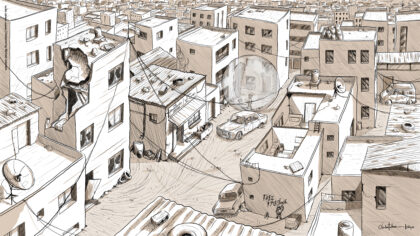

Splashes of youthful green, white, and red adorned the ancient corridors of my Gaza. Maghrib Athan reverberated against concrete walls, as sizzling shawarma shops sang, a chorus of clattering pans and kitchen screams. Their sounds, a soothing hum, soared as my best friends, Ahmad and Mohammad, joined me, as we maneuvered past donkey carriages and Amto Hana’s yelling. Her fogged up glasses obscured her vision, allowing us the perfect chance to escape her grasp. Scents of bakhoor and apple argeeleh led us past the cramped housing districts. Eventually, as dilapidated properties leave way for wide, open expanses, we were met with rubbled homes. Ummi and Baba’s warnings come to mind. They weren’t safe, but I wasn’t convinced. Skipping past plains of charred cement, we were blinded by adrenaline, high from it. Our eyes zeroed in on any signs of forgotten treasure. Sieving through the remnants of a kitchen, throwing shattered pots and pans to the wayside, a glimpse of gold caught my eye. Pushing Ahmad aside with a quick shove, I plunged my hand into the rubble. But when I pulled it out, Allah reminded me of where I was. In my hands lay strands of human hair.

Gazan skies were always gray. Beneath the sky were the claustrophobic alleyways that stunk of feces and desperation. I used to sit in corners burning incense and splashing on perfume to mask it. When supplies ran low, I substituted with olive oil, a flask never left my side.

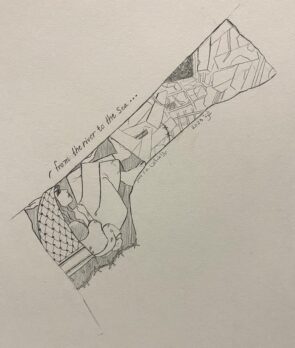

My first love, the sea, was ruined in Gaza. I despised sitting by the coast where fishermen softly whimpered at the nonexistent catches. The good patches were always out of grasp; Israeli guns kept us away. I detested locking eyes with the soldiers; even now, their scowls are burned into my memory. The same look Baba gave when a beetle under his thumb crawled away, refusing to die.

Amo Adnan’s pale, grayish-blue body was the first time I had ever seen a dead body. His death was dressed in rose petals, olive branches, and prayers. A futile attempt to hide the crimson holes that dotted his body. Terror struck me that night. I hyperventilated until I was a sickly purple. Tears drowned out my screams for help.

My capacity for sorrow gradually rotted away. Future funerals would be met with blank stares. With every loss, a numbness strengthened its hold on my soul. It was a comforting presence. A haze was slowly engulfing my mind. It felt like a superpower. Loss could not stir me anymore, my Gazan gift.

Flickering yellow candles dotted the alleyways as daily electrical outages gave way for night-time battles. Swarms of young boys fought make-shift duels in the streets; Ahmad always played dirty. By the end of the night, he would proudly show his black eye to his friends as a badge of honor, while I would go ice my wrists as Baba scolded me for the fifth time that day.

Days after my uncle’s funeral, our family arguments morphed into intense bouts of laughter. Hamzah and I waged eating contests against each other every few days; I would always win. We’d laugh so hard that it was hard to keep down the warak enab that we’d filled ourselves with. Our neighbors complained loudly several times. It was a moment of joy. Ummi was adept at easing the terror that reigned in our minds. Even while tears streamed down her face, she promised that our births were for the best. We would, eventually, thank Allah for our Palestinian blood.

I wonder if she still believed that when her brother was killed. She didn’t cry that day.

When hell reigned down from above, nothing was immune from the destruction. Not my mother’s gorgeous smile, which, since that day, has been a sight seldom seen. Not even the intricate churches and mosques that I would lie under in the daytime, soothed to sleep by the chorus of athan, church bells, and the click of donkey footsteps. Allah taunted me in the way that the shattered minarets twisted around with strewn body parts, leaving a sinister smile in the sand.

