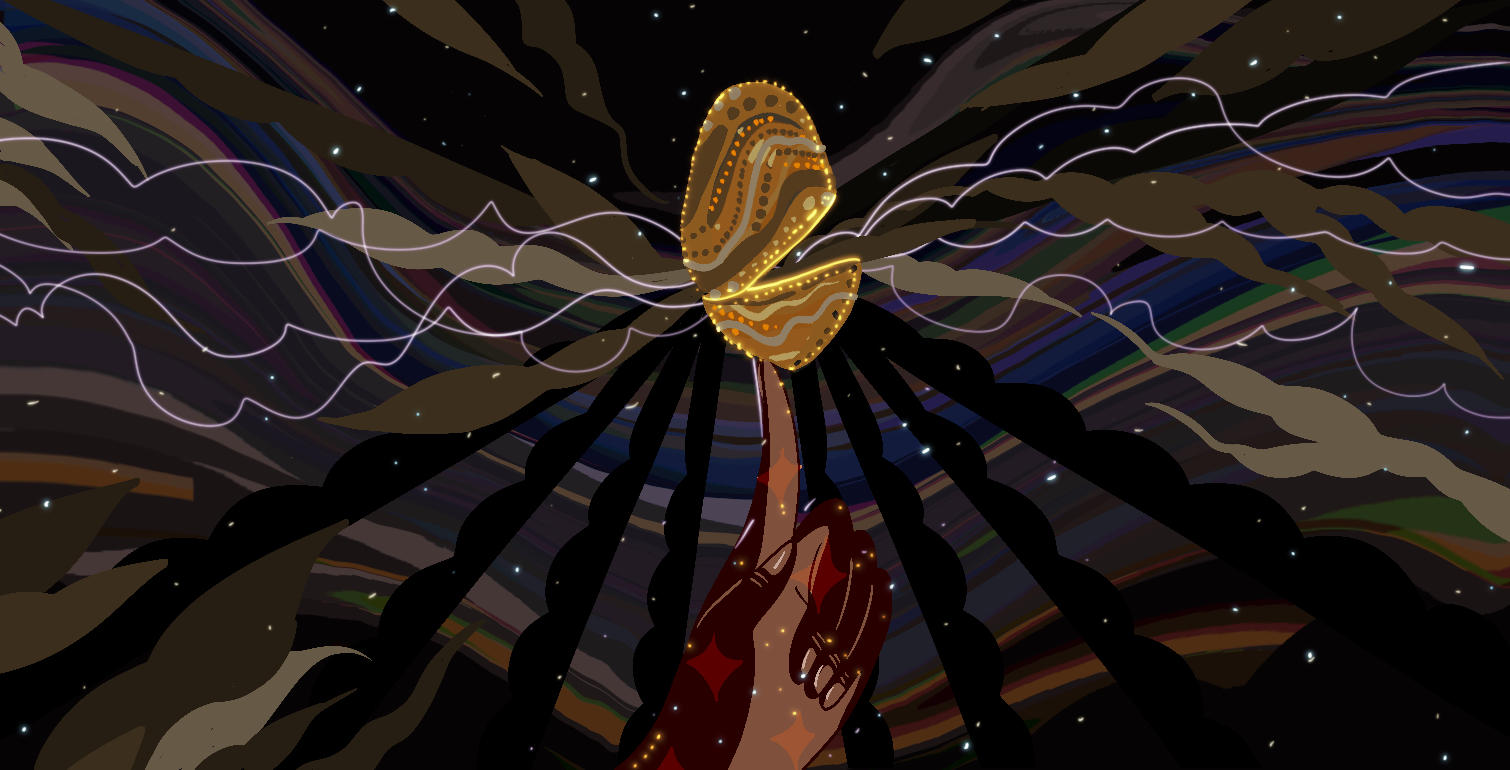

Art by Sab Meynert

Art by Sab Meynert

I’m honestly not sure how my clients find me. There must be some kind of network where they trade the names of mediums and such supernatural types. Normally, I’m going about my life, and they just show up. I mean, I was pricing tomatoes at the market when the environmentalist approached me.

