Osheen Siva

Osheen Siva

What does a land think when its people are imprisoned in their homes; when all is made to fall silent? When soldiers descend onto the streets like cockroaches raised on a diet of nuclear bombs, and beat hungry dogs that warn of invaders?

Does the land pray, or does it curse?

What does it whisper to its waterfalls, to its verdant forests, to its barren stretches? Does it wait for the pain of the jackboots to subside, or does it harness the silence sitting still on the broken asphalt for immediate deliverance?

In the last six months, I have imagined my homeland in Kashmir, the part occupied by India, bereft and alone in a black hole. I have imagined the land and its people between frenzy and patience; between hope and desperation; between abandon and restraint; between protest and silence. But more so in silence—the kind that India has enforced on the wounded, battered body of the land and its people.

*

In August 2019, I wake up in Colorado, where I teach, to a profusion of news not from Kashmiris, but about Kashmir. Across TV channels and the internet is the Indian Minister of Home Affairs, Amit Shah, on repeat, announcing that Kashmir’s integration is “complete.”

The word integration sounds benign, but its violence marks each Kashmiri body. When I hear the word uttered, this festering wound breaks open, begins to bleed again.

In the weeks prior, rumors had been flying like confused bats. The Indian government had flown in 48,000 more troops in addition to the 700,000 already occupying Kashmir. The valley was emptied of all non-Kashmiris, including Hindu pilgrims, students, and daily wage laborers. No Kashmiri local knew what was happening, nor did the government confirm. As the region was being tightly sealed off, people stockpiled food and gas and waited for information.

But on August 5, 2019, the chaos became clear: Article 370, the section of the Indian constitution that established Kashmir’s quasi-autonomy and indigenous rights, was being eliminated. Kashmir would be annexed as a part of India, under the pretense of consolidating the nation’s so-called rightful boundaries.

In 1947, when India and Pakistan gained their freedom from British rule, Kashmir lost its own; instead, it was caught in the middle and divided up. This set in motion years of regional conflict as well as a popular armed resistance movement, which the Indian government has met with a brutal occupation, massacres, disappearances, rapes, arson, mass blinding, and rampant arrests.

In August 2019, the spectacle of power wielded by the Indian state was supercharged with ethnonationalistic zeal. The government detained and arrested local client politicians who had run sham governments for India since 1947. Imprisonments swept up average civilians, resistance leaders, human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, even children. At one point, an estimated 13,000 children were in detention on suspicion of being protesters.

Now, the threat of settler colonialism, which has loomed over Kashmir since 1947, was becoming a real possibility.

While Kashmir’s special status under Article 370 had long been largely symbolic—the region has been subjugated by India for decades—its removal marked a significant turning point. The last vestiges of Kashmir’s sovereignty were gone. Now, the threat of settler colonialism, which has loomed over Kashmir since 1947, was becoming a real possibility.

*

On August 4, 2019, my parents visited the shrine of the medieval Muslim saint Hazrat Amir Kabir, popularly called Khankah—an enduring symbol of the spiritual, political, and cultural independence of Kashmir. They sent me a photograph of the shrine in the hopes of including me in the blessings. They had pledged to visit the shrine for seven days of supplications, but only managed to go once. The next day, I lost all contact with my parents. They along with roughly eight million Kashmiris disappeared under a curfew and communication lockdown, imprisoned inside their homes as the Indian government imposed a siege on the region.

On August 13, 2019, the 9th day of the siege, I wrote in my journal:

eid passed peacefully through checkpoints, razor wires, and children that know how to stay still

*

Indians rejoiced, as only invaders can. Streets and social media were abuzz with discussions about prying Kashmir open for Indian plunder. Kashmiri men were demonized as “terrorists” and “fundamentalists.” Meanwhile, the fetishization of the land of Kashmir and Kashmiri women became a mark of righteous patriotism. Indian politicians and civilians alike called for kidnapping “beautiful, fair” Kashmiri girls. Others announced their settler-colonial dreams of acquiring Kashmir’s fertile lands. India has masqueraded successfully as the largest secular democracy in the world, but with the annulment of Article 370, its imperial heart was on full display.

A handful of Indian voices did dissent, but their disagreement was completely misplaced. They disagreed with the method of the removal but did not see the annulment as illegal or a constitutional wrong. At most, these voices decried that the Kashmiri legislature, which had been dissolved anyway in 2018, was not consulted, nor were local client politicians (who, in any case, had already long been carrying water for India). Forcible “integration” of Kashmir unified Indians of all shades.

