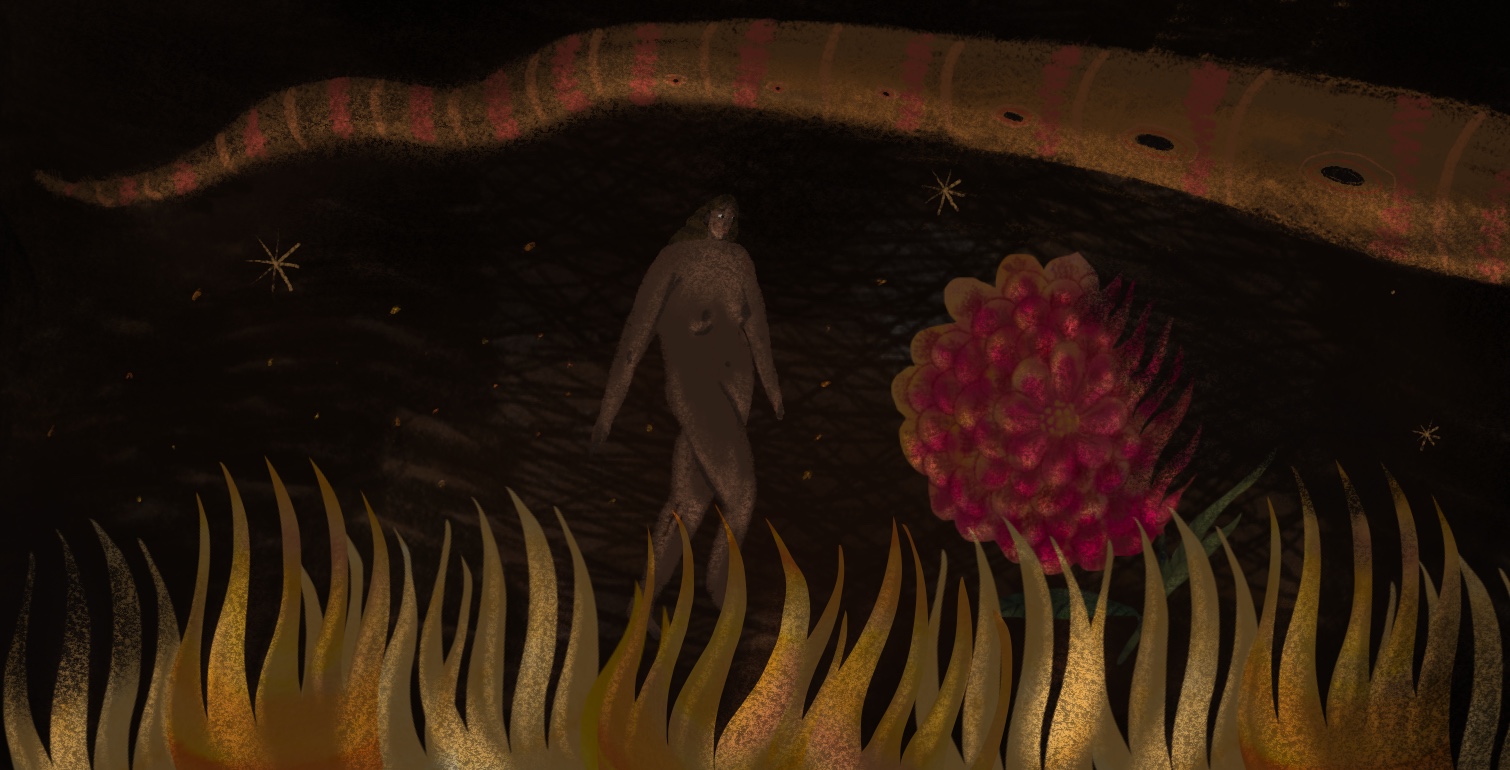

From Túxpam de Rodríguez Cano, on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, to Tula de Allende, more than 300 kilometers inland, flows an underground river of toxic amber. The infrastructure that carries it is a monster with hundreds of necks that run parallel to the main roads on the east side of the country. Near its final destination, on the stretch that runs between Teltipán de Juárez and Tlahuelilpan, the steel body of one of the pipes breaks through the eroded earth. At first, no one notices; no one cares. It takes a few wet summers and scorching Mays to rub it thin but then, in an instant, its back splits open like a wound. A sudden squirt of fluid sprouts from it, a squirt which becomes a torrent at the first blow of a pickaxe wielded by a man who was attracted by the smell of liquid fire and the promise of wealth. The dry land is easily soaked.

