Artwork by Candice Evers

Artwork by Candice Evers

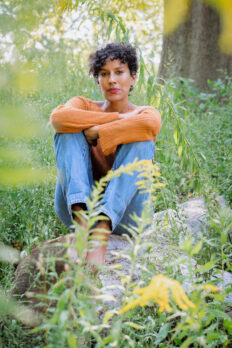

Eaton DC Hotel, Washington DC. April 2023. Over two months, from photos sent to me by friends and friends of friends, I created 32 portraits of mothers of color born between 1881 and 1981. Using charcoal and silver oil-based ink, I transferred their faces to mirror glass. I mounted the portraits on a temporary wall, using wedges of wood to angle them toward the ground. I designed a loop of moving projections that reflected the portraits in negative space in pools of colored light on the floor. I lit candles and incense and filled the room with the smell of sandalwood and honey, the sound of bansuri flute. My mother and two of her friends sat in the front row. My sons sat at the soundboard. The room filled with familiar and new faces. A sister arranged my headset as if placing a crown. I slipped off my slippers and kneeled on a stool on the wooden floor.

In African elephant and certain whale populations, the age and health of the oldest female is an important indicator of the well-being of the youngest animals in the herd. Our healing (or failure to heal) will directly impact the health of generations that follow.

At the end of 2022, my mother fell in her Virginia condo. Days later, hearing her mother was ill, she rushed to Dhaka. It was only after Nani stabilized that my mother realized her own predicament; she’d broken a bone in her back during her fall. I flew to Bangladesh to bring Amma home for treatment, and to help pack up Nani’s small flat to prepare her to move in with my youngest aunt. The mood was one of desperation. My mother, her sisters, and my grandmother, all playing caricatures of their old roles. Competing griefs, casual cruelties, displays of generosity and power. Each one a wounded child and villain by turn. Each of them profoundly undermothered, beseeching one another, beseeching me sometimes, for mothering.

Nani was quiet but lucid. Now bedridden, she did the Daily Star crossword every morning and made little conversation. Aside from her physical therapist, she had few visitors and complained bitterly about being alive. One morning she asked for my book of poetry, which I’d brought her on a previous trip. For hours she sat between the rails of her hospital bed reading it, then called me in.

“I wish I’d met you sooner,” she said.

“You were there when I was born.”

“No, I wish you had been there when I was young. You could have helped me tell my story.”

In 2017, Nani asked me directly to help her heal. I had boarded a plane from Washington Dulles airport after completing a major project, a staged performance of a collaborative poem about trauma directed by actor Jeffrey Wright and performed by US service members who had participated in my writing group at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. That performance would eventually, though I did not know it at the time, become an HBO Documentary. While I’d always faced suspicion as a Muslim woman of color teaching poetry in military hospitals, the new presidential administration changed the climate of my work as patients were increasingly censored and my daily activities were monitored. The stress of the job began to make me physically ill much of the time and I suffered from ocular migraines, which started with blurry vision and ended with searing pain. My mother begged me to come to Dhaka to take a break.

They accuse her of the greatest sin a mother can commit: selfishness. They beg us, their children, to carry their unnamed hurt, as they have carried hers.

The first morning I was alone with Nani, she asked me, “What do you do for the soldiers?”

I explained that the work I did in US military hospitals was mostly about overcoming shame and silence. Dislodging the secrets that threaten to choke us. “I don’t really do much of anything. I just help them find the words through writing prompts, then I listen.”

“Do it with me,” she commanded.

We found a note pad and a pen. I’d read her a poem and give her a prompt on silence or self-forgiveness. The most important part of this work is reminding people that they can write whatever they want and they never have to share more than they want to. They’re not doing it for the teacher, they’re doing it for themselves. “You don’t have to read me any of it,” I told her. “That control remains in your hands.”

Over the course of several mornings, she told me of sexual abuse she experienced at the hands of my biological grandfather, whom she married at sixteen. He forced her to have sex with other men while he watched. Her subsequent divorce was prompted by fear that he would assault their daughters. Ashamed, she held her silence.

