Illustration: Osheen Siva

Illustration: Osheen Siva

Manhattan

Do you ever think, you ask one night in October, walking through Chelsea, of how insignificant our lives are?

Autumn in New York. The nights are a boon. The dark air is light on our skins, and sound carries through the clear like ribbons.

A bar of yellow highlight cuts across my calendar next month: my friend N and I are going to Sri Lanka, right before the federal elections. She was determined to fly from Chennai into Palali Airport, recently reopened as Jaffna International Airport under new management. Imagine! We wouldn’t have to go to Colombo at all.

But with the journey fast approaching and all updates about the airport’s renewal limited to halting social media posts, we will likely instead have to fly through Bandaranaike International, and from there, take the rail north. I hate the train, sighs N. I think of embarking from Colombo at sunrise; I think of the small towns and pink stations that will blur past us; I think of arriving into the steel heat of Yaalpanam.

It is past midnight, and I feel the calluses at the base of your fingers against my palm.

I take this too far. I never know how to let a moment be. My spine stiffens, words are falling out of my mouth. I lurch into a tortured primer on politics in Sri Lanka. This is how a war ends, with false starts. There are still corpses of buses and carriages along highways and train tracks, and there are still hollowed-out houses standing gaunt on residential streets.

The numbers are incomprehensible, I say. But those lives were significant. Each person was significant, each one was significant to someone.

This isn’t what you were talking about, of course. In profile, I see your eyes widen a moment and I feel you catch your breath at being unexpectedly pulled out of context. We were talking about nothing in particular, and now, suddenly, we are talking about massacre.

After we die, you explain, and the people who knew us die, no one will remember us.

I still think you are wrong. I think of all the people I do not know and will never meet, whose memories and whose physical matter I carry in me. I think of Nishnaabeg political scientist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson writing about living through centuries of occupation under the Canadian state: kobade is a word we use to refer to our great-grandparents and our great-grandchildren. It means a link in a chain—a link in the chain between generations, between nations, between states of being, between individuals. […] It is a long kobade, cycling through time.

I think of the poet Karunakaran writing from the North of Sri Lanka, that in the taken towns there are more soldiers than people. That same place from which Nilanthan would later declare, after peace broke out: I am / the biggest merchant / of this roofless capital / I came to sing an elegy / for an era old and dead / I came to recite the epic / of an era newly born.

I keep all this to myself. I am spent, and I don’t really disagree, and anyway why must I make everything a competition.

Newark

Trespasser strike—and I imagine placards waving mid-air beside the train tracks.

I had fallen asleep on the train to Newark International. A sickly, heady sleep, with dreams coagulating in my throat, sour phantom phlegm. I had thought, while slipping into unconsciousness, that the train was moving strangely slowly. I’d swallowed down a wave of nausea and claustrophobia, and sleep fell over me, thick.

Just two days earlier, I had been in Jaffna. Sleep returns me there, transports me from these American bridges to the headiness and disembodiment of waiting in all that sun and across all those numbered highways for the Sri Lankan election.

War wisps through our everyday, tendrils of smoke.

When I wake, the train is still. My eyelids feel like sandbags, my bones feel like paper. We are a stop and a half away from the airport. The intercom periodically rumbles, staticky. The conductor is stringing together words that do little more than identify the already obvious: we are stopped.

The other passengers are making phone calls, rescheduling flights, telling jokes, rolling their luggage around. A peculiarly New York sensibility, this big town camaraderie simmering over deeper tensions. Fatigue is crusting at the corners of my lips.

30 minutes later, the intercom informs us that there has been a trespasser strike. The conductor doesn’t explain the words, just repeats it. Trespasser strike. The phrase floats around in the carriage’s clammy air, one passenger after another testing it on their tongues, trying to understand what this secret means. Trespasser—withdrawal of what labor? stoppage of what work?—strike.

The train hit someone. The train struck someone. To have been struck, someone must have been trespassing.

Parsing language feels like drowning.

