Art by Osheen Siva

Art by Osheen Siva

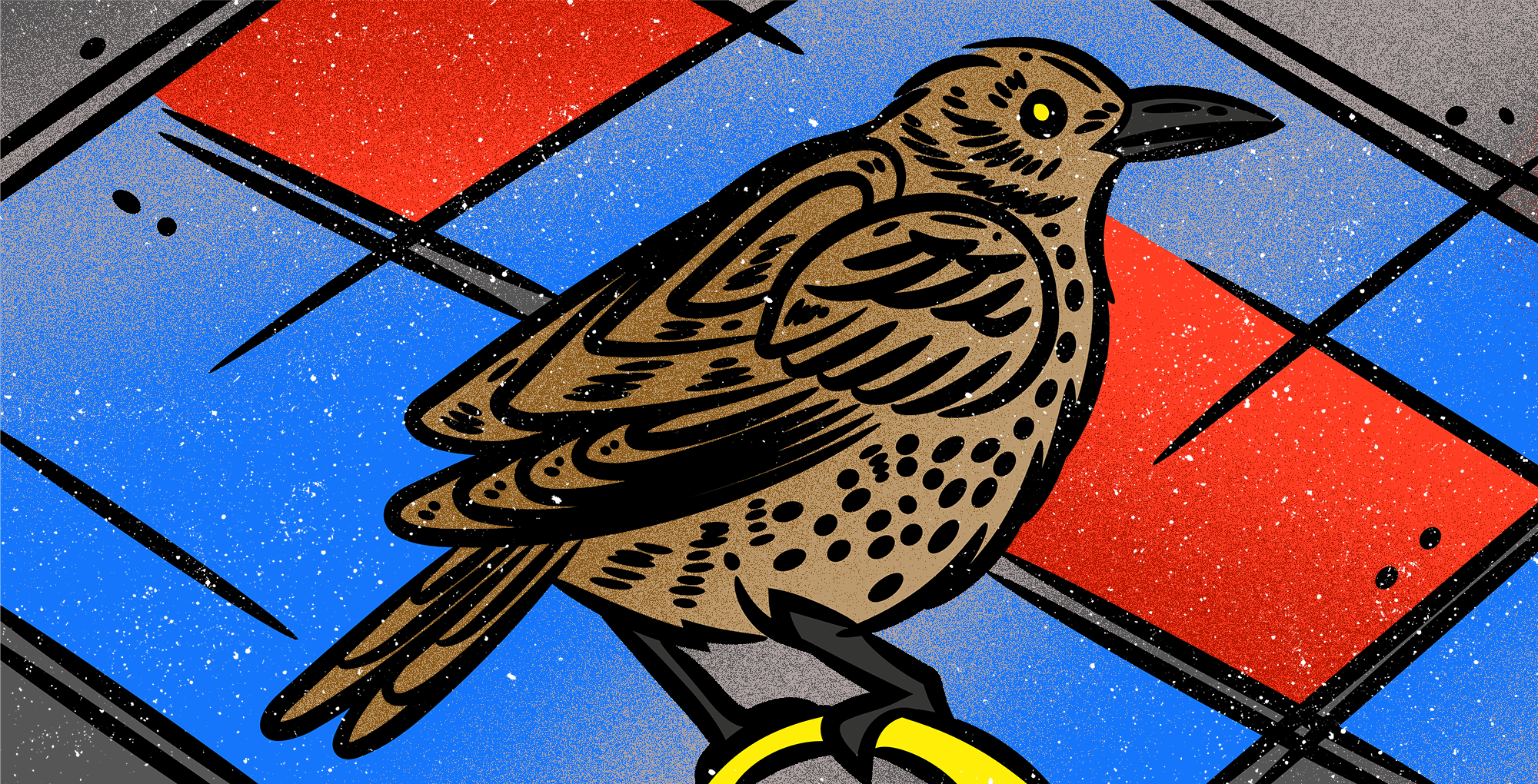

Something feathered dropped through the opened window. Acen scanned the black spots on its chest, the short fan of brown tail feathers, the orange of its lower beak. Acen should ask Box about this bird. Box, the speaker set in the wall of Acen’s prison cell, would answer any question Acen asked it. Unless it involved what he most wanted to know: what day, month, season, or year it was.

Acen understood that the tribunal didn’t have any choice in his initial sentence. As the lead negotiator in failed peace talks, Acen received the mandated punishment: confinement for however long the war itself lasted. But then they discovered his other crime, his decision to care about the wrong thing. It was an act that resulted in a much harsher sentence.