It had been a particularly warm winter. The early morning mist rose over sheet roofs that dripped with glittery dew, and the sun peeked over the horizon, heating the corrugated metal. In the distance, a rooster crowed. Jimena, who heard it every day as a sign that her boys were already late for school, had never wondered about its exact origin, but that morning, while she cleaned a stain of sauce from Sebastián’s shirt, she thought “Maybe from the other side of the field.”

A moment later she threw the door open and hurried the children out of the tiny brick house. Jimena, the Widow Cano, was a short woman with a broad torso and strong legs, which were particularly useful when she had to run errands for the Flores or carry Ernesto in the mornings. Sometimes the boy refused to walk to school and he had to be taken by force, between jerks and spankings. This morning, however, Ernesto was striding happily behind his brother, and for that Jimena was grateful.

It takes a few wet summers and scorching Mays to rub it thin but then, in an instant, its back splits open like a wound.

They walked, as they did nearly every day, the almost three kilometers that separated them from the town center. Most of this stretch was covered by an open field and the shortest way to Tlahuelilpan was to walk along the highway that intersected it. Sebastián led from a distance, fumbling with his half-opened backpack and pretending not to know his mother and younger brother. Ernesto tried hard to keep up; at six years old, he was as tall as a child of four. Evidently, neither her genes nor his diet had helped much with his growth. Jimena knew that, like his brother, Ernesto would one day hate her for that shortfall, but both deficiencies were equally out of her control.

A little behind, but constantly yelling at her children to watch out for passing cars, was the Widow Cano. Her late husband had not yet been underground for two years, but it seemed to the neighbors that Jimena had been born with that name. They called her the Widow Cano, partly to differentiate her from the other Doña Ximena, the one with the little store, and partly because there was nothing else to make her stand out, nothing but the fact that in 2017 a stray bullet landed in the temple of Víctor Cano and left her without a husband, without a solid livelihood, and with two boys to raise. No one knew who fired the gun and no one was ever prosecuted. Drunken men quarreling or a failed attempt to hit a drug lord; it made no difference. Jimena had no hope of justice, and even justice could not bring her husband back.

No one could understand how she managed to support Sebastián and Ernesto without taking them out of school and putting them to work full time. Among the neighbors, there was much talk about the type of products and, above all, services that the Widow Cano would have to offer in order to get enough money to raise her children and not starve herself in the attempt. The truth was that Jimena Cano was a very intelligent woman. During the twelve years of her marriage, Jimena hid a small box under the bed where she secreted away all the money that Victor left around the house, forgotten. It consisted mainly of the coins that fell from his pockets when he came home staggering drunk and Jimena had to undress him as part of her wifely duties. The next morning, if Victor had enough mind to notice he was short of money, he always attributed the loss to his drunken night out and imagined that the money had been well spent. And so, by buying seven pesos of tortilla instead of a kilo, and walking every Sunday to Mass in Tlahuelilpan instead of taking the combi bus, Jimena Cano had managed to raise enough money to support her children—although mostly on bread and milk—for more than a year and a half with only her salary as a maid.

During the twelve years of her marriage, Jimena hid a small box under the bed where she secreted away all the money that Victor left around the house, forgotten.

What was that money originally for? Even she was not sure: for Ernesto to go to university, or to help Sebastián if he ever got into serious trouble, or to pay for doctors and hospitals if anything ever happened to Víctor (anything less fatal than a bullet to the head). Or, to be used in case one day she finally, miraculously, made up her mind to leave her husband.