Write a poem—I have been carrying around Jonah Mixon-Webster’s Stereo(TYPE) for weeks, from New York to Jaffna and now en route to Toronto, and have only made it to page four—that will keep you out the grave.

I make my flight.

Toronto

The weekend is a haze. I am burying myself in time, pretending I am not waiting for the news.

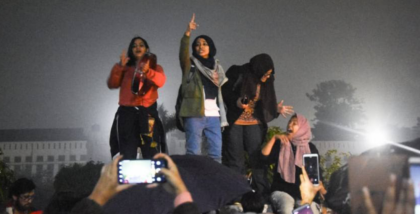

Late Saturday night finds me slouched against the wall of a dingy club, texting N. We are watching for the election results from Sri Lanka. The news comes in; the island has arrived at Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

A war criminal for president. As former defense minister, Gotabaya oversaw the height of wartime atrocities against Tamils. His brother and the country’s former president for that same period, Mahinda, will now be prime minister. A family business, this matter of genocide.

I would and should be afraid of what may come next, but my mind blanks. I was there just days ago. Why am I here, and how. The torture camps are not closed, the dead are not numbered. Where is the real. The music is terrible, and I am not entirely sober, drunk with exhaustion.

It is such a lot of death, I message you the following day, trying to explain why I feel shaken by these election results from another hemisphere. I am on a streetcar, which is how I know I’m not in New York. It’s like living life as double vision—one reality translucent and crookedly transposed onto the other.

What is death other than a commodity that people carry in their blood? asks novelist Youssef Fadel, from Morocco.

And from elsewhere in Morocco, writer and filmmaker Abdellah Taïa responds: I write from that death, and from all the times I died. It’s from there that I pronounce my own voice, and that I mix my voice with other voices, even with those voices that kill, that paralyze, that give the cold shoulder, that lie, that whisper or stay quiet. There is such violence within me and around me that I have no other choice but to work by and with that violence.

Our bodies are dead matter breathed briefly into life. We can choose to be grateful for how we carry these unknown dead within us, for the life they give us.

Harlem

Morningside Park offers my favorite view of Harlem at night. The borough stretches out beneath us, blurry and studded with streetlights. I am tired and having difficulty seeing. I can focus on the smaller details of your face, the lavish curve of your eyelashes, how the bridge of your nose calms me. The rest of you is too vast to comprehend—but this has always been the case.

Who is the LTTE? you ask, as we descend into the park.

It’s Veteran’s Day here in the US, a public holiday. You’ve had the day off work, and the city is in repose, hushed and in shadow. At the grocery store a little later, the radio will recite chipper thanks to the military. In a few weeks, this country’s president and commander-in-chief will declare war on Iran, before being sidelined by a virus galloping across the globe. We don’t know any of that, yet. In the fruit and vegetable aisle, I will snort at all this perky and macabre patriotism.

Then I will remember how you were raised beside the country’s oldest naval site. I will think of how you and so many other people of color I’ve met here nearly joined the US Army.

War wisps through our everyday, tendrils of smoke.

But back at the entrance into Morningside Park, calmly, I explain. I reach out from the island’s independence to those early heady days of trade unionism, from the implementation of majority-rule democracy to the disenfranchisement of Tamil hill country workers, from the crushing of the Sinhalese Marxist movement in the South to the rise of the Tamil Tigers in the North.

I make good time: we have crossed the park’s breadth and are exiting at 116th street as we approach the year 2009. It becomes harder to speak now. My bird’s eye view begins to shrink in on itself, history encroaching into the here and now.

Flatly, I explain how the government, having already bombed hospitals, schools, and orphanages, set up a no-fire zone. Mercy in madness. I explain how the UN withdrew its workers. I explain how international journalists were banned from the area.

After the carnage, there are waves on the beach, blood in the water and sand.

Mullivaikkal: a site-name mouthed like a prayer grown greasy with overuse. A quarter of a million people, I say, repeating something M had said in Jaffna, trapped on a beach the size of Central Park. And then the Sri Lankan government started shelling.