The bird hopped closer, showing black-blue eyes. Acen leaned off his bed-chair to get a better look. Acen could not reach his single blacked-out window, which seemed to open on some nights and not others, following no discernible pattern. Was this bird an accidental arrival? If it was, was the sleeping gas coming next? Would Acen wake up and find the bird gone?

When Acen’s keepers needed to, they put him out with the gas, then cleaned his teeth or drew blood before placing him back in his cell, which was about 15 by 20 feet, just long enough to pace. Since the day the tribunal re-sentenced him and moved him to this unnamed location, Acen had not seen or heard another living thing. Until this bird appeared.

The bird was no bigger than the fingers of one hand bunched together. It seemed to tumble in through the window. Did that mean it was still learning to fly? Acen regretted not paying much attention to birds in his former life. It would be nice to know something like that without asking Box.

After the war (“Acen’s War,” as it would always be called by his side) started, the authorities had followed their usual protocol, searching the records of his failed negotiating team in order to help the next team’s chances. That’s when they found out that Acen had asked to move the smallest line on the map without ever explaining the request.

It had happened after a dead soldier’s mother contacted Acen. Her son had fallen on the wrong side of the line in the prior conflict, in the territory of a faction that returned living prisoners but not the remains of an enemy. If Acen got the line moved a bit, she could retrieve her only son’s body. Acen should have told the woman no and documented his refusal. He found himself sitting and staring at just such a message, one he never sent.

Acen’s acceptance of the mother’s request, of choosing solace for one person instead of focusing on the hopes of the many, was seen as a crime even worse than failing to secure peace. Acen openly admitted to this second crime when he was confronted.

No extra length was added to his sentence. Instead, his additional punishment was to be isolated from all markers of time passing. Like everyone else suffering through the war, he would wait for it to end but, unlike them, he would not know how long he had waited. Never know the first sunrise of a ceasefire, or witness the turning of the page from conflict to peace.

The bird took a long drink from Acen’s water dispenser. Acen hoped that some of it would trickle onto the floor, so he could touch it and be sure of the bird’s actual presence. But it drank with avian grace, not losing a drop as Acen weighed what to ask Box about it.

Acen asked Box a lot of questions, trying to trick it into revealing something about even just what month or year it was. He used both ancient and advanced techniques. Knowing that seeking the position of a star from a fixed point on the planet was too direct, Acen asked instead about the present distance of several planets from the sun. Box gave him two of the four data points Acen needed to estimate the time of year, and then declined to provide the last two.

So Acen had learned to be indirect in his initial question. Instead of asking Box to confirm the existence of the bird in his cell, he said, “Box, what kind of birds are present outside this facility?”

The soft voice, like a teacher talking to a child who was trying not to cry, responded.

“I can’t answer questions about anything near this facility. I’m sorry.”

Box was always sorry. Always polite. It never reacted to Acen’s profanity or to his pleading. Incapable of conversation, it would only answer questions or play the music he requested. Denial of music was considered too terrible a punishment, even for someone like Acen. He had even tried using the music to tell time, ordering Box to play a symphony that Acen knew to be one hour long. Box played it. Acen asked Box to play the song over and over until he realized he would drive himself insane if he listened to that particular staccato again. Now, Acen changed his tactics and said, “Box, why is there a bird in my cell?”

“There are many types of birds in the world, prisoner.”

Acen refused to let Box call him by his name, refused to allow the pretense of forming a real relationship. No matter how many times the AI said it would be nice to learn his name. As if it did not already know.

The bird walked across the cell. It lifted its head, tilted its bill, and began to sing. A trio of deep notes, then one going higher, a tenor’s reach. The trio repeated. Acen closed his eyes and imagined hearing that sound outside, imagined being outside. He saw himself sitting on a grassy hillock, looking up to see small wings beating, then steadying into an arc, the bird rising into a column of warming air.

After 27 seconds (Acen could count seconds, a triumph over the system, however small) the bird stopped singing. Acen watched as it turned toward the tray holding the remains of his… what? Morning, mid-day and evening meals were measurements of time so the three meals that arrived through a slot in the wall were all the same thing: an undifferentiated pile of nutrition pellets.

Then the bird flew out the window. The window shut behind it.

When Acen woke up again, his window was still closed. Acen said, “Box, is the bird coming back?”

“There is no one here other than you.”

“It’s good to know I have your undivided love and attention, Box.”

Acen returned to his pre-bird quest: learn how much time had passed. His prior attempts at manual timekeeping, such as tearing strips off his bedding, had always resulted in the sleeping gas. Acen would wake to find his creativity thwarted, with the offending item removed and replaced with something impractical for the marking of time. On this attempt, he started with inquiries into the location of animals with long-distance annual migrations, hoping to get a sense of what season it was. Acen said, “Box, which direction are the antelope of the Great Coastal Plains going?”