The cacophony of opinions crescendoed in the Indian media while Kashmiris themselves were severely silenced. In addition to a strict curfew, the internet, cellphones, and landlines were suspended, curtailing all contact with the outside world but for a few basic TV channels and radio.

Like many Kashmiris in the global diaspora, I desperately wanted to know what was happening back home. Digging through my old phone books and discarded cell phones, I looked for the numbers of forgotten and dead relatives, hoping that maybe one of them would work. Defeated, as days passed, I realized it was a futile exercise and that there was no possible means of communication. This lasted until late September 2019, when the small number of landlines in Kashmir were slowly opened. While some cellphone capabilities were restored towards the end of 2019, Internet services continue to remain affected. In January 2020, the 2g internet connection was allowed with only 300 whitelisted sites, and no social media.

August 19, 2019, the 15th day of the Kashmir siege:

add to the handicrafts of kashmir: how to extract metal pellets from kashmiri flesh. “if you live here, you have to know how to do it,” they say, wincing, paisleys soaked red

*

The Indian media and government used the word “normalcy” in the sentence that announced the curfew and communication lockdown in Kashmir. For those powers, silenced, imprisoned Kashmiris amounted to everything being normal in the valley. What they seemed to suggest was that Kashmiris, as is their norm, were not protesting in the streets or throwing stones at Indian soldiers. This was not necessarily true.

Mass arrests without warrants affected Kashmiris’ ability to protest en masse, but reports revealed that protests were still taking place, just not being covered in the Indian press.

All Kashmiris know curfew intimately. It is like a recurrent boil, painful and traumatic, a silent blot of the body of our homeland.

The massive deployment of soldiers ensured that the curfew was extremely strict. A young Kashmiri woman gave birth by the roadside after having to walk six kilometers in an attempt to get to a hospital. Troops were strewn across neighborhoods and standing by doors that opened onto streets literally caging people inside. More than usual, the region was woven with razor wires. Each area was so wound up that even close neighbors could not cross over to meet each other. Thus, the simplest of allies—lifelines for sharing food, medicine, or words of support—became inaccessible. As a friend of mine put it, this choking tactic was enforced to “bring Kashmiris to their knees and acquiesce with Indian policies.” Kashmir, famous for its green meadows, saffron plateaus, and teeming waterfalls, was living up to its title as the world’s most beautiful prison.

August 20, 2019, the 16th day of the Kashmir siege:

mother, jails are overflowing with lovers old and young, wounded and maimed, blinded and blindsided. you may have to offer your home as a prison.

*

All Kashmiris know curfew intimately. It is like a recurrent boil, painful and traumatic, a silent blot of the body of our homeland. Every Kashmiri is a political prisoner. When you are under house arrest, the end of your yard, if you have one, is the limit of your movement. If your home opens directly into the street, you cannot even open the window, let alone the door. Curfew means you lurk around the house, you eat what’s left, watch TV if fortunate enough to have some electricity, and read and reread everything lying around. Phones and the internet are habitually cut off.

In my childhood, during curfew the milkman would become a messenger passing notes among me and my friends. We would commiserate and plan to meet when the curfew lifted. Sometimes it would be a day or two, sometimes a week, and sometimes a month. Its intensity increased from 2008 onwards, as did civilian resistance, with street fights and stone wars becoming central to the Kashmiri Tehreek resistance movement. Everything—music, art, poetry, fiction, film—became a paean to resistance against India. It was the Kashmiri Intifada. The people’s clamor for azaadi, freedom, refused to dissipate and was also bolstered by burgeoning online and offline solidarities. Meanwhile, the Indian government’s repressive policies grew more brutal, with killings and pellet shotgun-induced blindings increasing and freedom of expression a perpetual casualty.

In the initial days after the removal of 370, the international media reported on Kashmir with unprecedented vigor. Were the media sympathetic because of human rights violations, or were they coming to understand the just struggle of Kashmiris? Was it fear and guilt over the rising specter of fascist Hindu supremacy that had also made headway in the West? But it didn’t last, as India banned most of the foreign press from entering Kashmir. Only a handful, like the BBC World Service, remained active, but not without controversy. In one instance, the BBC captured footage of a massive protest in the valley, which the Indian media swiftly denounced as fake.

August 28, 2019, the 25th day of the Kashmir siege:

the soldier shouted: “we didn’t beat you, did we?” deep purple welts across their back and legs, eyes swollen with little lead pellets, the kashmiris nod vigorously. in one voice say: no sir, you didn’t.”

