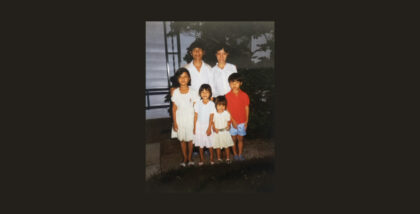

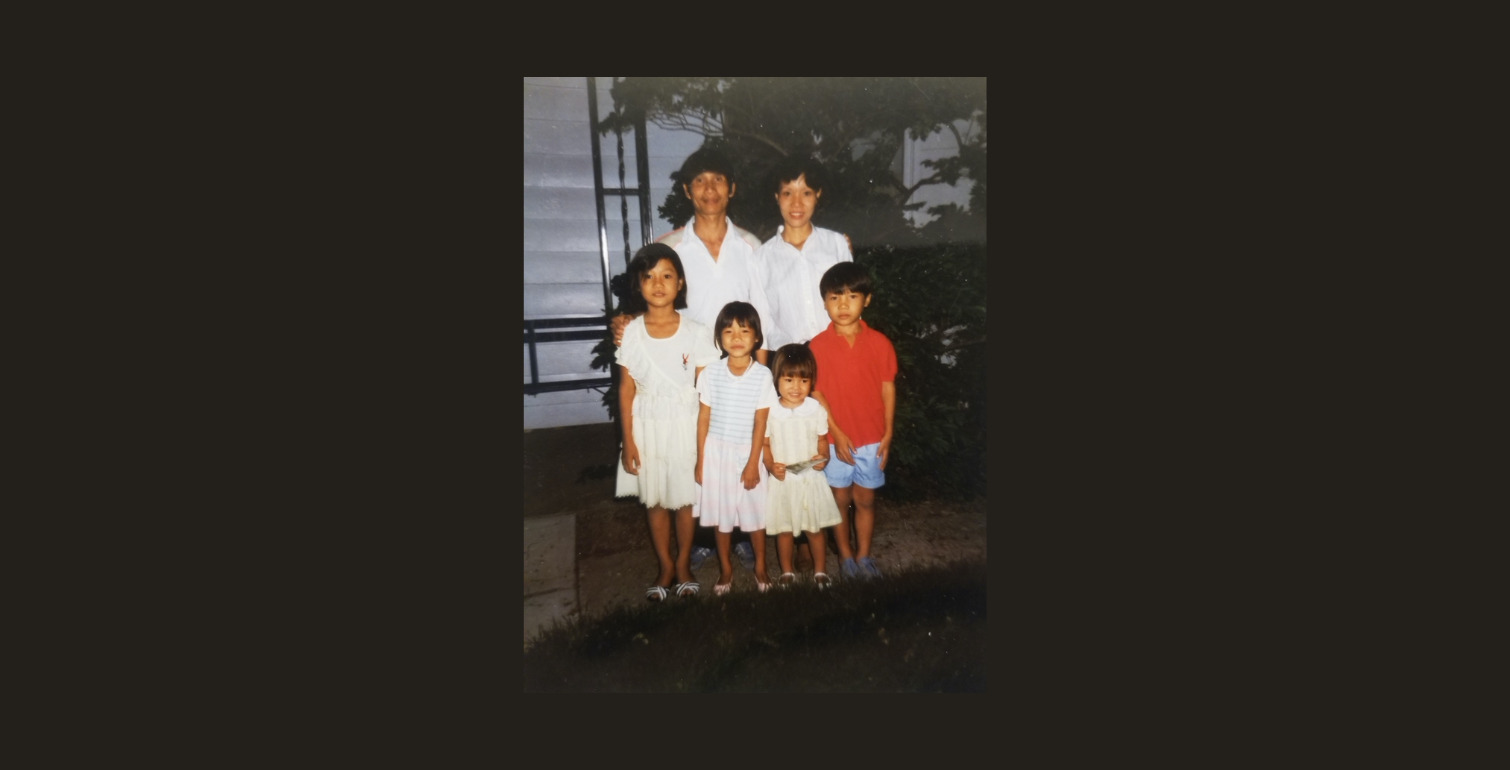

All of us, my family that is, are standing in front of a motel in Coralville, Iowa. The first ten of our days in the United States were spent in a motel. Who paid for those ten days? For the longest time, I thought it was a gift from the US Government. I thought they were apologizing because they felt bad for us. “I am sorry for that war. Stay here for what we have cost your entire country. Sorry we pulled out of the war too late or too early. Sorry we got involved. Sorry some of you got blown apart, mutilated, tortured, drowned, raped by pirates—your lives stolen, your family split apart across the world. Please accept your ten-day hotel stay on us.”

None of that. What I have learned most from life is that nothing is ever free. Everything has a cost. Years later, I learned that my father paid the government or church who sponsored us back. He paid everything back: the cost of six international flights from the Philippines to Cedar Rapids, Iowa and our ten days at this motel. He worked almost 30 years at a car manufacturer to pay for our freedom. He and my hardworking mother paid such a price. If there is something to say about my diligent father it would be that he is extraordinarily good at paying off debts. In this photo, perhaps you can tell, his face is a debt-free face. The house he currently owns in Iowa City is completely paid off, paid with cash. My father doesn’t owe anyone or anything. He is one of the freest humans in the United States, fiscally speaking. He doesn’t have any credit card debts. No car payments. He pays his taxes a year ahead. If he could, he would pay everything, including his life, ahead. I may have acquired this from him.

But this freedom from debt enslaves my father. It’s like washing one’s hands obsessively. My father washes his debt hands until they’re dry and then bleed. And, then he douses the dryness with lotion to diminish the discomfort. I also wash my hands of debt and I am as desiccated as the deserts in Vegas that I love. I do this by paying all my medical bills, my health insurance bill, water bill, internet bill, and even my mortgage bill a month or two ahead. The cost of this freedom from debt is a return to prison. A return to the concentration camps where the communists fed my father water spinach.