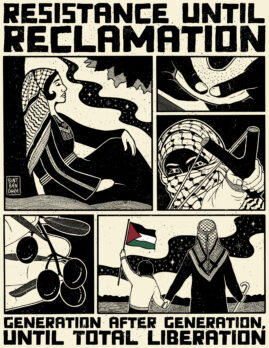

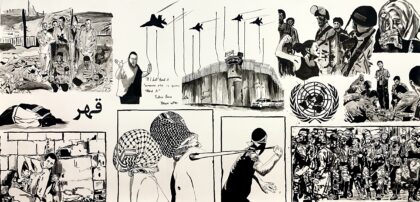

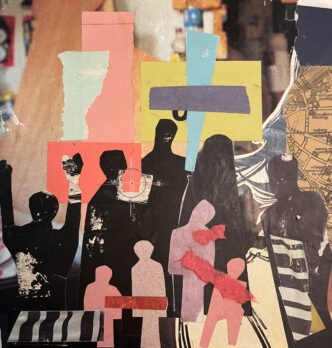

Warfare contorted our homes into walled enclosures. We were caged animals, desperate at any chance to break out. Many boys died in Gaza to prove they weren’t dead. To feel a taste of life, we grabbed stones – violence was the language that Palestinians are forced to speak.

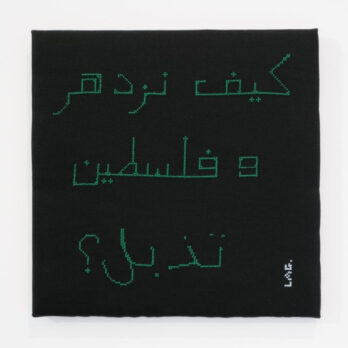

Occupied minds seek only to break free. Life in Gaza was akin to a suffocating purgatory; a slow chokehold that, eventually, took you. There is a kernel of truth to the saying: “Palestinians love death more than normal people love life.” Far from triumphant, it shows the extent to which the occupation, and the destruction and loss it has wrought, has corrupted perceptions of hope. All that is left are hollow husks striving for nothing more than an instance of life’s vitality. Anything to stir that dormant and longing soul.

On October 7th, another chapter in this tumultuous desperation began. As I saw the news rolling in, as the extent of the destruction and bloodshed became clearer, a familiar panic washed over me. I knew this would be the end of my past life, and I was powerless to do anything to stop it. Amto Hana, a shining force in my life, the one who gave me the courage to choose living, was thrown into Jannahem, as fiery bodies took the shape of missile fire and endless expanses of hellfire were seasoned with scorched concrete. Telegram became my obsession as the internet became unstable. I checked every few minutes for any sign of life from her. My stomach twisted every time she went offline. The cycle continues to this day.It’s been weeks since I’ve last heard from her.

Visions of Amto Hana: Late nights enjoying knafeh; the scent of cinnamon, nutmeg, and pistachio dancing in the sea breeze. Amto’s tendency to give a little dance before every bite, her cracked glasses evidence of her clumsiness from time to time. One of the few remaining lights in my life was dimmed by circumstances out of her control. I wish I could forget these moments. Even the tears I shed transport me back to the day I said goodbye to her in Gaza City on the day of my family’s escape.

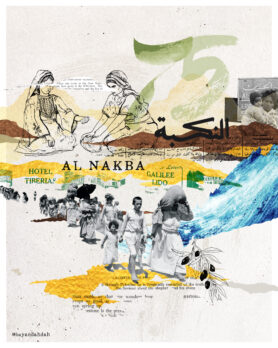

When we left Gaza in 2010 as the last stragglers on a plane headed to nowhere, it felt like my soul had lulled for the first time. My breathing eased and my constant twitching stopped. As home slowly disappeared from our view high above the clouds, an intense sadness washed over me. All I wanted to do in that moment was rush back into Amto Hana’s embrace, kiss her gently on the cheek while her soft laugh soothed me. My hatred for Gaza had evaporated. Memories of bodies lassoed in the fray and nights hiding from shrapnel rain faded along with it. All that was left was longing.

There are days where it’s difficult to believe these memories belong to me, a faux remnant of a past life. My time in Palestine is a hollow shell. I bear its name but have shed its soul. Hummus and falafel taste dull. Trips to the coast lack the vitality they once had. Real happiness is difficult. Any moments of childish elation are immediately tempered. Even reminiscing about prized memories, such as stealing dates from the local market alongside Abdullah and Mohammad, sting. All I can remember is the day I learned that Abdullah and his little brother had been killed. Visions of his father attempting to burp his dead baby still haunt me.

That night, Amto Hana spent hours combing through my drawings, excitedly complimenting me when it was clear she had no idea what was on the paper. It was the glint in her eyes that finally got me to stop crying. It was the cheery way she described my drawn dog as a turtle that saved me from weeks of anguish.

