**

**

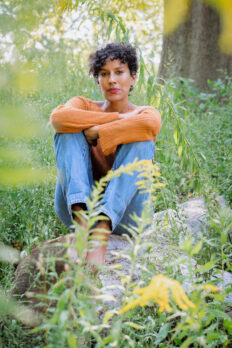

So We Can Know: Writers of Color on Pregnancy, Loss, Abortion, and Birth (Haymarket Books, 2023) was published eight months after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, ending abortion as a constitutional right in the United States. Yet this gathering of confidences, questions, griefs, arguments, meditations, angers, wishes curated by Neustadt International Prize-nominated poet aracelis girmay emerges from and arrives with the weight of centuries. Of what could not be said or thought for and across generations; of what demands analysis despite remaining veiled and secret; of wounds inflicted by, and devotions forged despite, rules and shames that have tried to separate so many human lives from love for the sake of rule and profit.

This anthology is an offering; a cornucopia of hard-earned wisdoms and fraught, vulnerable longings. Or, as I have received it, of wisdoms that protect my longings for the elsewheres that are our children, in which our children thrive. By our children I mean not only children we are raising, or children we have lost, or children we are waiting for, but also, the children we have been. girmay’s editorial eye is curious, tender, and unflinching as it traverses complex historical and cultural terrains that are often cut out of mainstream discourses around reproductive rights. It orients away from reductive, one-stop solutions and toward the forces, agendas, and silences that contextualize each experience of desire, loss, pregnancy, birth. In this way, So We Can Know enacts the kind of political, sensual, and emotive attention constitutive of care that girls, women, mothers, and birthing people of color rarely experience.

Cynthia Dewi Oka (CDO): In the preface to So We Can Know, you write, movingly and precisely, “I inherited the hushed voices of my mothers as did many of my friends. Somewhere along the way though, I began to need these stories. I wanted to listen to all the ways that women and girls had tried to live. Which choices seemed big, which choices seemed tiny, and which seemed not choices at all.” Having gathered some of these voices in the space of the anthology, can you talk about what you learned about the hushings that so many of us grew up with, and how they informed or were informed by the complexities of “choice” as women (which is also to say, girls and daughters) of color? What did those hushings cost us, and how (if at all) did they protect us?

Aracelis Girmay (AG): It is exquisite to witness here the utter diversity of psyches and expressivities written into the pages of this anthology (because of the writers’ perspectives but also because of the lives that made their lives). It feels important to say that so much of this work reflects how many of us were raised by people who interpreted their environments with calculation, brilliance, resourcefulness, trauma, and grief, oftentimes in impossible situations.

My interpretation of the silences I was raised with had to do with who my models were but also my own inner life and psychology. In my case, some of the silences that my people attended made me feel like there was not space for my questions or that those questions – about sex, pleasure, contraception, pregnancy – should not exist for me at all. This gave me the strange and simultaneous sense that I was unequipped to know but that I would also “master” all knowing when the time came. I am certain this had something to do with how late I was to practicing the language I needed. I was so curious and cautious and fearful, and did not have people to talk through these nuanced questions with. As you note, this reality is part of what informed my commitment to this anthology.

In her essay “we participate in the creation of the world by decreating ourselves,” Jennifer S. Cheng thinks about infertility treatments, loss, grief, the birth of her child, and the decreation of herselves. For instance, she writes: “My first public words about your birth wereIt is such a wilderness. Followed by, I am trying to process how the world has shifted. If I had been more honest, I would have used the word undone.”

It takes such work to reflect, to scrutinize, to change or complicate the ways we look at our lives. (I think of Audre Lorde’s “The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives…” whenever I think of this word, this action “scrutinize.”) I have been wondering what conditions make this scrutiny and honesty more or less possible for any given person. Rigor, capaciousness, imagination. Perhaps an ongoing relationship to the effortful attempt to articulate something as Cheng writes further:

“I was seeking new texts on the fragment, on silence, and suddenly I thought, Is this what life consists of? Sites of silence, one after another, that we move through, attempting to speak.”

“Which is to say, infertility: like being under a dark continent. And since there are no words in our social spheres for this kind of liminal grief, you say nothing about the invisible continent enveloping you at all times.”

Alongside this thought, I am thinking of Mendi L. Obadike’s words at our first anthology event back in February. She spoke about her changing relationship to writing across four miscarriages before the births of her two children, noting that for her, choosing not to write is also a decision that is important and valuable to think about. Her words: “Remembering the refusal to put language on some things as well as the embrace of language for some things.”

Quiet can help you to live. Loud can help you to live. But it feels very important to at least try to know what they are made up of at any given time.

I’m also thinking of Vanessa Mártir’s essay “1994.” She writes about the experiences of being a pregnant young person in an abusive relationship, shamed by nurses, and the actions she took not to have a child. “I did what I had to do. I was not ready nor was I equipped to be a mother.” She writes this essay almost three decades after the events around which they turn. She writes about the hard work of coming to love and care for all your selves, across time, and to fiercely interrupt the hushes of the ones who silenced and shamed her. She makes a space, many years later, for these selves to sound.