*

The pain of occupation and its contraptions weigh on every inch of Kashmir’s body. Yet despite the bunkers, barbed wires, checkpoints, lookouts, and military surveillance, the force of life is always palpable. In Lal Chowk, the red square, in Srinagar’s city center, hulking old buildings and new concrete behemoths lord over a mix of smoke-ridden minibuses, old men with skull caps and hookahs, suave businesspeople, irreverent kids, and smart hawkers and panhandlers who stream in from India during summer months. The Jhelum River cuts a neat line through the city, and beside it, a promenade called the Bund is a beloved place to stroll. Everyone from tourists to the valley’s denizens to cultural icons like the late poet Agha Shahid Ali covet their walks on the Bund. It also has a good share of harmless junkies and endearing local crazies.

What was the Bund thinking during the siege? Was it waiting for people or was it taken by its own quietness and the melancholy of the Jhelum flowing by? I recalled one man who often stood out there. He looked like an avant-garde fashion icon; tousled hair and ragged clothes that from a distance appeared to be a high-end outfit made from distressed fabrics. In reality, he was suffering. With a piece of charcoal in his hand, he would stand in front of the walls surrounding the civilian and military government buildings like a painter waiting for inspiration. He would often draw English letters, incoherently strung together.

He would also draw hybrid animals: cows with snouts, box-like torsos, circles with tails, and scenes of defecation. It was easy to disregard his graffiti as nothing but the ministrations of an unstable mind. Kashmir has seen a growing number of people suffer from mental health issues in the past three decades. The fallout of a brutal protracted war and daily harassment and torture at the hands of Indian troops is that most Kashmiris live with undiagnosed PTSD.

I never knew the graffiti artist’s story, but in one particular instance, what he had drawn caught my eye. Within his long ramblings was the word ARMY. It more or less summed up the imaginings in which he and his land were caught.

What was he doing these days? Where was he? Was he even alive? These questions were constant companions as the siege and its silence stretched on.

September 15, 2019, the 42nd day of the Kashmir siege:

we entered another long dreadful night. winds bring terrible knowledge. following the cries of boys, and mothers wailing, is an angry river of silence threatening to drown beating hearts.

*

Summer changed to fall and then to winter. We wrote 2020 but most Kashmiris were frozen in August 2019. Nothing was changing in Kashmir. Under lockdown, one news report mentioned that Kashmir, already facing scant electricity, was out of candles.

After 120 days of the siege, the Kashmiri diaspora began to notice that WhatsApp contacts inside Kashmir were leaving chat groups. It was eerie. I saw my father leave, my sister leave, my cousins leave, my friends leave. Public chats were emptying of Kashmiris. It turned out that WhatsApp was throwing them out for inactivity. Kashmiris had disappeared from the internet, social media, and from the news cycle, collectively forced into an information black hole.

Once, during the siege, my sister called me. The local administration had set up telephone booths for people who needed to contact their loved ones outside the valley. Even though she had not been able to reach our parents and did not know the fate of most of our immediate family, she said they were mazzes manz—enjoying.

Tche rozzi khosh, she said, meaning you stay happy.

She assumed an unusual singsong voice. We talked all of one minute and 56 seconds before the phone was abruptly cut, most likely handed to the next person in line. Radio silence from home followed me for many weeks after. The pain of a sudden and inadequate call was exacerbated by the humiliation Kashmiris experienced as they waited in long lines to make a connection. It reeked of concentration camps, where prisoners had no choice but to seize upon fleeting, unsatisfactory chances to reach the outside world.

October 17, 2019, the 74th day of the Kashmir siege:

Kashmir is a waiting. an endless in-betweenness. a tear, a touch, a sniff; a word waiting to drip from lips. when they lift the siege.

*

I would often think of my parents, especially my mother, my rock. Growing up, mothers are often hard like a washerman’s stone, against which one prepares for the vagaries of life. In time, weathered, mothers become softer than soapstone, and as fragile. My mother was the same; after I left Kashmir, she needed me to call her every day. My father said she would not sleep until I called. During the siege, this knowledge became painful; there was little I could do for her.

But I also knew that my mother, imprisoned in her home, would be doing what all Kashmiris do. They lift themselves up with prayer, and its power resonates. More than five centuries of tyranny from different rulers have taught Kashmiris how to access to inner reserves of strength. Prayer has evolved as part of the culture of resistance.

Everyday resistance in Kashmir is like a river. It runs steadily and quietly, gathering force, coursing on, as it always has.

Some colonial historians have observed that Kashmiris were called zulmparast—worshippers of tyranny—because of their capacity to bear pain and torture. Through different occupations, from the Mughals to the Dogras and now India, the indigenous Kashmiris have always been shorn of power, heavily taxed, and brutalized. Under Dogra rule, the extent of tyranny was such that even basic knives were confiscated from the Muslim community and a license was required to sacrifice a chicken. The succession of tyrannical regimes sought to render the people completely powerless.

