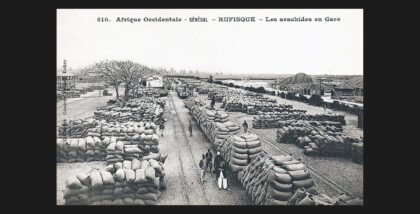

François-Edmond Fortier, Rufisque. Les arachides en gare. Archives du Sénégal.

François-Edmond Fortier, Rufisque. Les arachides en gare. Archives du Sénégal.

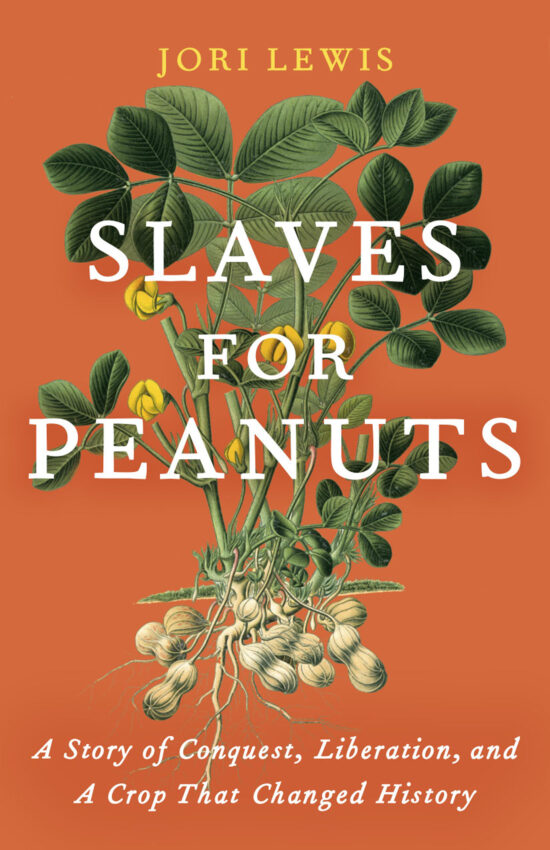

Humble and diminutive, the stature of the peanut might bely its significance. But in Jori Lewis’s new book, Slaves For Peanuts, the peanut is a grand vessel of history, one that traverses continents and empires and intersects with our greatest ideological questions.

Tracing the evolution of the peanut from kitchen-garden staple to coveted global resource, Lewis reveals how, over the course of the 19th century, the crop helped propel not just global trade and colonial expansion but also slavery in West Africa. Among her goals is to shed light on this less-told story. “People are happy to talk about the transatlantic slave trade, but there’s often silence over the question of slavery that is native to Africa,” says Lewis, who herself descends from enslaved people in America and has relatives who farmed peanuts in Arkansas.

Indeed, an instinct toward historical contradictions permeates this book. With the help of archival sources, Lewis paints a complex and character-driven picture of a tumultuous era, in which France’s imperial drive collided with abolitionist movements and “that inconvenient motto: “liberté, égalité, fraternité.” From an anticolonial Senegalese king who relies on enslaved labor to an evangelical missionary harboring the newly liberated, the book features multidimensional individuals who complicate the binaries—of exploiter and exploited, of bondage and freedom—that tend to define the writing of history.

An environmental journalist and senior editor of this magazine, Lewis moved from the US to Senegal in 2011 and has since reported on agriculture and the legacy of colonialism from her perch in Dakar. This autumn, I spoke with her about the potency of the peanut, the paradoxes of abolition, and depicting African history in all its drama.

*

Meara Sharma: How did this project—which begins as a social history of peanuts in Senegal, but expands into an examination French colonialism and African slavery—take shape? First of all, why peanuts?

Jori Lewis: When I first came to Senegal, my main objective was to explore the agricultural economy and investigate its environmental effects. So when people ask, “Why not coffee?” or “Why not chocolate?,” the simple answer is that I’ve been living in Senegal and I’m focused on this region. And the peanut was the most important crop in Senegal and the Gambia.

The peanut was so important to the Senegalese economy until, say, the 1980s and structural adjustment [economic reforms instituted widely across Africa as prerequisites for securing loans from the International Monetary Fund/World Bank], that there are whole parts of society that are organized around the farming of peanuts.

And their cultivation is concentrated in an area called the Peanut Basin. I’d been spending a lot of time in the Peanut Basin, where I was also dating an agronomist. One day he was telling me about a conflict in the village he was working in, about who should be the president of this farmers’ collective. He was like, “Oh, this guy who I thought was really smart and capable—no one wanted him to be the president of this association because he was a descendant of slaves.”

