All names in this essay have been changed to protect the students and protestors.

I hadn’t heard from Navila in over 72 hours. Her silence was unusual. In the midst of the protests against India’s recent Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), her phone, with WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and Twitter, was the lifeline that connected her to the larger network of students, organizers, and other protestors. She always responded within seconds; most days I would wake up to multiple memes, voice messages, posters, and ground updates on my various messaging apps.

*

Passed in December 2019, the CAA is India’s equivalent of the Nuremberg Laws. It violates the secular principles of India’s constitution and introduces religion as the basis of citizenship, allowing Hindus, Parsis, Jains, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Christians persecuted in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan to acquire citizenship while excluding persecuted Muslims communities from the region. Ahmadis in Pakistan, Hazaras in Afghanistan, and Rohingyas of Myanmar are excluded, as are Tibetans, Sri Lankan Tamils, Chins from Myanmar, and other protected groups. The National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT), a Delhi-based rights group, has said that “the CAA has made about 6,00,000 lakh refugees in India forever stateless and vulnerable to refoulement.” The act, along with the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC), would require every Indian to prove their citizenship, an exercise that would deny citizenship to large numbers of Muslims and other marginalized undocumented communities.

When the CAA was first introduced, millions of Indians across the country took to the streets. I was one of them. Navila, a university student, first contacted me in December 2019 with a request to amplify the protests in Delhi on Twitter, which, in light of a media crippled by state repression, has become the default place to share information. There, citizens transformed into organizers, reporters, and frontline historians, highlighting protest locations, SOS calls, detentions, and calls for gathering.