To be fair, unlike my usual clients, he was still alive.

“Adewale Momoh?” asked the skinny man, his Adam’s apple bobbing as he spoke. I eyed him up and down—clean but faded okrika clothes, locally-made leather sandals, an afro and beard so thick that they looked like they would knock him over at any moment. A typical do-gooder type.

I could see he was intimidated by me. Understandable. I am nearly seven feet tall, bald, and built like a Senegalese laamb wrestler. Add all the scars from my time as a soldier in the corporate armies of the climate wars, and I can be frightening if you don’t know me.

“Call me ‘Hungry,’” I told the man, to put him at ease.

He nodded warily. “Samuel Amosu.” We shook hands, my meaty paw engulfing his.

“I would like to discuss something very important,” the thin man continued in a rush. “Is there somewhere we can meet?”

30 minutes later, I had him situated in my room-and-parlour place at Ojota. Perched primly on a settee with a cold drink in hand, Samuel explained why he had contacted me.

Two weeks ago, in the small riverine community of Ajido, just outside of Badagry, unknown gunmen broke into the home of a woman named Kudirat Olayinka and shot her while she slept.

She’d been the head of Samuel’s small environmental NGO, a group known as Save Our Beaches—SOB for short. She was one of the few young people who’d chosen to return home after studying overseas, and she’d taken over from the organization’s previous head.

Kudirat turned out to be a brilliant strategist. Under her leadership, the group began organizing with more cleverness and sophistication. Within a few years, they’d started winning lawsuits against local polluters and drawing media attention. As Samuel talked, I realized that I had actually heard about them. It wasn’t every day that a tiny fishing village dared to stand up against a multinational corporation like Globex Extractive Industries, one of the largest sand miners in the world. Yet, somehow, they’d done exactly that, and even won a reprieve from any mining activities in the community.

Then, suddenly, Kudirat was dead. Local police declared it an armed robbery gone wrong and closed the case. Both Samuel and I knew the truth, though. Globex did not like to lose.

When I was born, at the beginning of the 22nd century, the world was choking under the weight of devastating disasters. Much of it could be traced to its addiction to petroleum and a capitalist system that devoured everything it touched to enrich a small corporate overclass. It took a series of conflicts we came to dub “the climate wars” to free us—from some problems, at least.

About ten years ago, in 2153, the last armistice of the wars was signed. A recovering world focused on solar power as the sole solution to all the damage that had been caused by plastic and petrochemicals. Today, our seas and skies are clearer and, in many ways, we are well on our way to reversing the climate catastrophe that our dependence on petroleum created. But, like any miracle cure, our over-reliance on solar power has had its own side effects.

Most people don’t realize it, but sand is one of the most important raw materials in the world. It is the core of permacrete, the world’s new favorite building material since coal-based tar was banned, and is used in all silicone-based technology, including solar glass. Today, sand miners are the largest and most powerful corporate conglomerates on the planet. And they have solidified their hold on the world’s economy the same way the petrobosses did a century ago, and the way the robber barons of the 19th century did: through bribery and violence.

However, sand, like oil, is finite, and we are quickly running out of it. Having exhausted most land quarries, sand miners have been turning to the water, vacuuming up millions of tonnes of sand from riverbanks, beaches, and the seabed every year.

Multinational sand mining companies like Globex prefer to work in international waters, beyond the jurisdiction of nation-states and corporations. Where mining rights might fall under the eye of a country or a corporation’s land holdings, these multinationals rely on local miners to dredge sand on their behalf.

This is where you find the sand mafias.

By acting as local contractors, the sand mafias keep these smaller operations running smoothly. They also carry out the kind of activities that a multinational might not want to dirty their hands with—anything from forcing children to work as haulers to assaulting and killing anyone who might hinder their profits. Shooting someone who got in their way, like Kudirat—while she was unarmed, and in the dead of the night—was exactly their style. Samuel’s cup shook as he told me what had happened.

