Black Lesbian Feminist Socialist Warrior Poet Mother Audre Lorde was always looking for her dead. In phone booths, in shop windows, in weather reports, in other people’s names, in other people’s books. And she exhumed them, her long and recent dead, in her own writing.

Audre’s search for signs started early. In elementary school, her seatmate Alvin died suddenly of tuberculosis. Alvin was the person she describes as her “first ally” in their Catholic school classroom. He was better at numbers and she was better at reading. So when the teacher made them read from their primers aloud, Audre and Alvin, both usually relegated to the back of the room for their ungovernable behavior, helped each other out. Alvin helped Audre find the pages and Audre whispered the words he struggled to sound out. When Alvin never came back from winter break, Audre was lost. Educationally and perhaps, existentially. She wrote about Alvin again and again. In one of her first published poems in Seventeen magazine, “The Welcome Committee,” she writes not about any typical teenage concerns but about a little boy, suspiciously similar to her descriptions of Alvin, who arrives in heaven and completely bewilders the angels with his boyish interests.

Later, in her poem, “Brother Alvin,” Lorde, by then an established poet, promises Alvin that she will look for “a new spelling of your name” in “each new book on magic.” In the same collection, The Black Unicorn, in “Eulogy for Alvin Frost,” she wonders if her seatmate Alvin has returned to her through her CUNY colleague Alvin Frost, a faculty ally who died and did not return to school the next day:

“and you might have been my long lost

second grade seat-mate named Alvin

grown into some other magic

but we never had time enough”

Alvin again appears in Zami, Lorde’s biomythography, where she memorializes and fantasizes about her own life. She not only creates a character named Alvin who shares real-life Alvin’s dismal fate, she also subtitles the whole book with that turn of phrase from “Brother Alvin”— Zami: A New Spelling of My Name.

But the death that most haunts and inspires Lorde’s published body of work is the loss of her high school friend, Genevieve, who died by suicide at the age of 16. A series of poems she eventually titled “Memorial I-IV” and several other poems over the years seek out Genevieve’s spirit. In fact, the first word of the first poem in Lorde’s first book, The First Cities, is “Genevieve.” One of the last poems she ever recited aloud, months before she died as radiation broke her voice, was “If You Come Softly” or “Memorial I.” “I love those early lyrics” she squeaks out to the friends gathered in Berlin, “they are so dear.” Genevieve’s death was deeply traumatic for Lorde, made more so by the fact that Genevieve had told her about her suicide plan. Genevieve had survived one previous attempt, and when she ultimately died, Lorde felt so guilty that for years afterwards she had nightmares on the anniversary of Genevieve’s death.

Lorde never stopped needing spells, which is why she never stopped writing poems.

In 1977, more than 25 years after Genevieve died, Audre went to the first Black Feminist Retreat organized by the Black Lesbian Feminist Socialist Combahee River Collective. She noticed that the name of one the women in the room was an anagram of Genevieve’s name, and wondered whether Genevieve and other Black girls and women who had died by suicide might have survived had there been Black feminist retreats in their time.

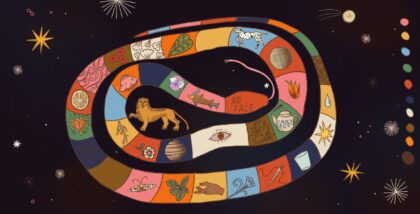

Lorde never stopped needing spells, which is why she never stopped writing poems. She brought Genevieve, just like Alvin, with her into the future. Her act of non-stop looking and perpetual accountability is the inspiration for this oracle. Lorde teaches us that our loved ones are everywhere if only we are listening. And are we listening? This oracle draws from her “Memorial III from a Phone Booth on Broadway,” which first appears in Lorde’s 1974 collection, New York Head Shop and Museum. In it, the speaker recounts a day turned inside out by the need to hear from her friend. She (or they?) rushes (or rush?) into a phone booth and demands an answer.

I have distilled alphabet concordance poems made of words from the poem to create an oracle for us to use here in our study of omens. How does it work? A few steps.

First—breathe. Take nine breaths and notice the depth, heat, and pace of your own breathing.

Decide who you are going to listen for. Let it be someone who you don’t have access to via modes of digital, sign language, or audio listening for some reason.

Decide what you want to hear from them about. Is there something you really want to know from them that would be helpful in your life right now?

Choose an object in your physical space that you connect to the person you are listening for (it can be anything, something that is their favorite color, something blank because you don’t know their name, something they gave to you … anything).

Choose one word to describe the object. It can be any word.

Now use the first letter of the one word you used to describe the object as your oracle letter. Read down and read the concordance poem that matches the letter. If the letter you chose doesn’t appear in the concordance poem, you get to make your own poem using only words that start with the letter you chose.

What do you notice?

May the Lorde be with you always. And also with me.

Memorial III Concordance Poems

A

a

and

a

a

a

against

answer

answer

answer

answer

answer

answer

answer

B

booth

broadway

booth

but

burrs

blossom

back

C

collapses

call

call

D

day

desperate

E

enough

ear

ever

F

from

for

for

for

G

goddammit

H

has

head

I

inside

into

I

inside

if

into

is

I

J

K

L

long

last

M

memorial

must

my

my

must

me

me

N

not

now

O

on

out

over

P

phone

phone

pressed

please

Q

quick

quick

R

S

some

search

spoken

surely

sound

shall

T

time

turns

the

telephone

that

this

this

the

time

U

up

V

W

whole

works

who

will

will

X

Y

you

year

you

you

you