So in the span of just these few examples, there are perhaps the “hushings” of disorientation, isolation, lack, ostracization, shame, inarticulability, listening, protecting an experience from language or an impulse to narrativize. Quiet can help you to live. Loud can help you to live. But it feels very important to at least try to know what they are made up of at any given time. I’ve seen people raise their voices and fists when mistreated, and others seem to vanish into thin air. Or to go underground. I understand that sometimes these are strategies that people stay with all their lives. Others have tendencies and sometimes change them. There are the hushings of the hushings of others. The hushing you do when you do not want to interrupt a wilderness you’ve stepped into.

CDO: How has your understanding of the relationship between mothering, art, and political practice evolved? I am curious about the beliefs that you began with as a young person (or a young poet) and where your investigations as well as lived experience has taken you to at this point in your life. Mainstream feminism typically constructs these clusters of experience as separate and/or even hostile to each other, a view that has impacted (and limited) how policy is imagined in the US for birthing people, but the voices in this anthology seem to point to a reality where they are embedded in each other.

AG: I know that the state is built and preys on the economic, laboring, and cultural lives of Black and brown people in this country. I have known for a long time. In Jackie Wang’s Carceral Capitalism, she quotes a 2016 brief from the U.S. Department of Education which notes: “Over the past three decades, state and local government expenditures on prisons and jails have increased about three times as fast as spending on elementary and secondary education. At the postsecondary level, the contrast is even starker: from 1989-90 to 2012-13, state and local spending on corrections rose by 89 percent while state and local appropriations for higher education remained flat.”

The hostilities of the state – extractive, predatory, and racialized, all by-design: protect the devastating status quo of racial and economic disparities; secure a white, patriarchal ruling class; criminalize poverty; normalize the poisoning of our world; normalize policing; enforce and normalize the generational exploitation of Black and brown people by corporations, institutions, municipalities, school systems, and police forces.

What was clear to me as a young person is now differently clear. As a parent, I am witnessing for a second time what I do not remember as a child. I am around children all the time because of my own children. I am involved in caring for young people, and therefore attending to their bodies, lives, psychologies, dreams, and questions. I am witness to other children and their families and what this means is I am witnessing how these projects are inflicted upon all of our children and how these projects necessitate, in fact, depend on, the squandering of the genius, rights, and lives of some of the ones of these children who are poor, unhoused, Black, brown, trans, female, learning English, immigrants, and/or all of the above.

The elsewheres that people talk about, that we are working to imagine and make, these children all come with those visions. That is some of what a child is and what a child needs.

In other words, I am experiencing how deep, how ubiquitous the state’s dual project is of indoctrinating and subjugating (crossing my arms to James Baldwin) us into its violent structures. But what is also true is that I am witnessing the powerful work of caring for children. And the powerful things children wonder and know and say, their wisdoms and challenges, and the ways so many of these caretakers are alongside them trying to attend to their lives with brilliance, fight, analysis, flexibility, and communities of care and collaboration. To hear a child making up a song in the other, empty room – or to watch a child bending his body toward the garden, or to hear a child talk about the absurdity of slavery. It is profound. I think of our neighbor walking home with his grandmother, reaching out for her arm every now and then, to lean on it a second, and then let it go. It is a sincere and powerful togetherness.

I am hearing all the time Audre Lorde’s “we were never meant to survive…” This is not a world made for our survival or for the moral survival of its ruling classes because it is an immorally, predatorily designed world. The elsewheres that people talk about, that we are working to imagine and make, these children all come with those visions. That is some of what a child is and what a child needs. So just as I am now differently involved in and tethered to the state, I am more generally in new and different relation to so much. And so my commitments and conflicts and failures and rejections are all shaped by this new relation of caregiving. I see what is at stake. I witness the slow and quick squandering of our children. I am complicit in it as I work to reject it. I reject it.

CDO: I am also interested to hear your thoughts on mothering and its physicality. I don’t mean solely the biology of reproduction or birthing, but mothering as the daily work of caring and providing for, raising, and protecting our children (for many of us, with very little or no societal support). In the preface, you speak about your mother “hiding” parts of her body from you when you were little. How has mothering revised how you inhabit your body in the world? I mean body in the widest sense of the word – as an individual, but also a social, political, spiritual being?

AG: I feel very grateful to you for this articulation about this daily work. My partner, Rassan, does so much of the cooking and cleaning, and still I feel like I’ve lived the past eight years on my knees, under the table, cleaning up crumbs and with a rag to the floor. The work is ongoing, daily, and especially when they were very little and then during lockdown, I had to learn to do the things that I wanted (reading, taking notes, talking on the phone) on the edges of the day.