That raised a question in my mind about how of the legacy of slavery was lived in Senegal, and how people grappled with it.

Meara Sharma: You note that this is quite a taboo subject in Senegal.

Jori Lewis: People are happy to talk about the transatlantic slave trade, but there’s silence over the question of African slavery or of a slavery that is native to Senegal, and to Africa in general.

In fact, when I talk to people in Senegal about the book, they’re like, “Oh, you mean the transatlantic slave trade?” I’m like, “No. I don’t mean that.” They’re like, “Oh, you mean peanuts grown in America by slaves coming from Senegal,” and I’m like, “No. Slaves growing peanuts here.” So there’s always a bit of pushback about it. It’s a sensitive topic.

Meara Sharma: So, in Slaves for Peanuts, you trace the arrival of the peanut in West Africa, how it gets incorporated into local culture, and eventually, how it becomes a cash crop grown to satisfy demands from America and Europe, and, for a time, is cultivated by enslaved labor on the continent.

Jori Lewis: Yes. The peanut is not native to Africa. It’s from South America. Its presence in Africa is thanks to the Columbian Exchange, as they say, just like tomatoes and potatoes and corn and such [The Columbian Exchange refers to the mass transfer of goods, plants, populations, diseases, and ideas between the so-called New World and the Old World following Christopher Columbus’s 1492 voyage]. So, the peanut spread across the continent. And people in West Africa, probably all of Africa, were growing peanuts in their kitchen gardens, and used them for sauces or to accompany their meals. This is pre-capitalism.

Then, as time goes on, markets develop in the United States for peanuts for what they called confectionery—sugared peanuts, roasted peanuts for ball games, circuses, and theater halls, that kind of thing. Then there is demand for peanuts for the soap industry in France. And later, peanut oil becomes a table oil, used for all kinds of things.

And that demand really changes the face of how the peanut is cultivated in Senegal and other places, and drives a number of social changes, including the demand for labor.

Formal colonialism at this point hasn’t started yet, really. It starts much later than we think it does. But the French and other European powers have long been practicing a kind of mercantile colonialism—colonialism by capitalist proxy. And the peanut becomes integral to that enterprise, eventually driving French expansion.

Meara Sharma: Yes, you detail in the book how the demand for peanuts drives the French into Senegalese lands. But you also focus on colonial influence via religion. And much of this part of the story is told through the eyes of Walter Taylor, a black man from Sierra Leone who is employed by the French to work for an evangelical Protestant mission in St. Louis, Senegal. Through him, you’re able to explore the legacy of slavery in Senegal, because his mission becomes a refuge for runaway slaves. How did you come to this character?

Jori Lewis: So, when I first started this book, I started with the big concept. I was interested in peanuts and their relationship to slavery in Senegal. But right when I got my contract and started to research, Senegal’s archives—which are the archives for all of French West Africa—closed. It was meant to be for a few months, but it ended up taking some 20 months. So West African historians the world over were just crying. I couldn’t do some of the research I had intended to do.

I always credit this historian, Hillary Jones, who’d written a book about Senegal. She had a reference to a Protestant mission for runaway slaves. And I was like, “The hell?” I never imagined that I would find a story about runaway slaves in Africa. She cited some dispatches from missionaries, some reports and the like. So again, this is just my desperation. I was trying to figure out how to get access to primary sources, the primary documents that you really need to write a narrative.

And so I decided to go to Paris to see what other documents the Protestant missionary society might have. And in fact, there were about 20 years of letters between this Black Sierra Leonean missionary, Walter Taylor, and his director in Paris.

That’s where I started to realize that I could build Walter Taylor out as a character. I’m not a historian. I am a writer, a journalist, and I don’t have historian goals. Historians are trying to further an argument about a thing. But my goal was to tell a story in the most engaging way. And the best way to tell a story is through the eyes of a person, really.

And for me, Walter Taylor was one way into the story about slavery since he was an advocate for runaway slaves and the newly liberated. It’s hard to find stories from the enslaved directly. There are very few slave narratives coming from the continent. In the United States and the UK there are lots, thanks to the abolitionist movement, but there aren’t so many from this part of Africa.

Meara Sharma: You mean former slaves writing their own testimony, life history?

Jori Lewis: Yes. I wanted to have the voices of enslaved peoples, but it was incredibly difficult to find. So Walter Taylor’s journey almost stands in for them. And it works, too, because he was also a descendant of enslaved people.