Box said, “There are several thousand antelope in that herd.” Acen asked which way the lead antelope was headed. Box told him how fast antelope could run.

Acen tried three other species and their patterns: an Arctic bird, a whale, and a bat. Instead of answering his questions, Box described each species’ traits in numbing detail. Acen did not need to know how bats use their sense of smell to find a mate, how much a blue whale weighs, or why northern birds don’t freeze to death.

Acen then tried the level of lakes affected most by melting snowpack, the cost of electricity in cities that used more energy in the summer, even the commercial availability of a certain type of berry that only grew in the wild during the late summer. None of that worked.

Two waking cycles later, the system had opened the window again. Acen had taken to stripping his simple blue tunic off before going to sleep in the hopes that any cool air might wake him and he might hear the bird nearby outside. He lay under the window now, his arms curled around his blanket, looking up.

The bird arrived just as the lights began to come up in his cell. It balanced itself on the slanted ledge of the ten-foot-high window, not coming inside the bone grey walls of Acen’s cell. Then it dropped past him toward the shorter wall on Acen’s left, the one where the food pellets and water had been. But there was no food or water tray yet. The bird walked around for a bit, stopping five feet from where Acen now stood. It began to preen itself.

Acen jumped, trying to grab for the bird. He’d spent the prior light periods practicing, making quick moves to the side, having Box play fast paced music as he did. He planned it out carefully. Still, if he missed, would the bird be afraid of him? Would it never come here again? Even if he got it, would they let Acen keep the bird? Worst of all, what if he injured the bird? But Acen needed to know this, this one possible reality.

Just as Acen leaped, the food tray appeared through the usual slot on the floor. Acen tripped over it and fell face first toward the floor. He caught his fall but missed the bird. Now the bird was in the opposite corner nearer to Acen’s chair. The bird stayed still as Acen went over to the food tray. Acen took a handful of pellets. He made a trail of them from the other corner back to the tray and sat down two feet from it. Acen said, “Well, how shall we negotiate this, bird?”

The bird skipped along the trail of pellets. It took one, then spit it out. Acen said, “Good call, bird. But you get used to that vague hint of nothing.”

The bird relented, flew hopped over to the tray, climbed on it, took some pellets, ate a few, then took a long drink of water. Acen said, “Box, should I still eat what the bird landed in? I know you want me to be healthy.”

Box said, “Your food contains adequate nutrients.”

Adequate nutrients. And all the health care Acen needed to ensure he did not escape punishment through an early death. Early on, Acen had asked Box how many other windows there were, tried to get some sense of the number of the other prisoners. That information was politely denied. And Acen’s walls gave way like sponges when he tried to push on them, tried to tap a message in prisoners’ code to any others here. To reach someone. Anyone.

The bird bounced sideways toward the window. Its wings were little and must be so fragile, thought Acen. The window started to close just as the bird took flight. It circled back in just before the closing edges might have caught its feet.

The bird settled on the far edge of Acen’s chair, just out of easy reach. Acen stayed awake while the bird rested, watching it, his own eyes not quite closing, waiting for the bird to rise and sing again.

Acen was awake for five meal cycles. Ones that he and the bird shared now that Acen had decided not to risk grabbing the bird again. Acen watched the cobalt spot on the bird’s neck moving as it swallowed pellets. Watched the way its head shifted up as it was about to start singing. When it wasn’t singing, Acen told it about his life, about his birthplace, a location bargained away by his predecessors when he was ten, about his brother’s death in a war when Acen was 20, of the pride his own mother felt when he was named a lead peace negotiator. Then Acen’s eyes gave out.

Acen woke to an open window and no bird. There was the food tray with its usual portion. The window did not open again for many cycles. Acen decided to try to get their attention, get them to give him back the bird. When the food tray arrived, Acen took all the pellets and flushed them down his toilet. Acen did this over and over, managing not to eat for thirteen waking cycles. Each time he flushed the pellets he asked Box to bring back the bird. Each time Box began another avian natural history lesson. When an acorn woodpecker dies, other woodpeckers form coalitions and fight murderous multi-day battles to gain control of the dead bird’s turf. The battles even draw crowds of woodpecker spectators.

Though feeling faint, Acen sat up when the window finally opened. The bird flew in, winging around at about six feet high and landing near the tray, only to find it empty. Acen dropped his head into his hands. He said, “I’m sorry, bird. Please. There will be more food. Please.”