Here in the Lagos-Accra megapolis, the competition for sand is cutthroat. Once famous coastal areas like Bar Beach, Tarkwa Bay, and Labadi Beach are now distant memories, and miners are pushing further and further inland.

Ajido Village is one of the last untouched riverfront beaches on the West African coast. For a long time, Samuel explained, a high-level Nigerian corporate bureaucrat protected the place from the rampant mining in the region because his grandmother lived there. But eventually the grandmother died, and in the ever-deadly game of office politics, the corprocrat lost his position. The village immediately became the site of intense bidding among the region’s major sand miners, especially Globex.

For years, Globex executives plied village elders with gifts. Samuel noticed that prominent families would regularly find their homes generously refurbished and their children’s school fees suddenly paid up. But the villagers had seen what happened to their neighbors’ lands once the miners got their way, and most refused to allow the miners into the community. Eventually, Globex got tired of trying to convince the people and decided to use force instead. It began by suing the community under some obscure law, slowly chipping away at surrounding land until the village was half its size. Then it sent in hired thugs to threaten residents. More and more besieged, the villagers tried to fight back, but it wasn’t until Kudirat returned home that they started to win.

“With her gone, there is nobody who can stop Globex from getting what they want,” said Samuel. “Our village elders have already agreed to lease the mining rights; they will sign the papers by the end of the month. We need your help, Mr. Hungry.”

But Kudirat wasn’t gone. I didn’t know how to tell Samuel that he hadn’t come here alone. I’d ducked into the kitchen to fetch myself some water and when I came back, I found her in my chair, with a look of quiet consideration on her face. Like most of the newly-dead, she hadn’t figured out how to alter her appearance yet. She still looked the way she thought of herself in life—slim figure, smooth brown skin, and large serious eyes.

The dead don’t talk to me; I don’t have that power. But they do communicate, and from her look her intent was clear.

“Fine,” I said, more to her than Samuel. “I’ll take the job.”

Kudirat broke into a radiant smile.

*

So, here’s the situation. I’m dead. Have been for about a year. The problem is that no one else knows.

How did it happen? Well, that’s a long story, but I’ll make it short.

One night, I was drunk and crossing a street near the Lekki Phase 1 Roundabout. You know how the place floods after even a small rain? Well, I was just walking and then, all of a sudden, I fell into a sinkhole. So many of them have been appearing since the beaches disappeared.

As you can imagine, I died instantly. But after that nothing happened. There were no tunnels, no lights, no leaving my body. Nothing. After 12 hours, when the waters receded, I dragged myself out and went home.

The thing is, while I was waiting for death at the bottom of that hole, I came to a realization: I hated my life. In particular, I hated my work as a third-rate security contractor for Globex. Most of the time it was just guarding the flotillas of offshore dredgers from protesting environmentalists. But sometimes armed locals would try to stop us from muddying their waters and destroying fish breeding grounds, and would attack us. Their cheap Russian rifles were nothing against our high-end Israeli weaponry, though.

I never liked these encounters. Sniping at desperate fishermen wasn’t my idea of a fair fight. So, after I died, I quit my job.

Being neither dead nor alive puts me in an awkward position. My body continues to work—my nails and hair grow, I still need to eat, sleep, and shit—but now I also can see those who have passed over. I think it’s a blessing that most living people can’t see the world that they share with the dead. If they could, they would probably never sleep soundly again. Spirits and ghosts are terrifying—even if you’re one of them. Luckily, most of the dead mind their own business and want nothing to do with the living. But there are some—a tiny, tiny few—who do. That’s where I come in.

It turns out that when you’re half-dead you become a channel, and the dead can work through you. It’s a bit like a shaman being possessed by a spirit, but much less glamorous; think puppet operated by a particularly bad puppeteer.

These days, I put my skills to work for ghosts who are looking to fulfill their last wishes among the living. For a fee. After all, even the dead need to eat.

