Illustration: Osheen Siva

Illustration: Osheen Siva

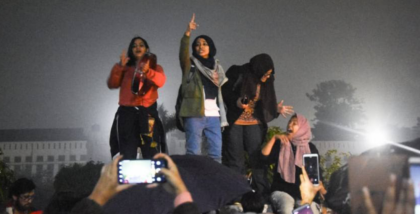

1.

Had a sudden longing to see the scenes of Saklatvala’s speeches in Hyde Park, where my own father dragged a step-ladder to speak.

It’s not clear to me what the day will bring.

I grew up here, or nearby, with this same dirt and these identical brambles and that red fox or these pears and that dandelion.

Everyone was awake when I arrived.

To have been born here and lived here, and to have gone back and forth, and then to have been gone, and now not to be gone.

Like an obedient child, but also mercury.

Dreamed of my first love.

Yes.

Today was about everything rotting and exploding.

I forgot the ivy turns red.

2.

It’s the first day.

I can’t do much more than build the world’s tiniest graveyard, for English.

What do you remember about the earth?

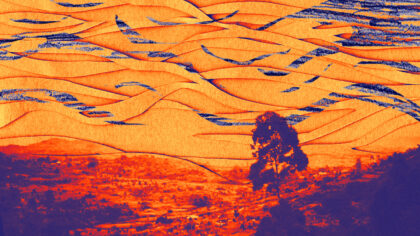

It’s early in the morning and I am drinking coffee in England, though I dreamed of my dog in the forests of Colorado. I was sitting on a grassy ledge above the forest proper. Porky surged off with a great leap and bounded through a clearing. As I followed him, I noticed a place on the ground that was charred, as if someone had made a fire when they were camping. The thick pieces of charcoal were poking up. That’s all. I lived for a long time in a forest, and then the village or town below the forest, and now I am here, with the mud and dirt of this place.

I left the flat and soon I was in the forest.

It’s strange to be living again in the country where I was born and where I lived and that I am a citizen of.

What exhausted you?

The grave and the night and the poem: a ruined alphabet.

Because I’m curious, actually, about how you begin when you have nothing to begin with.

Vertical threads.

A tiger in a cage in the garden.

I screamed!

And now it’s pissing down with rain.

Should we open a bakery?

3.

I wrote all day, describing a taxi ride across Delhi in 2014, on a day that was the most polluted day in the most polluted city on earth.

My great-grandfather spat in the face of the village chief who came to visit him on his deathbed. It was this village chief, during Partition, who had told the forty Muslim weavers in Bhulan to board trucks that would take them to safety. Just outside the village, behind the orchard that belonged to our family, the truck pulled over. The weavers and their families were asked to get out. And were shot. Their bodies thrown in the dry riverbed, a tributary of the River Sutlej that flooded each monsoon. It rained that night. “The water flowed red,” said my mother. My great-grandfather, who had developed deep relationships with this community of weavers, was devastated and enraged. He had a stroke, recovered slightly, but died soon after, though with enough presence of mind, as one of his last acts, to spit in the face of the man who had sent the weavers to their slaughter.

4.

You came so close to me, I can’t forget.

5.

This is the part of England, roughly, where W.G. Sebald wrote his novels.

Returning to the country of one’s birth after half a lifetime in a country without egrets, raspberries, or anemones is no joke.

I prefer being here (a place that doesn’t pretend to be something it’s not) versus being in a place that markets itself as progressive or radical but which replicates everything that’s so grotesque about the dominant culture itself, which is to say, its economic, racial, gendered, and ableist hierarchies.

That, of course, is not true.

I remember returning from India when I was nine, after many months away. Rocked up to Grange Park Junior School in my khaki blouse, skirt, and what I called a safari hat. Still recall the boom of Mr. Alexander—the headmaster’s—voice: “Bhanu Kapil, take that hat off at once. This is not how we do things in England. You’re not in the jungle now.” It was lunch-time. The chaos of the cafeteria stilled.

The floor shone with social copper.

6.

“How stupid do you have to be to want your entire nation to fall ill with a deadly virus?” Farhana Yamin.

Yes, that was how it was.

In the time of COVID-19.

“Survival is not theoretical.” Audre Lorde.

Yes.

Who helps [you]?

What must [we] give up?

Note: To write the first two poems, I selected a line or a phrase from every post I wrote on my blog between September 20th and November 8th, 2019, a period that coincided with my arrival in the United Kingdom after almost half my life (21 years) in the United States. The last four poems consist of lines written in the last month, also taken from my blog, The Vortex of Formidable Sparkles.