Meara Sharma: His parents were destined to be slaves in the New World, but were actually freed directly from a Portuguese slave ship and taken to Sierra Leone to be part of the British abolitionist community of Freetown. So Taylor is born into this cadre of “liberated Africans” who are able to get a western education and become leaders in society to some degree. And then he winds up running this mission in Saint Louis. He has a strong social justice instinct—he’s helping runaway slaves. But he’s also part of this civilizing mission via religion and often has a very patronizing attitude toward local culture. So it’s quite a kind of interesting mix of characteristics.

Jori Lewis: Yeah, absolutely. Again, because I’m bound by the archive, I would have loved to have seen other letters that Walter Taylor wrote to his friends or family, but I could only see what he was writing to his French benefactors.

Who knows what he might have said among his peers. But I think from the few morsels we get, you can see that he was someone who was very savvy in negotiating things. He seemed to know what to say to what audience.

Meara Sharma: Yes. On the one hand he says, about the Senegalese locals, “these people need to be saved,” and whatnot. But on the other hand, when, for example, one of his students goes to France to study and then comes back, he delightedly says to his director, “Your civilization has not dazzled him.” I thought that was a great quote.

Jori Lewis: Yeah, I did, too. It speaks to this larger question about “respectability.” It’s a very old-school idea, but back in the civil rights movement, people were saying, “Well, we have to be a certain way so that mainstream society will take us seriously.”

And I think that’s very much the perspective of Walter Taylor. So even while he is telling people in France and Switzerland that the Black man doesn’t need to give up his clothing, his habits, and the way he eats, he’s telling his proteges and the formerly enslaved people in his mission, “Yes, you should wear coats and vests. Yes, you should eat in a certain way. Yes, you should decorate your house a certain way.” You know what I mean? There’s a kind of double talk.

His way of being and navigating the world seemed similar even to relatives of mine. Maybe that’s also why his story resonated with me so deeply, because it reminds me of my family. My parents are very religious as well.

My grandfather’s grandfather was born enslaved. That’s not so far back. So to think about how, from that enslaved grandfather to my own father who grew up under Jim Crow, they moved within a society that wasn’t set up for them, that was trying to make them fail. And, of course, they developed this kind of obsession with respectability and fitting in to get ahead, but knowing that you’re not really on board with what those people are saying. That was recognizable to me in Taylor’s behavior.

Meara Sharma: Another really interesting part of this whole story is your discussion of the shades of slavery and the shades of freedom that existed in Senegal in this time of shifting policies and French influence.

Jori Lewis: Most of us have an America-centric understanding of slavery. But in Africa, and I think even in parts of the Americas, there were many ways of living as an enslaved person. And different types of slavery. I think we tend to collapse it into one story.

In the US, what we had is racialized slavery. Whereas everybody’s Black in Africa, so it’s more complex. People who were enslaved usually came from somewhere else, maybe had been caught in a war. It was often possible to buy your freedom over time, and to integrate into society, to a degree. It was possible to buy your freedom in the United States of America, too, but was less common. And, of course, we had our problems with integration.

In the part of Africa that I write about, many of the societies are hierarchical, with a lot of different categories of people, of castes. Work-based categories. And among the enslaved, there were also different categories of enslavement. There is a category, for instance, that translates to “house slaves” and indicates people who are born into slavery. Typically these people cannot be sold. And their relationship to their enslaver took on a flavor of kinship. And then there were “trade slaves,” typically people who had been freshly caught and could be exchanged for goods like horses, salt, bars of iron, and the like. So that’s part of the discussion I have on slavery.

I ask the reader and myself about what freedom might mean in this context. What does freedom mean if you can’t support yourself? What does freedom mean if you don’t have access to land, or access to food, or access to jobs, or access to marriage? It’s not like, “You’re free,” and that’s great. People needed social services and help. And that’s another way that Walter Taylor plays a role in the story.

Meara Sharma: On a similarly counterintuitive note, the abolition of slavery on French lands coincides with French expansionism and colonialism.

Jori Lewis: The 1848 abolition of slavery on French lands happens at an incredibly chaotic time for France. A Republican—as opposed to royalist—government has come and they’re trying to implement the ideals of the French revolution and that inconvenient motto: “liberté, égalité, fraternité.” So how can you be a country that has this motto and you enslave people? They’re maybe conscious of this hypocrisy.

But then the political part of it is trying to minimize the impact of abolition on its colonial outposts in Africa, where local forms of slavery might exist. From a tactical perspective, the French are trying to understand how they can maintain the few holdings they had. How do they keep the land safe for commerce? And how do they slowly extend their influence and control through treaties, trade relationships, contractual relationships—which may mean turning a blind eye to slavery in these areas.

