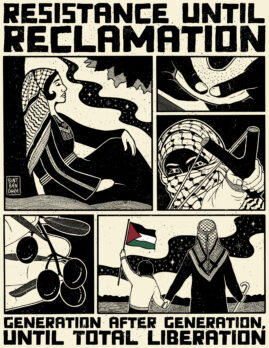

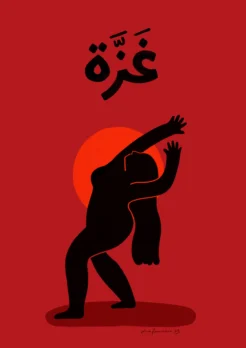

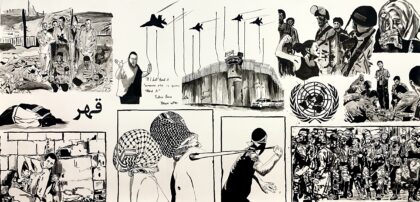

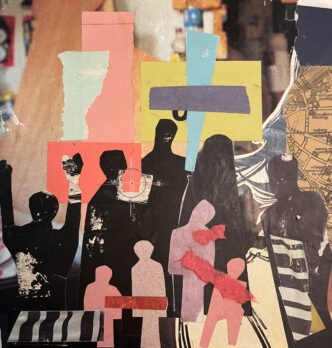

Artwork by Dina Fawakhiri

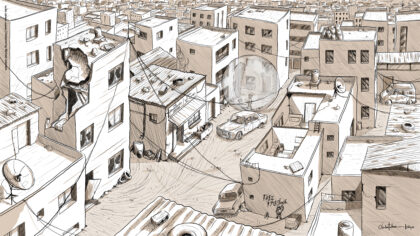

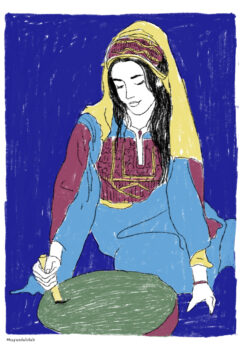

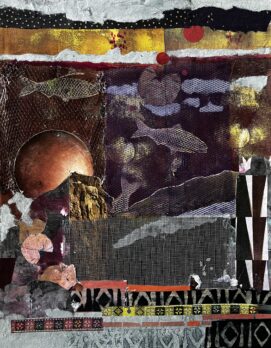

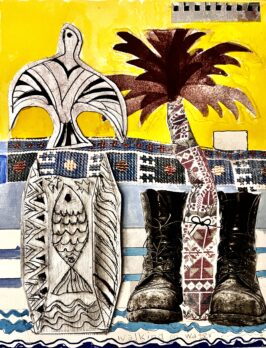

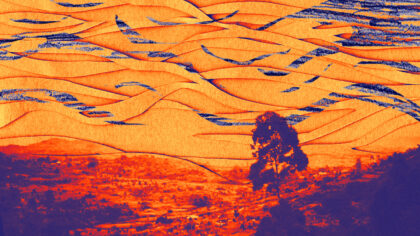

Artwork by Dina Fawakhiri

Location: I live on Confederate Villages of Lisjan territory in Oakland, California.

On Trans Day of Visibility last year, I posted a photo of myself after top surgery, and commented on what it means to be trans. My jiddo responded, “We see you and love you as you are.” He understands, in a way few can, the necessity for affirmation of one’s existence.