*

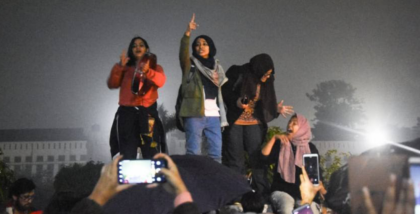

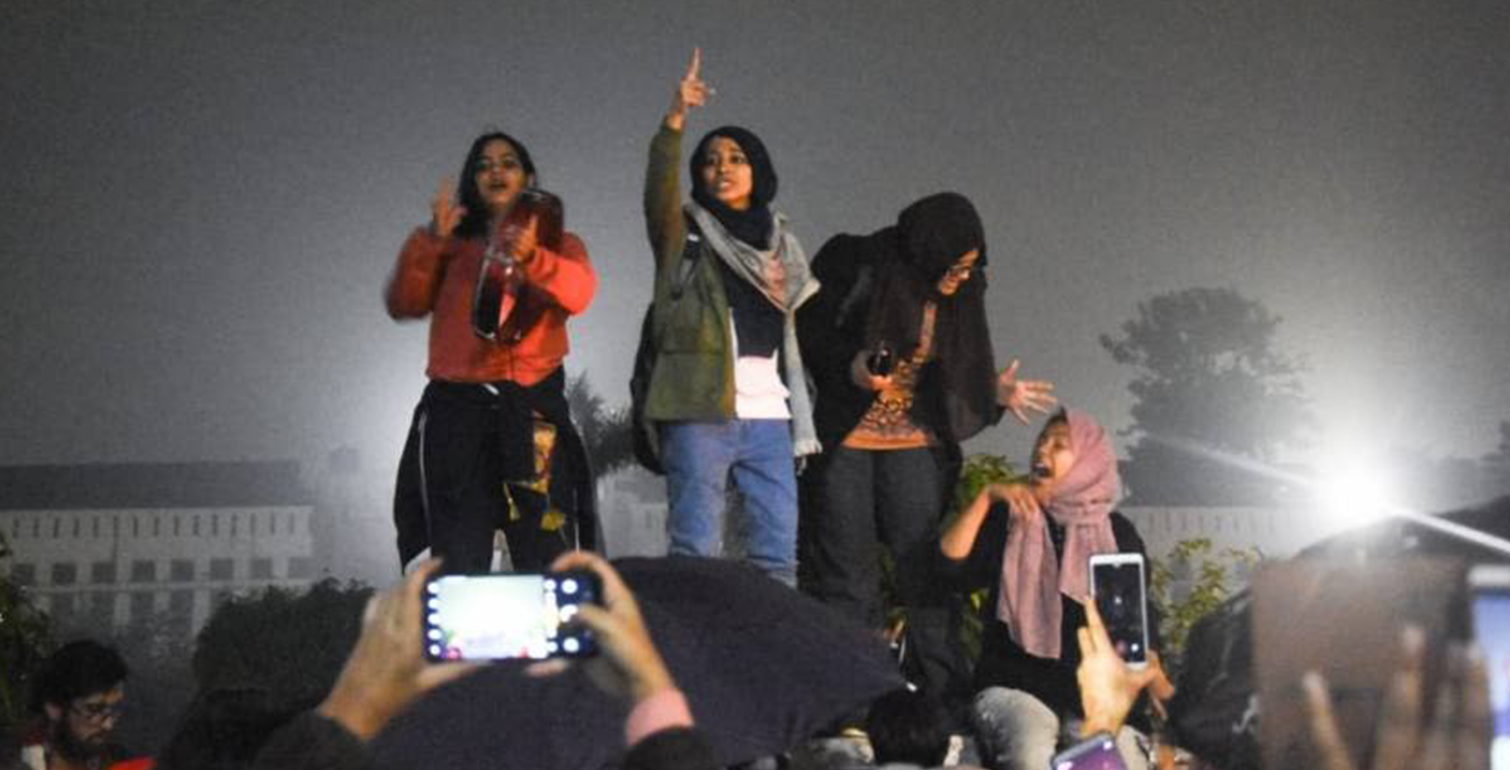

Soon after I met Navila, a text arrived with an image of three students from Jamia Millia University in Delhi—Ladeeda Sakhaloon flanked by Chanda Yadav and Aysha Renna, raising slogans against the CAA, with the accompanying text—“We are dancing on the streets for freedom.” Students at Jamia Millia and Aligarh Muslim University in Uttar Pradesh had begun nonviolent protests. Within days, the police stormed both the university campuses. Students who hid inside washrooms fearing baton charges were beaten up. Tear gas was fired inside the library and students were dragged outside, beaten, and arrested. The siege lasted for over five hours and more than 100 students were wounded.

Attacks on students brought more people on to the street. Muslim women of varying ages, most of them from poor neighborhoods occupied an area called Shaheen Bagh for over three months, braving the rain, cold, and attacks from right-wing groups. The women of Shaheen Bagh inspired over 100 other women-led permanent sit-ins through India.

Sparks of revolution were in the air. Images of B. R. Ambedkar, Gandhi, and Dalit activist Rohith Vemula appeared at protest sites. The protesters read the constitution and sang India’s national anthem. Coined in 1921 by poet and freedom fighter Maulana Hasrat, the slogan Inquilab Zindabad—Long Live the Revolution—once the rallying cry for Indian independence against the British, was reclaimed and raised against the Modi government.

Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poem “Hum Dekhenge”—We Will See—written in 1979 during General Zia-ul-Haq’s authoritarian reign in Pakistan, was also circulated, as was poetry by members of Assam’s Miya community who had been charged with sedition.

The police regularly worked with armed thugs and political mobs to suppress resistance and dissent.

Write me down

I am an Indian

Write it down

My name is Ajmal

I am a Muslim

and Indian citizen

As the protests progressed, so did police brutality and hate speech. In Uttar Pradesh, 36 Muslim boys were illegally detained and tortured. Navila, along with her cohort of student-organizers, asked if I could help track the growing police violence against citizens.

At the Polis Project, a hybrid research and journalism organization that I founded, we set up an anonymous system to track, log, and document instances of state violence against the protestors, from illegal detentions and use of tear gas to custodial torture and surveillance. Mapping the ecosystem of violence, its abettors and enablers, helped us understand how the dissent was being crushed through administrative and policing techniques. Violations of fundamental rights became ubiquitous. The police regularly worked with armed thugs and political mobs to suppress resistance and dissent. Their use of arbitrary and extrajudicial violence went unchecked without any remedial action.

*

As the violence ebbed and flowed, and the protests spread across the country, Navila and I were constantly in touch. Some days Navila would call and narrate what she had witnessed on the front lines, and I would quickly log these testimonies as audio ethnographies. The calls started arriving later and later into the night, each longer than the one before, and darker. Ours was an odd friendship forged in the middle of chaos, fear, and arrests.

I then began recording conversations with other students, some in person, some over the phone, sometimes in groups and other times in email threads and messages. As the protests burgeoned, so did this repository of conversations, marginalia, images, and group messages. In these conversations, the students spoke about themselves, their family histories, and why they were protesting. They spoke with hope and fear in equal measure, but the question of violence loomed in all the conversations.

What would they do when the mobs arrived at their doors?

How would they protect themselves?

Did they have the right to self-defense? If they protected themselves, was it still violence?

Navila and her friends grew up in shadows of 9/11, the rise and normalization of global Islamophobia, and the series of anti-Muslims riots and pogroms over the last few decades in India. Born in an unequal society, cast as unwanted citizens, and baptized by violence, defiance against Modi’s authoritarian India was their last stand.