Sebastián was ashamed of his mother and could not stand his brother. He hated school, he hated his skeletal body, and he hated his age. He liked to say he was fourteen years old, even though he was actually twelve and seemed to be ten. Either way, his high school friends did not care as long as he could keep up with them and help distract Doña Ximena while they stole a pack of cigarettes that they would later share in the vacant lot behind the school. Sebastián’s school (or as he called it: Ernesto’s school), Felipe Carrillo Puerto Elementary, was only a block away from the only high school in the area. Close enough for Sebastián to run back there at five in the afternoon, when his mother came to pick him up from, she believed, soccer practice.

Ernesto’s school was already looming around the corner. It was a square, ugly building, with dirty white walls painted with campaign ads for last year’s election. Every time Sebastián saw them he thought the same thing: when he grew up he wanted to be governor, perhaps one day of the State of Hidalgo, perhaps one day president. He went through the school doors without saying goodbye to his mother, followed by Ernesto, who did stop to receive his blessing.

The fantasy made rounds in his head as he walked into the overcrowded classroom, knowing he would bolt after the first class. Money and respect. All the money he wanted, as much respect as he could buy. No one would ever make fun of: his slim legs, his brother who “looked like a retard,” his mother who “let herself be fucked by a thousand men every night and charged so little that she could not even toss her sons a piece of pork from time to time and so must do for pure pleasure,” of his father who killed by a stray bullet so surprisingly accurate that it came out clean without breaking his skull into a thousand pieces. What things would he not do with all that money? Sebastián thought, smiling.

Ernesto, despite his young age, understood everything. He understood that his brother was bad because he hit him when they were alone and that his mother was good because she gave him mints that she took from the Flores’ house. He understood that his father was never going to come back, even though nobody ever explained why.

The fantasy made rounds in his head as he walked into the overcrowded classroom, knowing he would bolt after the first class. Money and respect.

Ernesto, unlike his brother, enjoyed going to school. If he cried and complained in the morning, it was not because, as his mother believed, he did not want to go, but because his legs often hurt from so much walking. He did not mind waiting until five o’clock every day after classes for his mom to pick them up. Ernesto understood that his mother had to work at the Flores’ house until just before that time and that was why he had to spend so much time drawing and coloring in the school yard as he watched the older children play soccer. He understood that Sebastián should have been playing with them, but he was smart enough not to say anything because he did not want his brother to hit him again with Dad’s belt, the way Dad used to do.

Ernesto also understood that they were not allowed to walk home alone (although that would have allowed him to move at the pace he wanted so that his legs would not hurt too much) even on days when there was no soccer practice because, although the way was straightforward and easy, his mother was afraid of letting them walk along the big road between the house and the entrance to Tlahuelilpan. It was so silly. Ernesto was not a little boy anymore, and he knew he had to be careful of the passing cars. They were always so loud on the road that he could have felt them coming even with his eyes closed.

It was four thirty in the afternoon and Jimena, bent over the ironing board, felt her sweat-soaked shirt sticking to the skin of her back. Her legs were itching inside her jeans. Twenty more minutes. That would be about four more shirts to iron and then she could pick up the kids and they would go straight home. Jimena tried, as always, not to think about the walk back home: another hour under the sun before she could finally get some rest. She had been working since eight in the morning at the Flores’ house. She had swept, mopped, cleaned the bathrooms, cooked, washed the dishes, washed the patio, washed the clothes —only handwashing would do for the cashmere sweaters and la Señora Flores’s American bras. She hadn’t stopped for a moment because, since Victor’s death, every time she caught her breath between chores, the fear of losing her job—and the thought of what would happen if she did—would come rushing in. To avoid thinking too much about it and to distract herself, she would wash something else.

Jimena was about to start ironing the penultimate shirt of the day when she heard her name being called from downstairs. She unplugged the iron and went to meet la Señora Flores, who was waiting for her in the vestibule, a room that was as large as Jimena’s house.

“Doña Jime, you live on the way to Teltipán, don’t you?”

“Yes, Señora.”

“I was just told that there is a broken Pemex pipe around there, I imagine not far from your house. Felix just texted me to let me know they just received the report but, of course, there´s been people with bottles and buckets there for almost an hour. It will be all over the news soon. You know how people are… You’d better get out of here, Doña Jime, before the road gets closed or the military arrives.”