Hence, prayer becomes a weapon. Men storm the streets to offer prayers as a mark of protest. Women flock to shrines across the valley to register their protest before Allah, the only adalat (court) they still trust. In 1931, on July 13, when under the despotic Dogra rule Kashmiris were demanding an independent sovereign democracy, 22 men who were a part of the prayer protest were killed by royal soldiers. For Kashmiris, prayers and protest coalesce and inform each other. Fridays, the day of mandatory afternoon congregation in the Islamic calendar, is a de-facto day of protest in Kashmir.

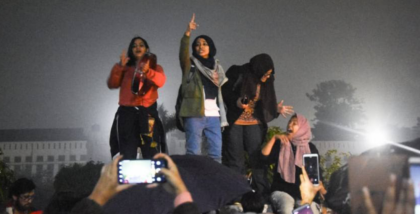

For the last six months, prayers have been banned at the major sites of worship. But Kashmir’s restive heart still stirs. In the outskirts of the Srinagar city, in the town of Sowurr, a small neighborhood called Aanchar (meaning pickle in Kashmiri) has become a hub of protest despite the crackdowns and curfews. The people of this working-class town dug up the roads and set up barricades. They impeded the army trucks and police jeeps from entering and making arrests. Everyone from the community, including women, stood guard during the nights. When Indian government forces attacked them with pellet shotguns, they did not take the wounded to the nearby hospital for fear of being arrested. Instead, a few nurses and self-trained volunteers tended to the hurt. While the entirety of Kashmir was curfewed during Eid and not allowed to pray, the residents of Aanchar not only met for prayers, but also held a protest.

*

It is April 2020, and Kashmir is under its longest-ever communication lockdown. The region is emerging from the grip of an icy Himalayan winter. The economy has been hit hard. Local media is censored and in a frightful slump. Many journalists have been rendered jobless. A photojournalist with a baby on the way became emblematic of rising desperation when he was forced to abandon his profession and pursue odd jobs. Many professionals and students are leaving to escape the punishing tactics of the Indian counterinsurgency and the scourge of growing unemployment. The internet ban is still largely in place, with the government allowing only 2G, which is text based and excruciatingly slow.

In March, when the Covid19 pandemic erupted, the internet continued to be curtailed, despite Kashmiris’ clamoring for timely information. After the Indian government declared a 21 day lockdown, despite the dangerous health emergency, it announced an amendment to Kashmir’s historic domicile law. This allows for non-Kashmiri government officials (who have served for a certain duration) to be treated as domiciles, which will mean rights to franchise and property, as well as employment. The long-feared policy of Indian settler colonialism in Kashmir began unfolding right before the quarantined eyes of Kashmiri people. Even with the partial communication lockdown and quarantine in place, the Indian police chief in Kashmir openly threatened Kashmiris against critiquing these unilateral changes, warning that law enforcement were monitoring online content and criminalizing any forms of protest.

But the enforced silence does not mean rest or calm, nor does it mean Indian policies are readily accepted. India changing the status of Kashmir internally does not change the status of the region internationally. India’s unilateral actions are illicit, and will not pass legal muster if the United Nations decides to bring to fruition the Kashmiri demand for the right to self-determination.

On the other side of this enforced silence, I hear that in Kashmir people have taken to letter-writing again, and wristwatches are back. People use VPNs to get around the slow and limited internet. Mass public funerals for Kashmiri militants, often ill-trained young people felled by the wrath of government forces, are still taking place despite restrictions. Commemorations of various massacres committed by the Indian army, and death anniversaries of executed resistance leaders are still observed. The resistance is not subordinate to leadership; it emanates from the people.

Wild animals are a common threat to Kashmiris in the countryside. Recently, a video surfaced on the social media of young Kashmiri boys who had caught a prowling leopard. As they carried the leopard away, the crowd was jubilant, chanting a classic slogan of the Kashmiri Tehreek: “Go India, Go back!” They heralded popular militants and challenged the Naqkli Sher—fake leopards—to watch out for Kashmiri Sher—Kashmiri leopards.

It was a message from people who are brutalized but unbroken. Everyday resistance in Kashmir is like a river, even wider than the Jhelum. It runs steadily and quietly, gathering force, coursing on, as it always has. And that is what India fears.

November 5, 2019, the 93rd day of the Kashmir siege:

india, jubilant it took all the keys.

to locks that have long been discarded in Kashmir.