While violence against minorities in India has always been chronic, by the 1970s, winning elections by appealing to majoritarian sentiment against Muslim and other marginalized communities had become a well-honed strategy. This culminated in three events that fundamentally transformed India—the pogrom against the Sikhs in Delhi in 1984, the destruction of the Babri Masjid at Ayodhya by a mob of thugs from Vishva Hindu Parishad, a militant right-wing Hindu nationalist organization, and the slaughter of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002.

Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014, Muslims have become disproportionate victims of violence, especially lynchings. There were 47 cow-related hate crimes between May 2014 and April 2019, and 76 percent of the victims were Muslims. Hate speech by Modi and his ministers has been widespread and ongoing; for instance, Amit Shah, India’s Home Minister, has called Muslims “migrant termites.” Numerous students, lawyers, professors, rights activists, protestors, and others challenging the government have been charged with sedition.

In the wake of Modi’s reelection in 2019, the government has aggressively implemented policies that seek to remake India into a Hindu nation. In the first 100 days, the Modi government unconstitutionally revoked the special status of Muslim majority Jammu and Kashmir, putting over 8 million Kashmiris under an unprecedented information blockade; the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act was amended to designate individuals as terrorists unilaterally; and the Right to Information Act was diluted. This was followed by India’s Supreme Court ruling in favor of Hindus over the Babri Masjid dispute.

It was no longer just the fear of living with discrimination or surviving iterations of violence—they saw a road map to complete annihilation.

On August 31, 2019, the National Register of Citizens (NRC) released a list of names in the state of Assam, which effectively rendered 1.9 million people stateless, many of them Muslims. In response to this, Genocide Watch issued two alerts — first for Indian-occupied Kashmir and, later, Assam, stating that, “Preparation for genocide is definitely underway in India… The next stage is extermination.”

In November 2019, the government announced that the National Register of Citizens (NRC) would be implemented nationwide to identify “undocumented immigrants” and would require Indians to provide evidence of their citizenship. Those declared as “foreigners” through this process will be held in the various detention centers currently being built across India.

Then came the CAA, the coup de grâce: a clear articulation of the government’s efforts to systematically transform India into an ethnonationalist state, where millions would be stateless subjects stripped of rights.

*

Navila and her friends saw the anti-CAA protests as the final battle to protect what was left of their inheritance as citizens of India and the secular constitution that B. R. Ambedkar bequeathed to them. It was no longer just the fear of living with discrimination or surviving iterations of violence—they saw a road map to complete annihilation.

Born and raised in Hyderabad’s old city, Hanif was the oldest among the student protestors, and deeply familiar with such cycles of violence. In 2007, his uncle was picked up by the police and unlawfully detained and tortured soon after the Mecca Masjid blasts, explosions inside the 400-year-old mosque in Hyderabad’s old city that killed 11 people. Hanif was only ten, but remembers those days with clarity. For four months, no one knew if his uncle, then 19, was alive or dead. The police never informed the family of his uncle’s whereabouts, and his grandfather was beaten when he approached the police station to lodge a missing person complaint. Last year, Hanif interviewed his uncle when he turned 30, and learned that he had been stripped naked and tortured. “They used slurs, called him a terrorist; they beat him mercilessly,” he told me. When his uncle was finally released, the state offered compensation of 30,000 rupees ($400) for the “error” of “torturing him by mistake.” The only difference, he says, between violence against Muslims then and now is that “there was no cell phone with a camera before.”

Tabish’s parents both survived the Bombay riots of December 1992 and January 1993, which erupted after a protest by Muslims following the destruction of Babri Masjid was met with violence. His grandmother witnessed bodies floating in the canals soon after the Meerut riots of 1987, and his grandfather was a little boy during Partition. Tabish’s earliest memories are stories of Partition and prayers being performed in the name of those who had died. In our conversations, Tabish spoke about the fear most young Muslims live with. “We are so used to this fear, we think it is normal… I saw people circulating videos of Junaid, a 16-year-old boy being lynched on the train.” Junaid was traveling back to his village in Haryana after shopping in Delhi for Eid in June 2017. Tabish was in his ancestral village in Meerut when the news broke, and a week after, when he boarded the train from Meerut to Delhi, he told me that fear had taken over him completely. “I shaved my week-long stubble… and kept to myself the entire journey.” Even in the city, traveling on trains made him uncomfortable. A month after the Delhi pogrom, he told me, “I have witnessed my first pogrom; inshallah, this will be my last.”

Zainab is training to be an accountant, but since the protests started she has been painting murals and dropping off water bottles at local sites. When I briefly met her in Delhi, she was painting a poster that said “Muslim Lives Matter.” “This is my land, no one can make me a foreigner here,” she told me. Her mother and sister were taking turns sitting in one of the smaller encampments in their neighborhood. With winter rains and no protective cover, everyone feared that the women might get sick. “They are building detention camps, and if we don’t fight now, we will end up there, but my mother says it’s better to die protesting in the rain than dying as a foreigner in the camps.”