…every time she caught her breath between chores, the fear of losing her job—and the thought of what would happen if she did—would come rushing in.

La Señora Flores smiled a little at that, as if she found the idea amusing. She was vicariously living a more exciting life, full of risks and full of struggle. She was proud of herself and her good deed of the day.

“Yes, Señora. Thank you”

“Go on, Doña Jime. Take care.”

Still, it wasn’t until after five in the afternoon when Jimena left the Flores’ house. In her anxiety, she forgot to take a couple of mints from the bowl on the coffee table for Ernesto. She didn’t exactly know what was causing her such uneasiness. It was not quite fear or even real worry, it was a rush to get home and hold her children safely by the hands before deciding what to do next. It was the excitement caused by the fortune of having a liquid gold mine sprouting next to her house, of knowing that luck like that would not last long or repeat itself. She thought that she would have to carry Ernesto most of the way to get to the site of the spout as quickly as possible, and she tried to remember where in the house she had put the blue bucket, the largest one they had at home. She also hoped this time Sebastián would already be at the school entrance, so that she did not have to wait for him, as she often had to wait when soccer practice went on for longer than normal.

Sebastián ran as fast as he could and yet, he could not catch up to the others.

This could not have happened on a worse day. The most exciting event in all of his life had to occur on the hottest day any of them could remember. The sun was beginning to move towards the west but to Sebastián, its rays still hit harder than ever. He was out of breath but he kept running even when he could no longer feel his legs.

Twenty minutes earlier, while Sebastián and his friends were sitting in the vacant lot among cat droppings, empty beer cans, and the ashes of their cigarettes, Diego had received a text message from one of his older friends, one of those who had already left school and that Sebastián so much admired. In the text, the friend explained that a gasoline pipeline had ruptured on the highway between Tlahuelilpan and Teltipán, and it looked like a fountain. They were giving away the fuel and everyone was there, everyone except them.

It was the excitement caused by the fortune of having a liquid gold mine sprouting next to her house, of knowing that luck like that would not last long or repeat itself.

Before he knew it, Sebastián was already running after his friends, trying to concoct an excuse that would keep him out of trouble. He would tell his mother that he tried calling her from the phone of one of his teammates but that there must have been no signal because he tried for such a long time and could not reach her. He would tell her that the father of one of his friends who had a truck wanted to go to the site of the leak and offered to drop him off at his house because he knew they lived nearby and, fearing the road would be closed at any moment, he did not have time to decline. He did not think about what excuse he would give for leaving Ernesto alone. As he ran he could not think of much more than his feet hitting the pavement of the road next to the field, very slowly, too slowly, of his skinny legs that could not move fast enough, that did not move like the others’ did.

He was desperately trying to catch up to his friends, to not lose sight of them. If he had hesitated to follow, they would have called him a fag. If he stopped on the way to rest, he would go back to being a child or become a woman in the eyes of his friends. If he got there too late he would miss out on all that money, liquid money, all free, gushing out as a fountain, he had been told.

Jimena was crying. She was crying and sweating and running with her youngest son hanging from her back, clinging to her neck.

She did not know with certainty where Sebastián was but she could guess, by some hunch, that he was at the site, or hopefully in the house, but that he had left Tlahuelilpan. In any case, she did not know where else to look and, if her son was in fact near the leak, she did not have much time to lose.

She was not the only one running. Next to her, the other women and children hurried along that stretch of road with empty jerry cans and jugs because the rumor had spread like wildfire. Even elderly people who were barely able to walk and could carry no more than a couple of water bottles were making their way on the road. Everyone was screaming and laughing gleefully because the soldiers who had just arrived were giving away gasoline, and gasoline was expensive, and there was little of it. On the news a couple of weeks ago, the presenter said: “If you can fill up your car’s tank, do it, because from this presidential term on, gasoline will be liquid gold.”

The sky was darker by the second.

Jimena stopped suddenly and lowered Ernesto from her back.

“My love, I have to run to see if your brother is in the house. You know which way it is?”

