and timber smuggling. This law, which allows authorities to repeatedly detain anyone for up to two years at a time without being charged or put on trial, has mostly been used to lock up hundreds of political dissenters and protesters during the last three decades. The local high court recently refused to free the president of Kashmir’s Bar Association incarcerated under PSA since August 2019, saying that he had not “shunned” separatist ideology.

Apart from regulating and reshaping the region’s political economy, the life of Kashmiris has also been constricted by hundreds of new checkpoints and bunkers that have sprung up across the extremely militarized territory.

The arbitrariness has percolated down to a policeman or soldier who can refuse to even accept a “movement pass” issued by civilian authorities. I recently spent an hour at a checkpoint in Srinagar when a policeman, from a group armed with automatic rifles, refused to let me pass. “These passes have been cancelled,” he said casually, advancing a spurious pretext to stop a journalist. It was of course not true. But there was nothing I could do except yield to his will or risk being detained, or worse, shot. A young man driving his police officer uncle to Srinagar’s Police Control Room was recently shot dead by paramilitaries at a checkpoint outside the city. For the average Kashmiri, these checkpoints have always been sites for humiliation and apartheid, but now, federal forces are exercising more power on the street than ever before.

*

Some of the lockdown restrictions, mainly those on communications and internet, had just begun to allow Kashmiri people something of a breather earlier this year, when the coronavirus pandemic brought another lockdown upon them. As residents worried about the spreading disease, the ferocity of India’s coercive political actions gathered pace. Now, while the world focuses on handling the public health and economic crisis, the pandemic is being used by New Delhi to fuel a Hindu supremacist ideological project in the territory. Drastic changes have been implemented, deeply disempowering for the Kashmiri people already emaciated from nearly a year of multiple lockdowns and with no way to respond or protest.

Inside Muslim-majority Kashmir, reportedly doubtful practices produced inflated data about coronavirus infections, secretly helping to construct yet another alibi for continuing the lockdown. This intensified paranoia about the raging virus among the people as they are being subjected to sweeping, historical changes without their participation or consent.

For the moment, unable to fathom the pace of the sweeping historical changes being foisted on them, the isolated people of Kashmir appear caught in a wilderness between numbness and a silent rage.

In May 2020 the counterinsurgency war that has been raging in the rural areas for three decades returned to Srinagar after a long gap. At least 15 homes were destroyed by government forces who fought and killed two armed rebels in the heart of the city’s old quarters. Like many such earlier incidents, their bodies were not returned to their families for last rites, and police instead buried them some 50 to 60 miles away in uninhabited border areas. The pandemic had afforded the military apparatus another pretense for punishing the slain rebels’ families.

I recently encountered a family of a slain rebel in the remote Sonamarg area, close to where his body was interred. Exhausted from walking miles amid a double lockdown, their eyes were red from weeping and sunken from grief.

“We just prayed and marked my brother’s grave. Please don’t ask anything,” a young woman clad in a black burqa said, and continued to walk with others.

Amidst the coronavirus lockdown, the Indian government also issued new “domicile rules.” These rules do not just make it possible for Indians to easily acquire citizenship rights in the former State of Jammu & Kashmir, but also forces its permanent residents to surrender their “state subject” certificates in order to secure a new domicile status. This was no less than a project of erasing a history of Kashmiri citizenship, for the state subject certificates have been issued to residents for nearly a century, a sort of passport enshrining homeland rights long before India and Pakistan had emerged as independent states ending British rule over the subcontinent in 1947.

Now, an alien bureaucracy, supported by powerless Kashmiri civil servants who have been reduced to rubber stamps, seems to be implementing orders from New Delhi, totally dismissive of local sentiment, bereft of sensitivity to civil rights and political morality, and determined to dismantle the ethos and erase the history of the territory. It has already announced “land banks” to be offered to Indian investors, eventually intended to become settler colonies in a place where the Indian army already occupies thousands of acres of fertile land and has a huge appetite for more.

For the moment, unable to fathom the pace of the sweeping historical changes being foisted on them, the isolated people of Kashmir appear caught in a wilderness between numbness and a silent rage.