Towards the end of our conversation, Zainab said: “I lost my grandfather and my aunt.” For a moment I didn’t quite understand what she meant, until she finished her sentence after a long pause. “We haven’t returned home to Gujarat. We left everything behind.” Zainab has no recollection of her home in Gujarat; it was burned down during the 2002 violence, which displaced some 200,000 people, mostly Muslims, from their homes.

The pogroms in Meerut, Bombay, and Gujarat are not unknown, but the men who orchestrated them have not only escaped accountability for their crimes but now rule India with an electoral majority.

*

Beginning on February 23, 2020, North East Delhi’s Muslim communities endured a series of violent incidents by mostly Hindu mobs, including the destruction of property, attacks on mosques, and desecration of graveyards. Armed mobs first marked, and then firebombed, Muslim homes and businesses. They chanted the rallying cry “Jai Shri Ram” as they set fire to a local mosque and planted Hindu-nationalist flags on its minaret.

The perpetrators dumped bodies and severed limbs into open drains. Messages arrived in the WhatsApp group run by activists with a grotesque photograph of a bloated body and alerted us that more bodies had been fished out of the drain in the aftermath of the pogrom. The unofficial death toll was 60, and the confirmed number fluctuated as various newspapers misspelled names, counted the dead twice and sometimes erred in confirming the reports. After I saw the photographs, I called Navila’s number; the messenger rang for forty seconds and then stopped.

*

On March 8, 2020, I emailed all the student protestors, including Navila, the edited transcripts of our conversations, asking them to look over the texts as I began to write this piece. These conversations were biographies with detailed family histories; their relationship to the state; their grievances, struggles, and hopes; their political beliefs; and nuanced and articulate critiques of Indian nationalism and its deep failures. They also laid out how the various local groups, and communities were mobilizing.

After a week, I still hadn’t heard from anyone.

After days went by without any communication, a familiar feeling of fear and discomfort took over. I checked my messages repeatedly, and looked at Navila’s Twitter handle; the last tweet was over 48 hours ago.

Who should I call to check in on her?

Would a call raising concerns about her silence create more anxiety?

Was she missing or was she hurt?

How long do I wait before I write to her again, how long before I start alerting people?

These were questions about life and death, logistics and resources. Everyone I knew in Delhi—lawyers, activists, organizers, journalists, students, and the various community leaders organizing local protests—was exhausted and overstretched. A call requesting one of them to check on Navila meant burdening those already overburdened.

I waited.

*

On March 14, at 3:30am, I missed a call from Navila. In the morning, I woke up to a voice message: “They picked up Hanif and just released him, he is ok, I will email you.” Around 8:30am, an email arrived.

“We think the Delhi police now has informants… Things are really bad and have gotten worse since the 23rd violence. As a group, we have decided not to go ahead with the interview at this moment. We are really sorry, but no one is safe.”

Hanif, like his uncle before him, had been detained and released after a few days. I don’t know the details of his detention, where and why he was picked up, or on what grounds. His phone remains switched off; the messages I have sent to him remain unopened. Beyond that email, Navila hasn’t told me what transpired in the aftermath of the pogrom.

We agreed on small fragments from our conversation that I could reveal in this essay, but beyond that, everyone has gone quiet. Just a few weeks before they had felt invincible, but now the world had changed.

Chronicles of carnage emerged soon after the pogrom in Delhi, but the real extent of violence remains unclear. In addition to the estimated 53 people who died, many others, including children, are missing. 85-year-old Akbari had survived Partition and other riots, but died inside her home when it was set on fire. Musharraf, of Gokalpuri, was lynched before his daughter as she pleaded with the mob for mercy. The bodies of 16-year-old Mohammad Hashimand and his elder brother Mohammad Amir were dredged out of a drain.

On the third day of violence, 7,500 emergency calls were made to the police control room throughout the day, yet no one arrived to protect these communities. Instead, the first-person accounts and videos I logged suggested that the police worked with the rioters, aided and abetted them, and in some cases even attacked the victims. In the aftermath of the violence, many residents have fled their homes, and remain homeless.

Silence lays bare the ground realities in India. They found refuge in words left unspoken, unpublished.

As I read and reread Navila’s email, and processed their collective choice to withdraw their voices, stories, ideas, and angst from the public realm, it became clear that this was not voicelessness, but an act of self-defense. While they decided not to speak, their choice of silence lays bare the ground realities in India. They found refuge in words left unspoken, unpublished. In the face of such overwhelming state brutality, it might be the only possible space for healing. Silences surrounding violence in India are neither new or unique. These silences teach us about the precarity of dissent, but more importantly, how violence has already reshaped India.