*

A week after contacting me, Samuel and I decided to launch our first operation to drive the sand miners out of Ajido. To make it work I would have to go and live in the village for some time. It wasn’t too difficult to move since I have no family or friends in the megalopolis.

You see, people tend to avoid me. More than my appearance, there’s something about how I seem. I’ve got strange vibes. Those with the ability to sense the spirit world are the most uncomfortable with me. I think part of them knows my secret. So, most of my daily encounters are with people who are no longer people—just a collection of grievances and unfulfilled longings. It’s lonely, but even before I died, I felt like a ghost in my own life.

We arrived at the Badagry train station just as the sun hit its peak, and took an automated keke the rest of the way. It sputtered along for a few hours, following the course of the Ajido river, from which the community takes its name. For centuries, the river, which ran practically parallel to the Atlantic ocean, was the main source of livelihood for people all along its length. But years of dredging its riverbeds for sand had churned up sediment that was clouding the water, suffocating bottom-dwelling creatures, and blocking the sunlight required by underwater vegetation.

What had once been a clear, sparkling waterway was now a gray-green sludge. It was impossible to fish in the river anymore, and it was getting harder to live by it, too. All along the river’s coastline, sand miners had dug up so much ground that they regularly exposed the foundations of waterfront buildings. Many had already collapsed.

But entering Ajido I felt like I had gone back in time. The village had that picturesque quality that people who’ve never stepped outside of the megalopolis imagine rural life to possess. Whitewashed concrete walls and aluminum roofs, white sand paths and clean-swept compounds. And green, green, green, everywhere I looked.

I got the sense that Ajido knew that it could disappear at any moment, so it had to make as much use of its time as it could. With fishing no longer possible in the polluted river, every home had a small business attached to it. There was mat and basket weaving, small goods trading, farming, even coconut carving, a traditional handicraft in the village. But, like many rural communities, Ajido had already been stripped of its most valuable commodity: its young people.

See, the climate wars had exacerbated the fertility crisis across the globe. Centuries of petrochemical contamination of the air, soil, and water had wreaked havoc on human reproductive systems, making it harder for people to conceive children or successfully carry them to term. In richer countries where the number of children being born had been steadily declining for decades, the wars led to a massive population crash. Poorer countries whose populations often skewed younger suddenly found themselves at an unexpected advantage. Today, the competition for young, fertile people is just as fierce as the one for sand, with countries in the Global North offering lucrative relocation packages to young people from the Global South. And once these youth leave, they rarely return.

We stopped by SOB’s head office, one of the few permacrete buildings in the village with a solar roof, and met with its other members. Samuel introduced me as his friend from the city who would be staying with him for a few weeks. It should not have surprised me that Samuel, at nearly 40 years old, was one of the youngest members of staff. To call the SOB crew a group of elders would have been kind; several of them looked nearly ready to join me in the afterlife.

I began to understand why Kudirat was so special.

Samuel and I discussed our strategies with the staff for hours. Finally, as the night deepened, we dispersed, and Samuel led me to his family home where I would be staying.

As we lit oil lamps in the spare room, I asked the question that had been on my mind all evening as we toured the community.

“I have never worked for a living person before. How did you find out about me?” I asked.

Samuel sighed and sank into the guest bed. It was a question he had clearly been expecting, but had hoped to avoid. “Kudirat told me,” he said simply. “She came to me in a dream.”

I looked to the ghost standing in the shadows in a corner of the room. She gave a small, cryptic smile and shrugged.

Samuel continued. “There’s nobody in Ajido that is less than twenty years old. Most of my age mates have moved abroad, or they have gone to the city for work. Only the old people are still here by choice. But Kudirat was different. There was a light in her. She saw a future here, even though there is no one in the next generation to secure it.”

“Ah, you sound as if you have no hope.”

“If I’m honest with you, Mr. Hungry, I don’t. I would have also gone away, but I’m a sickler. Even if I found a wife, how can I even try for a child with these sickle cells? And even if we managed to have a healthy child, what kind of future am I leaving for them? The one that the sand miners have stolen? Am I going to bring a child into this world just so that it can become a worker for one of the sand bosses?” A note of bitterness crept into his voice. “We may be fighting Globex today, but what of tomorrow? Even if we win, another group will just take their place.”