My experience as someone living in the U.S. feels sharply different since I’ve begun caring for my children. When they were very little, my dad was across the country and sick, and I could feel how impossible our set-up was. How I felt then that his care in California and my caring for our children and working in New York were in conflict. I was devastated by this for a few years and will perhaps always live with this sense that I did not fulfill both things in the way that I should have and deeply wanted to. It used to be that I was a single stone – sitting still, going this way or that way. If I wanted to relocate for a year to help attend to a loved one, I could have made that geographical change for myself and taken whatever economic risk it entailed because I thought I only had myself to feed. I feel differently bound to the lives of others now. And so it has been very interesting to be the mother of these children and a sister and a daughter and a friend and a teacher and to feel these different relationships change with and because of each other.

There was some language I was working on for a very long time, just after my second child was born. It goes: “I am alive when both my children are born / We draw a circle around us, this is what we can pay / What will that get us, how much time?” I have felt curious about my impulses, disturbed by how small that circle gets sometimes, how insular. I didn’t know how petty I could be, and nitpicky—especially when in deep, deep collaboration with a partner and trying to divide the load and time. I have also felt excited to witness other changes in myself—a relationship to reflection and failure and the ongoingness of trying to show up openheartedly that feels differently vulnerable.

I am thinking of Simone White’s poem in the anthology “Motherhood Is a State of Hypervigilance” and her words: “danger, failure to possess / holding what cannot be held”. Everyday. Work. Vulnerability. Surrender. Vigilance. Sweetness. Trust.

CDO: Given the contested terrain that is “family” and its particular constructions and uses under conditions of colonialism, white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy, I am wondering how you are thinking about the project or process of family-making? Has working on this project changed how you think or feel about what family means or could be?

AG: What I continue to learn from the work in the anthology has to do with how folks care for each other and/or wish they had been cared for.

There are so many explicit instructions here, but also quiet ones if we are listening. I’m thinking about how I invited Emily Raboteau and Angie Cruz separately to submit work for the anthology. Angie and Emily are friends, and somewhere along the way Emily wrote a writing prompt for Angie (published in So We Can Know as “Questions for Mama’s of Sons”) and Angie responded with the essay “When My Son Came to Me.” I was moved by this example of collaboration and friendship, and how they worked together to help dislodge or awaken the writings that they felt compelled to share. I’m thinking about Cheryl Boyce-Taylor’s “Born Ibeji” in which she writes: “I tried to hide my pregnancy from my mother, but I was seventeen and she knew everything about my life. She knew I was pregnant before I even told her. This news broke my mother’s heart, and even though she was super religious, she decided that I would have an abortion.”

I am thinking of Marta Lucía Vargas’ “Radical Intimacies.” It is an offering of powers, imaginative strategies, gorgeousness, and practicality: “I run a local vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) group with a friend. We create safe spaces. We share birth stories. We read books and organize author events. We help each other make choices for desired birth experiences. We encourage getting needs met, even if it means switching providers in the eighth month.” And then later: “My nature is to push against the limitations of mythic violence and push for mystery. I want to keep in step with wild dreaming, protect her from being silenced, forgotten, annihilated. I am at her mercy.”

A few things that this editing experience have deepened in me: at any given moment, each of us is carrying so many things, and there’s life – school, care taking, working jobs, the deaths of loved ones, illness, cooking a meal, sitting in front of a window as it rains. Everyone is tending to their lives and the lives of their beloved people and communities, and so for a project like this to exist it takes many moments of carving out space, juggling, presence of mind, and work.

I am learning from you all’s writings but also from all that correspondence as we worked on the anthology. I learned so much from the texts and emails. The openness in those communications which had to do with you all (and Maya Marshall, Haymarket editor) setting expectations; sending notes of love and care; saying yes or saying no to something; expressing your needs; sharing your experiences of writing these texts, old memories emerging, new or old language that felt especially intense as we – distant but together – worked through the uprisings, lockdown and the beginning of the pandemic. I do not personally know quite a few of the writers in this anthology, but I feel in deep relationship to you all’s work and practice because of those exchanges. I learned something about patience, grace, and trust.

CDO: What would fulfillment as a person who mothers, and has been mothered, look like for you?

AG: To learn some of our old words alongside my children. To pay attention to what energies and experiences nourish my children and partner and those we’re in community with, and to do something together in a kind of meaningful, ongoing, maybe shifting way…

On the one hand I want to be in the shadow of mountains just carrying stones in my arms, close to my heart. Quiet enough to hear what is not human and not myself. And on the other hand I want to follow the example of Toni Cade Bambara who, as Nikky Finney tells it, was many years ago stopped on the street by a man who heard she was a writer. He needed help filling out his housing papers and she said something like, Okay, come by my house around 4… We’ll figure it out. We’ll figure it out. To be shoulder to shoulder in meaningful work. These are kind of emblematic visions for the ways I imagine the subterranean energies of a fullness of life.