I cope with this debt-free illusion by turning to suicide for comfort. I am sure my father did as well. To end his relationship with suffering and debt. I am sure he tried to die numerous times. The cost of debt freedom is continuance or rather discontinuance from life. I tried to end my life in New York. In Las Vegas. Each time, the love I have for my mother and my best friend stopped me from finishing. But if I were truly free, I would have died a long time ago. It’s the only way to claim back the debt America owes me. True freedom would be no longer signing an existential lease—no longer remaining among “earth’s inmates,” as Frank Bidart wrote.

I call this debt-free space: the autoimmune disorder of the psyche.

I am hoping to find another photo where we are happy together. I am almost fooled by this one, until I see my brother’s face. His face holds so much sadness. His red shirt holds all the pain. Even down to his shoes and shorts, they are blue like Picasso blue, while the rest of us are dressed in the color of light and contentment and elation. I love this photo of my two little sisters, U and VA. They both look like they walked out of an evangelical pamphlet, the kind we often received from fundamentalist Christians handing them out door-to-door, their faces like the Elysian Fields, paradisal bliss. I am just my usual self, in a dress meant for me. Some of my hair is falling over my face. There is no trace of the fever that led my mother to perform cạo gió, to scrape the wind out of me. I am a Vietnamese girl again, with my father’s assured hand pressed against the right side of my shoulder, gently and caringly.

Both my parents are dressed in radiant white, the color of death. Of ghosts. I love both of their facial expressions. These are the faces of folks who are not marred by hardships, stress, anxiety, and the weight of the brutal American system that values independence over family, wealth over intimacy, work over leisure. The system where everything was against us. In this photo, injustice and racism and prejudice haven’t broken the spine of our spirit. My mother, despite her tiredness here, looks gracefully happy. My father’s hand is around her, in the same gentle manner as he has placed his hand on mine. Despite my brother’s melancholic face, we functioned well as a unit then. A unit of love.