“Then why are you still fighting? Why did you even bring me here?”

“Because that is what Kudirat would have wanted. After everything she did for this village, those old men are just going to hand over our land to Globex, just like that. So, what did she work so hard for?” Samuel spoke angrily; it was the first time I’d seen him show so much emotion. “See, I might not have any hope for this place, but Kudirat did. She was our light, and I will not allow them to kill her and toss her aside as if she meant nothing.”

With that, Samuel wished me good night and left me with only the ghost for company.

*

The next morning, I headed for the closest sand mine. According to Nigerian law, Globex had to identify a local contracting partner to secure a deal with the community. Last night, we’d decided to infiltrate the local sand mafia operation, the one Globex had already singled out. We would try to shut it down from the inside.

I didn’t have to go far. Right across the road from the village’s border, the land had already fallen to the miners. With my background, I easily found work with their security detail. In fact, I’d actually worked for this particular boss, Sami Ajoseh, before. He was a tough nut, but I was confident we could crack him. There are very few among the living who aren’t afraid of the dead, after all.

They had torn up and lush forests and surrounding farmlands to get at the layer of river sand under them. The landscape was now a flat field of churned soil marked by deep craters and giant piles of sand and rock. Diggers rumbled around, loading sand into trucks while workers smashed rocks with hammers. The air smelled of dust and sulphur.

Over the next few days, the SOB team and I started with simple sabotage. I recruited a few local ghosts to work through me, helping me move at inhuman speeds and with abnormal strength. I’d steal vehicle parts and components—batteries, spark plugs, cables, and wires. Or I’d intentionally wreck digging equipment so that whole teams had to shut down, throwing production schedules into chaos. But that proved useless. Sami simply replaced the missing parts and punished the guards who were supposed to oversee the equipment.

So, we moved on to scare tactics. My helper ghosts did very well, making strange noises, moving items, and arranging furniture at impossible angles when no one was looking. But once again, Sami dismissed every report of such happenings and took to firing workers who mentioned anything supernatural.

It would have been easier if Kudirat had helped. Since it was her last wish that we were working to fulfill, anything she did would have the most powerful effect. But she refused to intervene. I didn’t ask why. I knew by now that the dead liked to move at their own pace. The fact that she was still with us meant that she was invested in the outcome. How she would contribute to it would be entirely up to her.

In the meantime, the day of the official signing was getting closer. At each of our planning meetings, Samuel looked increasingly defeated.

“If Kudirat were here, she would have known what to do,” he once said mournfully. I shared a look with the ghost who stood behind him.

Can I tell him?

She shook her head. It wasn’t yet time.

*

Getting Ajido to sign over their mining rights was a huge win for Globex. To celebrate, the company arranged a lavish signing ceremony, complete with a live-streamed media presence, at the brand new Lekki Grand Hotel. With one week left before the event, the SOB team and I decided to step up our efforts.

That’s how, the day before the ceremony, I found myself huddled in the shadows, waiting for Sami Ajoseh to come home.

He lived in one of the older residential estates on Lekki Island, but where most of the houses in the estate still had low walls and intricate detailing, Sami’s house was newer and taller, surrounded by massive walls topped with razor wire. It was one of those oversized monstrosities that spoke of owners with more money than taste.

A brisk evening wind blew in from the sea, picking up the collar of my jacket and ruffling the ends of my untucked shirt. I didn’t bother zipping up though. The cold no longer affected me much. I lit a cigarette, more out of habit than need, and sank a little deeper into the shadows of the alleyway by the compound walls, waiting.

Ten years ago, this would have been beachfront property, but now the back wall looked directly into the Atlantic Ocean. I could hear the waves crashing into it, threatening to surge into the compound. Sami’s car pulled up just as the last rays of sunshine faded from the sky. I shrank back as the headlights skimmed over me, though I probably didn’t need to. Despite my massive size, most people tend to overlook me.