Raised in the shadow of their mother’s trauma, my mother and her sisters only knew that their mother’s demand for a divorce created a fog of stigma around them in the punishing conservative social circles of Dhaka in the 1960’s. It made them girls from a broken home.

“He wasn’t that bad,” Amma and her sisters, now in their seventies, have taken to saying to one another in the past decade. “He just had affairs. She just didn’t love him.” They accuse her of the greatest sin a mother can commit: selfishness. They beg us, their children, to carry their unnamed hurt, as they have carried hers.

***

Around the room a tray of mirror bits is passed. Each person takes one and holds it carefully.

Take a deep breath. Hold the mirror fragment in an open palm, and place another palm on your heart. Now inhale deeply. Close your eyes. Make peace with your disbelief. Allow it to sit beside you, humming and fussing. Pat it gently, acknowledge it, and tell it (tell yourself): but what if you don’t know everything?

Return to this moment, to the shard of glass in your palm. Notice its contours, its shine. Now close your eyes. Try to picture the mirror fragment in your palm. If you need to look again, look. Close your eyes again. Pressing your non-mirror palm into your chest, feel your heart beating. Tap your chest gently with your forefinger.

Around the room a tray of mirror bits is passed. Each person takes one and holds it carefully.

***

I asked Nani what she hoped her story could teach. “Don’t fear the society,” she said. “Society is waiting to pounce on you. Stand up to it. Suppose I did tell my story at that right time? Would I catch help?”

Or would she have caught hell?

And now? Would my mother and her sisters be able to accept this truth? Would they be able to believe her?

Just before leaving for Dhaka, I was selected as the 2023 Pauli Murray Art for Racial Justice Fellow by the Antiracism Research and Policy Center. I was to present a public performance and exhibition by the end of April. In Dhaka my project became clear. I was studying and dreaming to design a ritual to take responsibility for my own spiritual health, to understand my mother’s and grandmother’s limitations as products of a society that refuses women’s pain, and a global environment that sees people of color and their children as an expendable, replaceable, interchangeable, less-than-human commodity. To release myself from dependency on the myth of the all-powerful mother as the source of my grief and shortcomings. To unbind my mother and myself and my grandmother from shame over the cruelties we experienced and the ones we enacted on one another. To release my sons from the task of mothering me.

***

Travel to the places in your body where you feel hurt, or abandoned, or disappointed by her.

Imagine that pain traveling first to your heart, then, eased on by the tapping of your finger, through every cell of your body (if it gets stuck somewhere, gently move it along with a deep exhale). Let the grief glow and pulse as it travels through an arm, up to your open palm, into the mirror fragment. Allow the mirror to absorb it. Open your eyes briefly to see it there, crackling in your palm. Now summon the feeling of love or longing you have for your mother, for her face, or scent, or perhaps for the unrealized idea of being held, being accepted, of belonging, of protection. Allow that to travel through your body as well. When it travels up your arm, it hits the mirror and turns to light, reflects forward whatever beautiful thing allowed her to survive, and lets the silt of her grief sink.

Let us say together: may the pain be absorbed, may the light multiply.

***

I’ve kneeled on a jainamaz and said my prayers, freshly washed in threes. I’ve yearned and reached, I’ve pretended. I’ve tapped my forefinger against my knee to stab shaytan, I’ve swiveled my head left and right to greet the angels perched on my shoulders, Assalam wa alaikum warahamatullahi wabarakatahu. I have strained to hear a response.

Humans and other primates descended from small mammals who burrowed underground. In the dangerous time of large reptiles, these early mammals survived by planning and innovating, what some neuroscientists refer to as the ‘probabilistic oracle’: the ability to relive and play out scenarios in dreams, then use the lessons learned in dream spaces to shape and survive the future. This may be why early humans valued communal dream interpretation. We made things up, then we made them come true.

Despite my weak faith, when I must cross through darkness alone, when I hear an inexplicable sound, when I must do something I feel unprepared to do, I return to the only spells I know.