After the carnage, there are waves on the beach, blood in the water and sand.

M’s analogy has taken on new resonance since moving to New York.

I was not able to visit Mullivaikkal beach on this trip. We made it as far as Mullaitivu before we were delayed. The sky had glowered and briefly there was rain. From inside our hired van, I had wondered what the beach was like in that kind of weather. The day was bright with heat when I had gone the previous year, the debris of the dead and missing pockmarking the sand with blazing light.

In your kitchen, you ask me about the trip. I am silent for a few hours, and you are unfazed. In the quiet, you tell me about wanting to move to the Bronx, about your worries for your students, about training to fight. As you talk, soft noise, I rest in the curve of your neck.

It is later, as you’re falling asleep, that I suddenly burst out: I want to tell you everything. Calm and clear, you say, So tell me. I am grateful for the patient heft of your voice. It is something to hold onto.

But I don’t know where to begin. This is a cop-out. There is no beginning; this is the always-already of mass death, at once monumental and individual.

I have defaulted in the past to talking about this war almost only with people who already were living with or through or because or despite this particular war. But our dead line our dreams, their deaths becoming more and more commonplace, said Audre Lorde in 1986, about police killings of Black people in the US.

Yes, a cop-out: I step close past the police officers and the police cars phalanxed outside Madison Square Park. I collect my employee card from armed men and women, their hips heavy with weapons, on this Harlem campus that declares that itself a sanctuary school, to teach in a program where my students write about being undocumented. At the subway, I open the emergency gate for a man in a wheelchair. You must be from New York, he says, wheeling himself into the station, everyone else was too afraid. Last week, at three different stations in two different boroughs, transit police drew arms on commuters accused of fare evasion.

War is everywhere here in this city I am reluctantly falling in love with. There are soldiers in Penn Station, camo-shaded like the deserts they have been invading. But for the flat black of their guns, they blend into the sandstone walls they are protecting here. Drawn from the state’s Army National Guard, Air National Guard, and Naval Militia, the soldiers are all volunteers. They are gathered on active duty status under the umbrella of the Joint Task Force Empire Shield, created after 9/11. As ravenous as the war it serves, the Shield’s budget has only grown with every passing year.

We believed / we believed, writes Aja Monet to Palestine from Brooklyn, in the sanctuary of peace / they should’ve told us / it was war.

If we are lucky, writes Christina Sharpe, about slavery’s afterlives, we live in the knowledge that the wake has positioned us as no-citizen. If we are lucky, the knowledge of this positioning avails us of particular ways of re/seeing, re/inhabiting, and re/imagining the world.

The truer thing is to lean into your gentle quiet, how you draw me out of myself, waiting on the shoreline of our differences.

It has been easy to pretend that people from the island would require less explanation of ourselves to each other. But I have struggled, after all, and still do, to articulate anything clear about what it means to be Muslim and speak Tamil on this island, where religion and language is limned on all sides by death and division—I have been able to articulate little that is clear to myself, let alone to anyone else from this war. I find solace in Édouard Glissant exclaiming on the topic of solidarity that as far as my identity is concerned, I will take care of it myself […] it does not disturb me to accept that there are places where my identity is obscure to me.

It has not been true that people from the island would understand it better. The truer thing is to lean into your gentle quiet, how you draw me out of myself, waiting on the shoreline of our differences. Your care is a pull like the tide.

Even in the dark, it is astonishing how the light falls on you, how it spills over the planes of your face. I am abashed. You wear your body like skin, I say, half-asleep and unaware of having thought the words before saying them. You break out in a grin, bright. Your mouth is a provocation. You’ll write that one day, and I’ll know it’s about me. Yes.

After the desolation, after the razing, there are the waves on the beach, there are the memories and the matter of the strangers we carry unknowingly in our bodies, fleshing out our blood, giving weight to our breath, soft as ash behind your earlobes, salt like the sweat at the base of your neck.

In the morning, your eyes are smudged with a new softness. Harlem at daybreak is a boon.