The compound gates opened automatically, and I slipped in behind the car as he drove in. I drew my trusty handgun from the holster under my jacket and, just as he put his keys into the front door, I pointed it at his head.

My instructions were low and quiet. Sami was smart enough not to resist as we walked around the house to the empty one-room servant’s quarters in the back. Here, the roar of the sea was loud enough to drown out any noise he would make. Without shifting the position of the gun, I shackled him to the burglar-proof bars on the room’s only window. This was where things should have ended. Samuel and I only wanted to get him out of the way so that we could enter the signing ceremony tomorrow and disrupt it.

Then Kudirat appeared.

I’ve had several clients whose last wish was to confront their killers. In these cases, for some reason, the ghost is able to manipulate things in both the material world and the spiritual. I’ve never been able to explain why. Each encounter was different, but very few were kind to the killers. Kudirat did not have to speak to tell me that this was the man who killed her. The fact that he could see her told me everything I needed to know.

So, I stepped aside and allowed her to take over.

Being possessed is like sleepwalking. You are aware that your body is acting, but it feels out of your control. At its best, the experience can feel like two spirits in sync, moving together like a practiced machine; at its worst, it’s a constant battle—you against the voice inside your head.

Sami started begging for his life as soon as he saw her. But he didn’t start screaming until she placed my hand to his forehead, and he saw what she had to show him. He was going to be forced to re-experience events from his life, but from the point of view of everyone he had ever hurt. Every theft, every beating, each act of rape and torture, and every single murder.

Look, I spent ten years as a soldier in the corporate armies of the climate wars. I’ve seen things. But Sami was a very bad man and even I couldn’t bear to watch this. Instead, I turned my consciousness inward and went to sleep.

When I woke up several hours later, my body had been carefully laid out on the verandah of the servant’s quarters and Kudirat was nowhere to be found. The only indication that she’d even been there at all was an otherworldly glow that seeped out from under the door. I had no interest in seeing what she’d left of Sami. So, when the glow faded, I found my way out of the compound.

*

The next day, I didn’t bother working my shift at the mining site, though I heard from fellow guards that Sami had failed to show up that morning. Instead, Samuel, the SOBs, and I put on the nondescript uniforms common among low-level corporate employees and headed for the Lekki Grand Hotel.

Located on Eko Atlantic’s main strip, the Lekki Grand had only opened a few months before. Hosting this event was a massive achievement, and its management was determined to see it go off without a hitch. The hotel was a hive of activity, with Globex employees everywhere we looked. A large metal detector screened everyone who came in or out through the hotel’s main entrance. Samuel and the other SOB members pretended to be day staff hired for the event, and I provided cover for them by acting as if I was part of Globex’s security detail. One of the advantages of my “condition” is that few people want to spend any time questioning me, so we were all quickly waved through.

Once inside, Samuel and the others were whisked off to the kitchens where they would be incorporated into the event’s service staff. Meanwhile I was given a communicator and a handheld weapons detector and stationed in front of the doors to the main ballroom, where the signing ceremony was going to be held later that evening.

From my position, I was able to observe the preparations for the ceremony. Globex had spared no expense. From the imported fine-weave ankara cloths that covered the tables, to the menu featuring lab-grown meat and fish, and even the decorations—3D printed on site—everything was top of the line. The money being spent in this room could easily feed the entire population of Ajido for several years.

By late afternoon, the press—bought specially for this event—showed up and began to set up their cameras and streaming feeds. Lesser guests, members of various other sand mafias affiliated with Globex, also began trickling in and finding their seats. But there were no guests from Ajido itself. Except for the three elders who would do the actual signing, members of the community had not been invited.

At six o’clock, the Globex executives started to arrive. Each one made their entrance amid a flurry of flunkies and aides, grandly greeting each other with chummy handshakes and backslaps. I was surprised to note that they were all Nigerians. I had expected that a company that seemed to have no regard for the environment would be run by people who had greener pastures to return to. Knowing that these people were destroying their own homeland made it much worse, I realized. What in their lives had led them to value money over all else?