Ernesto nodded.

“Right, all right. I’m going to be waiting for you by the side of the road near home, but I have to see that your brother is okay first. Do you think you can get there alone?”

Ernesto nodded once more, though with a little less conviction.

Everyone was screaming and laughing gleefully because the soldiers who had just arrived were giving away gasoline, and gasoline was expensive, and there was little of it.

“I know that you can, mijo. You are my boy, the most handsome and the smartest and you always help mom a lot. I’ll run, mi niño. I will see you further ahead, by the road. Wait for me by the road when you are almost at the end of the field.”

Jimena leaned down to kiss Ernesto’s forehead and, without saying more, bolted towards the mob of neighbors that she could already see gathering ahead.

The smell was overwhelming. A little away from the crowd, Sebastián saw a woman being sick from the fumes of the fuel. His own eyes were tearing up and his nostrils burned.

They had gotten there on time. And it was true: the jet of gasoline shot into the sky, ten feet high. Juan and Diego had gotten a couple of jugs, who knows from where, and they were making their way through the crowd toward the river of oil that had formed around the fountain.

Sebastián was still sweating. He was thankful for the gasoline that splashed on his face and cooled him down. Everything around him was euphoric as people shouted and laughed; they poured the liquid on their faces, on their hair, on each other. The soldiers were observing them from a distance, apart from the chaos. There were too few against the mob of civilians, but it still seemed strange to Sebastián that the soldiers were not trying to stop them, that they were just looking at them with that expression of superiority that police and government officials always wore. Maybe when he grew up he would like to be in the military before he was governor, Sebastián thought.

It was seven at night and the sun had already set, but the heat was still unbearable. The liquid smelled like fire but felt cool to the touch. Sebastián stuck one foot into the golden river and then the other, then his bony knees and a meager thigh after the other. He walked toward the spout until he no longer could see where it ended without looking up and getting oil into his eyes. He soaked his hair, his clothes, his skin.

Behind the jet, among the crowd, Sebastián thought he saw his mother approaching in the near darkness. The Widow Cano had found him and was looking at him now with the same expression she’d had on her face when a voice inside the phone told her that her husband was dead. Beside her, a man with a cigar butt dangling from his mouth leaned over to fill his fourth jug.

The liquid smelled like fire but felt cool to the touch.

Ernesto reached the end of the field by the road, where trucks parked in a triple line waited to be loaded with drums of fuel. His mother was not there as she had promised, but he knew she would not take long. Ernesto waited in silence, straining his neck to see what was causing so much fuss in the distance, deep into the pasture.

It was, first, a whip of fire. An orange snake lit up ahead, on the other side of the field. Then he heard the explosion and a column of flames rose high, taller than any building Ernesto had ever seen. A wave of heat hit him in the face and ruffled his hair. It rolled past him, leaving empty air. People began screaming. The cars were honking non-stop, their drivers frantic to get out of there. There were people crying but although he could hear them, Ernesto did not see them. All he saw were the figures running away from the blast site, glowing figures that looked human but did not move like humans.

They screamed. They ran towards Ernesto, towards the highway, asking for help. People ablaze fell to the ground before they could get too close, that rolled on the ground, igniting the tall grass on which they squirmed. They smelled like pork, sulfur, crackling nails, an autoshop. Dark, shapeless figures, their skin splitting open and falling to the ground in tatters. Red figures, without hair, without lips, with open eyes and no eyelids.

Ernesto did not understand anything.

Author’s Note

“The Pipeline” was inspired and very loosely based on events that took place on January 18th, 2019 in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. At least 137 people lost their lives and many more were injured when a pipeline transporting gasoline exploded in the rural town of Tlahuelilpan. This story was originally written in Spanish and later translated and adapted for an English-speaking audience. In the process, I realized that the latter would react with surprise and even incredulity at the casual violence and cruelty that I, along with many other Mexicans, have so sadly normalized: There are places in Mexico where stray bullets often kill innocent people and no one is ever prosecutes; the army idly watching civilians die is not something that would raise many questions. I write this hoping that, one day, a story like this will not pass for anything but the wildest of fictions.