So the book tries to explore this push and pull between these broad, beautiful ideas about humanity and what people on the ground are actually doing.

But is being a free laborer enough, if you’re forced through your economic circumstances to indebt yourself, or live hand to mouth, or work as a sharecropper with no hope of getting out from under that yoke?

Meara Sharma: At the same time, abolition also serves as a justification for colonialism. Can you explain?

Jori Lewis: Sure, that is something that develops a bit later, towards the end of the century as formal colonialism is starting. When European powers met at the Conference of Berlin in the 1880s to carve up Africa amongst themselves, they said they wanted to bring an end to slavery in Africa. Effectively, this new push for abolition was used as an excuse for European occupation. In the book, I try to show how the activities of the French administration in Senegal reveal to us that their actual interest in abolition was situational at best. And, obviously, we know now that Europeans were fond of coercive labor systems for their subjects. I remember seeing a letter from a French merchant during this period or maybe at the turn of the century, and he says that there may be “captives” on some farms in the area, but really, it’s not so bad because the people must be forced to work.

Meara Sharma: This is picking up on much older ideas about the “benefits” of slave labor versus free labor, and the relationship between anti-slavery and capitalism.

Jori Lewis: Yes, there was in the late 18th century this idea that free-market labor instead of slavery was ultimately better for everyone. Capitalist abolitionists were trying to counter long standing racist discourses that justified slavery since, it was said, black people were lazy and that’s why Europeans have to force them to work by enslaving them. The free labor people are saying, no, free labor enhances the moral standing of the individual who engages in it, so it will help the “degraded” increase their moral standing. So there’s this whole strange layer of moral uplift attached to choosing to work instead of being forced to work.

Meara Sharma: Right. In addition to this notion that people will work harder if they’re getting paid a small amount rather than being forced to work and be dependent under a system of slavery.

Jori Lewis: Yes. And it goes back to this idea of gradations. I think we have a tendency to say, “This is right. This is wrong.” With free labor versus slave labor—obviously slavery’s wrong. But is being a free laborer enough, if you’re forced through your economic circumstances to indebt yourself, or live hand to mouth, or work as a sharecropper with no hope of getting out from under that yoke?

Meara Sharma: That’s a kind of slavery, too, is it?

Jori Lewis: Exactly. So I’m trying often in this book to really explore the various shades of grey that are present in this whole conversation. There’s a triumphant narrative. Slavery until freedom. But freedom wasn’t great for everyone, and it still isn’t. We have to sit with all those contradictions.

Meara Sharma: Another important strand of the book involves a very different historical character, Lat Joor. He’s a 19th century damel—a sovereign or King—who reigned over an area that became a peanut hub. He resisted French control for years and fought tooth and nail to retain his autonomy.

Jori Lewis: Yeah. In addition to wanting to tell the stories of enslaved people, I also wanted to write history from a perspective other than that of the colonizers. Lat Joor is a towering figure in Senegalese history. He’s basically Senegal’s George Washington. For years, the French sort of vilified him, but in post-independence in Senegal, there was this attempt to recover his story, among others, as a national hero. And we might question that—because he was a complicated individual. But his story is full of emotion and drama.

There are a number of these kinds of figures who battled colonialism. But the stories, when you dig down a little bit deeper, are not as straightforward as they might seem. At my book event in Dakar, this Senegalese historian thanked me for “telling the truth” about Lat Joor. He praised a quote I included where Lat Joor calls the news of his nephew’s death—a rival of his—sweeter than honey. The historian felt it was important for people to know about these elements as well as the grand anti-colonial resistance elements.

Meara Sharma: There was infighting as well. There always is.

Jori Lewis: Exactly. So there is a kind of movement to recognize history as it is. To recognize the complexities because history in the hands of governments, especially, becomes about promoting a single narrative. A narrative of triumph. When it’s not always that simple.

But telling Lat Joor’s story is important for another reason, in the context of how we write African history. Part of my goal was to bring a kind of dramatic treatment to, at least, this part of African history. He’s like Macbeth. You know what I mean? It’s high tragedy.

And I don’t think we have a tendency to understand, or to appreciate, these African stories in that way. So that they’re not just seen as African stories, or just for people interested in Africa.

Meara Sharma: Right. It can be interesting history, interesting characters, full stop.

Jori Lewis: Yeah. Why do we all read Macbeth? Do we all need to know about Scottish history? Right? So, it’s about broadening our common language and our common references.