When everyone had eventually taken their seats, it was time to start. Unobtrusively, I locked the only door to the room.

Most of the schedule was taken up with presentations from nearly every department in the company. All of them showed how nabbing Ajido would improve the company’s bottom line. Standing by the main doors, I endured speech after speech, each more self-serving and congratulatory than the last, until it was time for the Globex CEO to speak.

A portly man with chemically straightened hair slicked into a popular European style, he looked vaguely uncomfortable in the expensive Western suit he wore.

“You are all most welcome to this auspicious event,” he began. “I am sure I speak for all our partners when I say that this collaboration will revolutionize our operations and our production. Our purpose is to provide the clean energy that once pulled our planet from the brink of collapse and now continues to improve people’s lives every day. This event is a product of years of work from every member of our team, and it is this spirit of collaboration that will enable us to achieve our aim: a five billion dollar return on our investment over the next five years.”

He droned on in this manner for another half an hour. Then, mercifully, it was time to officially sign the papers.

A long table had been set up on the stage at the front of the room. On the right side of the table sat the three elders who had agreed to the deal. On the left sat the CEO and his executive committee, nearly 20 of them. Once they were settled down and about to begin the signing process, we acted.

Samuel and another SOB member unfurled a massive banner across the signing stage that read: SAVE OUR BEACHES NOW! The rest of us began noisily protesting the proceedings. The hotel’s security personnel immediately intervened—though with the door locked, they couldn’t get any further support. Still, I saw Samuel taken down by a blow to the head, and his colleague wrestled into a bear hug and dragged off the stage. The rest of the SOBs were getting pummeled left and right.

I rolled up my sleeves and began making my way to the stage to help my friends, easily taking down any attacker who was foolish enough to come at me. That was when Kudirat materialized, hovering several feet above the stage.

I hadn’t expected to see her here. I thought that after confronting the man who had murdered her, she had moved on to wherever ghosts go when they had fulfilled their final tasks. But clearly, she wasn’t finished with her killers just yet, because she was visible to everyone.

The room fell into awed silence.

For a moment Kudirat did nothing. Then, she began to glow.

And glow.

And glow…

Her light was like being plunged into a scalding pool. I could feel my skin, my mind, my very soul scorched clean. I felt the heaviness, the weight—the vast loneliness that had held me fast to this half-life of mine—being eaten away by the relentless purity of her brightness. And then, it was over.

Gasping for breath, I shakily got to my feet and looked around the room. It was chaos. The guests, the press, the hotel’s security thugs, and the company’s executives were gone. In some of their places were squalling babies and small children, wide-eyed and bewildered. But in most of the other spaces, there were only motes of spirit light floating about. Samuel, the SOB members, and I appeared to be the only ones who had been spared this transformation.

Kudirat was also gone. I had the feeling that it was for good this time. I reached out to Samuel and realized my hand no longer had the grey cast of death.

A chubby little boy of about two or three years old toddled up to me. He was still wearing the Globex CEO’s dress shirt.

“Excuse me,” he said, his speech oddly formal. “I think I’m lost.” He began to cry, and I scooped him up and held him close.

The others were also picking up babies and grabbing children by the hand. We had to take them back to Ajido with us before anything happened to them. Luckily, all the electrical equipment in the room had been fried by Kudirat’s light. It would be a while before the world discovered their fate.

We commandeered an empty luxury bus, the one Globex had used to convey the village elders to the hotel, and hustled the little ones onto it. Tucked into one of the back seats with the former Globex CEO napping on my lap, I stared out the window as we drove through the blasted, blighted landscape. For the first time, I felt the warmth of hope flare within me.

I didn’t know what would become of the community—or the company, for that matter. Maybe Samuel was right; maybe some other miner and their mafia would step in to fill Globex’s vacuum. But until then, we all had some new beginnings to work out.