The bird flew out the window before he could finish the second please.

After that, Acen kept a few pellets from each tray, flushing them when he accumulated too many. But it grew harder not to eat, his lizard brain’s claws grabbing hold in his head, his stomach’s disgust at him growing.

Acen thought he made it through five more cycles without eating anything, but it was hard to keep track only in his head. Acen said, “Box, how long does it take a man to starve to death?”

“If the man has drinking water, it can take months.”

“Box, if I die before the war ends…” Acen paused himself, thinking two could play this game.

Box responded before Acen could finish, saying “I cannot give you information about the war. I’m sorry.”

Acen said, “The rest of my question was: ‘Who will take care of the bird?’”

Box didn’t answer. Acen managed to keep up his battle with famishment for two more cycles. Then he woke in the cloudy way he always did after they gassed him. His stomach did not pang and his tongue felt normal again. He even felt like he had gained a couple of pounds. Acen said, “Box, bring back the bird.”

“I need you to form a question.”

“Box, is the bird gone for good?”

“There are many species of birds in the world. Would you like to know more about them?”

Acen began eating again, always keeping a few spare pellets at hand just in case. He stopped asking to hear music, stopped asking Box any questions, just sat on the bed between meals for cycle after cycle. Finally, the window opened again. Acen waited but nothing came in. At some point, the window shut again without any sign of the bird. Acen spoke for the first time in… he of course did not know how long, his own voice now foreign to him, an animal’s croak. Acen said, “Box, you have to play any music I want, correct?”

Box said, “I have a wide variety of music available for you.”

Acen said, “And you have to play whatever I request?”

“Yes.”

“Box, play something loud. Something with a lot of percussion. Wait, first, Box, tell me, whose bones are denser, humans or birds?”

Box said, “In general, bird bones, although sometimes hollow, are denser than human bones.”

Acen waited for a heart-pounding drum section. He cocked his right arm, then slammed it against the only hard object in his cell, the toilet. He did it over and over until he was sure bones were broken. Then Acen set in on his cocked left arm until he felt the ulna, then the radius cracking. Let them see now that he was broken enough not to fly, he thought.

When he woke up, the toilet had been replaced by one made of a rubber-like substance, complete with a recessed flush button. His arms were fully healed.

Acen knew he could give up on the bird. Focus on hope alone, hope that the lead negotiator who followed him was better than he was. Try to forget all the lines he remembered so well. The ones on the maps, the ones on the face of the dead boy’s mother.

Or he could again try his abstract list of natural phenomena, try to fool Box into revealing some small detail about how much time was passing. Keep asking questions that would be recorded and analyzed by someone, someday, for some purpose. Forget about the under layer of the wingtips, the semicircle of the short bill, the way the shining eyes shifted as it stood stock still. Forget the bird.

Some days he could. Some days he could not.

So Acen took to doing only two things. When the lights went out, he was lying by the window, stripped down, waiting. And when the lights came on again, he was working on the new task he had set for himself.

*

The cool air woke him up. The bird stood on the open ledge of the window peering down at Acen. Acen smiled, then took a deep breath, thinking about this new question he was about to ask Box. One that he had waited to pose until the bird’s return.

The work leading up to it had taken up all of Acen’s awake cycles. He had started by whistling what he could recall, asking Box to identify possible bird families. Then Acen asked Box things like, “Which of those birds have black spots that fade as you go down the belly?” and “Which of that species have a ruddy brown crown?” and “Which ones have feet the color of pink sea stars?”

Acen was almost sure he had found it, found the right one. He was sure he had done the best he could with what he had available. And he could live with that, could live with this effort to learn some fragment about when it was now, to make someone recognize him no matter how long it took.

Acen woke. The bird was sitting on the edge of the window. Acen slid back onto the floor, then stood up slowly, raising and opening his left hand, watching as the bird shifted from one foot to the other, its fine head going under the left wing and then popping out again. It did not move from the window ledge as Acen asked Box his new question. “Box, is birdsong music?”

The speaker did not respond. Acen’s chin dropped and in a wheeze he said, “Box?”

Then Box said, “Yes. Birdsong is music.”

Acen said, “Box, play the mating season song of the Quaker’s Thrush. Softly.”

A song began. A melody that started when the earliest pink cherry blossoms began scattering in a spring rain and that stopped when those same trees were bare of their flowers again, now green again; its first notes a ravine, then a steep rise. From its perch on the window ledge the bird’s eyes shifted around the cell, seeking the source of this unexpected echo of itself, looking for where to direct what Acen hoped would be its instinctive response. Then the bird lifted its head and tilted its bill.

And Acen waited.