In Bengali culture, forms of magic and divination have a long and respected history that predates the introduction of Islam. For centuries, shamanic leaders, who were often women, played a role analogous to the one filled by psychotherapists in modern societies, assisting with community grief, loss, and psychic disturbance. Healers of the spirit act as conduits between the tangible and unseen worlds, through magico-religious practices that include astrology, numerology, animism and mysticism. But now in Bangladesh, an Arab way to be Muslim has rendered many such practices taboo.

Despite my weak faith, when I must cross through darkness alone, when I hear an inexplicable sound, when I must do something I feel unprepared to do, I return to the only spells I know. I know they’re not quite mine, not quite right. I refuse to beg for mercy from a god who rejects my worship when I’m menstruating. I refuse to stop believing in magic. I need new spells.

English (my only language of true fluency) arrived to most of us through terrific violence and epistemicide: the elimination of ways of thinking and knowing. Before language comes sound, inherent universal meaning. The sound ma, for example, occurs in the word for mother in many human languages. There are things known more deeply than socialization, or so-called civilization. One theory on the origin of language: early humans, having lost the hair other primate babies use to hold on to their mothers, had to lay their young down while they worked, and so began making sounds to soothe their children from a distance. The beginning of language: love crossing space. Language is taught. Sound is known.

All over the world, variations of the word shaman refer to a person who, through dedication and study, has access to the unknown/unseen/spiritual world. The German schamane, from Russian sha’man, from Tungus saman, Chinese sha men, from Prakrit samaya, from Sanskrit sramanas. Schamane sha’ man saman sha men samaya sramanas. I don’t imagine this project as a return to a time long past—colonization has happened, the printing press has happened, the Internet has happened. I am calling for a revival of old practices to access new knowledge, to place ourselves within a lineage of human thought.

It is not always a literal death, but the end of the assumption of protection, of the dependent self, of expectation. The mother makes a mistake, falters, fails, cracks, chooses herself over us, experiences a pain she cannot fully hide.

In the Russian folktale “Vasalisa,” a dying mother gives her daughter a doll and instructions. Vasalisa is to hide the doll, keep it close, and when the time comes, to trust it. The doll is her intuition. In order to access this intuition, Vasalisa’s good saintly mother must die. Vasalisa must experience the pain of abandonment. She must enter the darkness on a quest of her own. Only then does the doll awaken and guide her to safety with little nudges: yes, no, this way, that way. The death of the mother, according to scholar and psychoanalyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés is the beginning of our power, of our self-determination. It is not always a literal death, but the end of the assumption of protection, of the dependent self, of expectation. The mother makes a mistake, falters, fails, cracks, chooses herself over us, experiences a pain she cannot fully hide. We are exposed. It is horrible, terrible, frightening, undeserved. It is necessary. If arrived at with intention, it is an opportunity.

Sit with whatever has come up for you, do not run now. Allow the feelings to lift you like a wave, to place you down gently just a few feet over.

An altar is being passed. When it arrives to you, please gently press your mirror fragment into the mortar, in a spiral, placing pieces on the outermost edges, then starting a second concentric row, so there’s space for all our pieces.

As you press your piece in say: May the grief be absorbed, may the light multiply.

The week after the ritual I set an alarm for 2 am so I could speak with my grandmother. My cousin in Dhaka connected me to her via video call. We tried to show her the performance recording, but the audio was poor. Instead I sent her the text and she read it on the phone, her thick lenses and big eyes moving on my screen as though I was standing behind the words.

When she finished, I asked her how she felt. “I don’t feel any shame, I feel catharsis. I feel such a relief. I can’t believe you had the courage to do this.”

“We had the courage to do this,” I corrected.

Nani, finally free from contemporaries and elders whose judgment she feared and approval she sought. I, able to build a community that accepts me and ready to refuse the ones who don’t. Perhaps the death of the too good mother is not about the child. It is the death of an idea that lives inside ourselves. It empowers us to claim our place as the central figure in our own stories. I hope that my sons believe my story, but even if they don’t, I hope they are able to take responsibility for their own healing.

We take three deep breaths together.

When the rains are strong enough

the water floods the delta,

a river can reverse its course, can flow upstream.

Let us become an abundant rain,

let us allow the silt of their grief to sink.