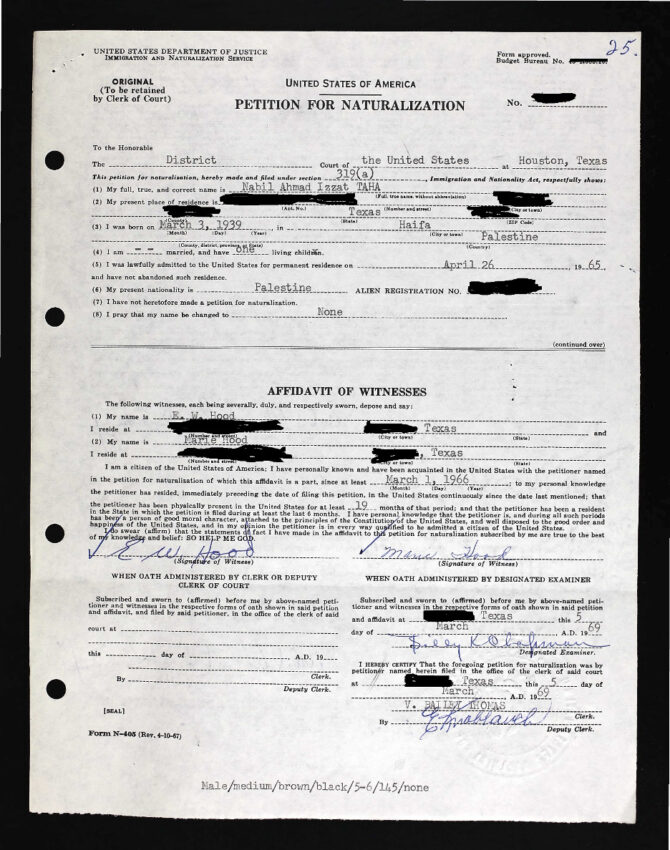

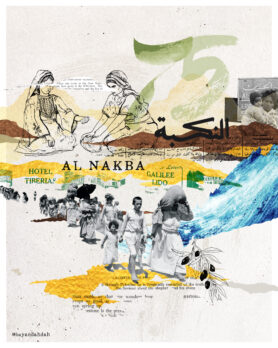

My jiddo’s name is Nabil Ahmed Izzat Tahha. In 1948, at the age of 7, he witnessed neighbors in Haifa, Palestine lying naked and dead in the streets, and children “going crazy” over the loss of their families. Luckily, he, along with his parents and six siblings, was able to escape to Sur, Lebanon.

My great grandmother, Badrieh Al Khamra sold her jewelry to keep everyone fed. This kept my family alive for a while, but after five months, all of it was gone, and the food along with it. Their arduous journey took them to Syria and, eventually, the United States.

In 1959, my jiddo was accepted into Purdue University with less than $20 to his name. He took a job as a dishwasher making $0.80/hour to pay for school and living expenses. Then, in 1964 while at a church event to get some food, my Muslim Palestinian jiddo met my grandmother: Sharon Elizabeth Hood, a young, white Baptist, small-town girl from Texas. Not long after that, on February 24, 1965, my mom, Rhoda Nabil Taha Makled, was born in Baytown, Texas.

Despite long odds and unrelenting racist encounters, and through hard work and education, my jiddo was able to make a life and raise a family here and eventually attain citizenship.

To colonizing propagandists, our story is the American Dream. To us, it’s an ongoing tragedy. Every few years, when Palestine reenters the news cycle, we are forced to relive the trauma our family went through, feeling deeply the continued suffering of those living in our homeland. Israel’s current, blatant slaughtering of Palestinians has only made my jiddo’s recurring night terrors worse.

In my mother’s words, “In a world where colonization still draws painful borders around indigenous lives, through silent echoes of the past and loud clamors of the present, the narrative of my dad’s shattered dream and unyielding survival stands as a testament. It is a soul-stirring reminder of the human spirit’s unyielding flame, burning fiercely amidst the chilling winds of conquest, illuminating the paths of resistance for generations to come.”

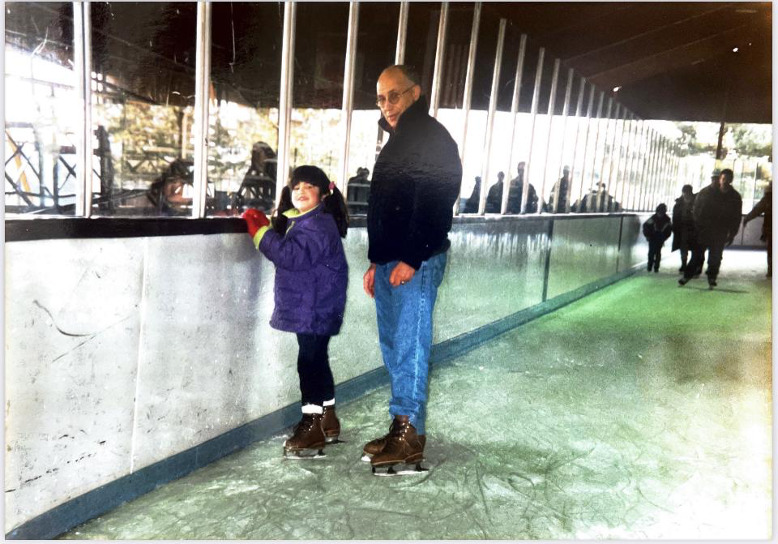

The trauma of genocide will continue to be felt in our bodies for generations, but so will our beauty and resilience. It’s part of what’s given me the strength to be openly trans, and my family to support and love me unconditionally.

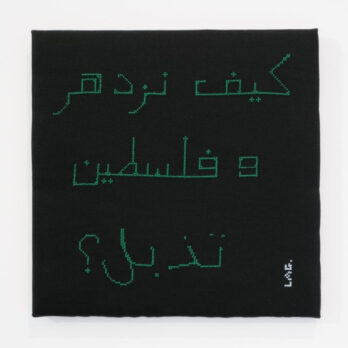

“We [Palestinians] are not going away. We’re in this world to stay, and the world is going to have to deal with us.” – Jiddo