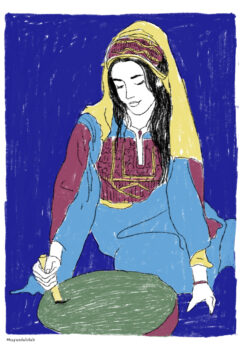

It feels like I’ve been spending my life attempting to recreate these pockets of Jannah. Gazan joy was sweeter. Smiles felt different, our chuckles had a distinct flavor. Never was there a sight more beautiful than Teta’s toothy smile as she rolled malfoof on her patio amidst her pomegranate trees. Laughter was never as powerful as the day she invited a few too many stray kittens into her kitchen.

When I sit in the Mississippi plains, surrounded by loblolly pines and sweetgums, it harkens me back to the olive tree fields of my childhood. Sedo’s booming voice echoes in the distance as he recounts tales of childhood hijinks, his gray beard shines with a radiant luster. As the light slowly fades from the clouded skies, I chase the Baladi chickens into their pens, weaving through the dips of the olive trees. Ummi never moves an inch during these moments. The gleam in her eyes as she marvels at her hero is my first taste of wonder.

Before planting each of those trees, Sedo would kiss the seed, imbuing with it a piece of his soul. Our family, as well as all other Palestinians, are forever ingrained in our homeland’s soil, no matter where we stray in the future. For years, I relished Ummi’s retellings of Sedo’s stories, always the first to sit down. Shai was brewed and sweetened with too many spoonfuls of sugar; scents of cardamom and thyme were tantalizing. Halloumi hotcakes hissed as crisp falafel bites came to life in their golden lakes. That cramped room in Ummi’s house in Gaza was my cathedral. The symphony of creaking floorboards, downstairs arguments, and wobbling window sills was its choir. Ummi’s soothing words were my call to prayer.

Palestinians are the parched earth of the Naqab desert. We are masters at thriving off abandonment. Allah bestowed upon us the unbelievable capacity for pain. And with as much tenacity as a caged lion, we hold on to the sputtering embers of hope and nurture them. Names of fallen loved ones constantly fade then re-emerge in memory. We keep waiting for justice. Loss is an ever-refreshing entity we can’t escape, so we manufacture our own slices of Jannah to spite it. The flipping of the stewpot in the dramatic reveal of the maqluba. Quiet night strolls near the fish market, as neighbors laugh and argue in the same breath. Tranquil moments sitting beside Teta as we lay out the molokhia to dry atop cotton beds while the idyllic hum of the motor fan drowns out our hushed whispers. Memories as sweet as the Egyptian mangoes Ummi would bring home in summertime.

A few months ago, deep in Amman, Jordan, I shared some of those mangoes with Amto Hana for the first time in decades. Her cheery smile and infectious laughter left me grinning for hours at night, long after everyone had fallen asleep. The way she would chuckle at my awful jokes reminded me of how beautiful humanity could be. A meeting decades in the making.

But she couldn’t stay forever. I am writing to keep her near.

Our tearful goodbyes transported me back to Eid visits in Khan Younis, where day-long excursions with Amto Hana were cut short by my dad’s endless yawning. Every farewell was followed up by trips to the local baker to acquire Taboon for night treats. The baker’s skills captivated me every time. The way the flour would float as he catapulted the bread into the air, weaving and twirling it at breakneck speeds. Then he smacked the dough against the sides of the oven, and a loud crack bellowed from its gaping abyss.

Baba once mentioned how Palestinians were the patient dough of the Taboon. No matter how much we are kneaded, beaten, and stretched beyond our limits, our capacity for hope is supernatural. Taboon, even burnt beyond recognition, is still Taboon.

Despite all that, it’s difficult to erase the bitterness of the burnt edges. My home has been devastated. Friends and family have been murdered. The future of Gaza is one rife with worry. Even if Amto Hana survives this ordeal, she will never be able to return home. It was destroyed early in the aggression. The haze that has engulfed Gazans is far stronger than anything caused by missile fire and debris. Those same hollow husks have seen their carcasses torn apart, as missing limbs inscribed with the names of their owners dot the landscape. I worry what this ignited desperation will create.

It’s only when I open Telegram that my worries ease, even for just a moment. I keep looking at photos of Amto Hana’s glowing smile. In one of the photos, she has barricaded herself in her daughter’s home as the chorus of missile fire edges ever closer. Even as she watched everything she holds dear blown to smithereens, eating scraps of bread to tide her hunger, she was comforting me thousands of miles away. It is a testament to our love, one that transcends the feeble reality of life and death. Our memories will never rot or expire. As she holds war’s hand with a warm embrace, I ask her to borrow my lips:

On October 28, at 1:35 PM, the last time I heard from her, she left me with this message:

“Fighting to live is not difficult, habibi. Life is about how elegantly you suffer. Allah knows best. If he didn’t, I wouldn’t have been born Palestinian.”