Illustration: Jia Sung

Illustration: Jia Sung

We were not supposed to know about the man shivering on the floor, curled up like a baby. The incident was meant to remain concealed, along with another incident in the same room, where a man was found on the floor next to a pile of hair, hair that he yanked out of his head in agony from the heat. There were other secrets too, like the children. Boys as young as 13 locked away by government agents, their whereabouts unknown to their parents or anyone other than their jailers.

The evidence, contained in letters, emails, and reports dated 2003 and 2004, printed on government letterhead and stamped “Secret,” or “Confidential,” described events that occurred in sites around the world in the name of fighting terrorism.

I discovered these declassified documents at a museum in San Antonio, Texas in the spring of 2019 when, just a four-hour drive south, in the Rio Grande valley, men, women, and children were on the ground, shivering, locked inside Border Patrol processing centers they called hieleras—ice boxes.

*

Black type on red.

Memorandum from CIA director George J. Tenet

Date: September 16, 2001

Subject: We’re at War

There can be no bureaucratic impediments to success. All the rules have changed.

*

I read through this collection of files after more than 2,000 children, mostly from Central America, had been taken from their parents. The term “detainee” was now synonymous with people tightly packed into cages in the desert heat of our southern border. The images invoked memories of men in orange jumpsuits kneeling behind the chain-linked cages of Camp X-Ray at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Or, they should have, but didn’t.

Instead, the arrival of tens of thousands of migrants at the southern border has been filtered through the nation’s ongoing conversation about immigration. “There is a philosophical debate,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a policy analyst with the American Immigration Council, “about who deserves to be a refugee.” Humane treatment of asylum seekers has been discussed through the lens of the drama of individual stories and the demands of border security.

On the surface, the distinctions between Guantánamo Bay detention camp—GTMO, or Gitmo—and the border appear significant. On September 11th, 2001, George W. Bush declared the attacks on the US to be an existential threat. “Our way of life, our very freedom came under attack,” he said. Men in Afghanistan were seized in the name of war. Asylum seekers, on the other hand, were willingly delivering themselves into the hands of the US government.

Liberals debate whether the deplorable conditions at detention centers qualify as concentration camps, digging through the annals of European history to decipher the meaning of locking up families. Political rhetoric equating the arrival of thousands of asylum seekers with an “invasion” is described as “conservative.” Demands for military deployments to the border, more detention, and more security are labeled a “hardline” stance on immigration.

Such arguments, however, reflect the gaze of a nation looking outward, at the “other,” and across a border. The objects of the gaze become the central focus while the gaze itself escapes scrutiny. But reading these declassified documents, obtained after a battle by the American Civil Liberties Union and compiled by artist Jenny Holzer into two books titled “Redaction Paintings” and “War Paintings,” my focus was singularly directed at the banal bureaucratic narrative contained in memos, reports, and emails. In page after page of images of Holzer’s colorized silkscreen “paintings” of redacted official correspondence, political debates, pleas for compassion, even consideration for human rights, fall away. What remains is an unvarnished look at the war mentality that takes hold when a nation perceives an “existential threat.”

*

The first men arrived at Guantánamo Bay on January 11th, 2002, wearing blue facemasks and orange jumpsuits. At the time, Guantánamo was considered an extraordinary response to what much of the nation accepted as exceptional circumstances. Suspected terrorists, deemed too dangerous to be brought into the USA, were locked away on an island prison, beyond congressional oversight and the reach of the courts.

When I found Holzer’s books, officials were also describing detainees and asylum seekers as an existential threat. Immigration enforcement has been receiving more tax dollars than all other federal law enforcement agencies—including the FBI—combined. Mass migration was listed among the top threats by the US Southern Command, which covers Guantánamo and Central America, since the War on Terror.

On the border, government officials have sought to physically prevent people from touching US territory, where they can submit their asylum claims. New policies have eliminated or curtailed the possibility of release from detention, which has become a near-default position toward migrants.

“The stench of indignity of this never-legal world seems very similar to me,” said Baher Azmy, Legal Director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, who has represented GTMO detainees as well as recent asylum seekers. The ultimate meaning of GTMO, he said, “is the creation of not an island prison but a lawless strip with nominal access for the public and lawyers.”

Indeed, immigration didn’t provide the justification for subjecting people at Guantánamo to cruel and inhumane treatment and depriving them of liberty and access to courts. War did. When stripped of its immigration veneer, the hieleras and the perreras at the border—ice boxes and dog kennels—find an analogy in the American-made war strategy named GTMO.

*

The letter type on the February 7th, 2002 White House-issued memo bulges, indicating the effect of fax machine processing.

Subject: Humane Treatment of al Qaeda and Taliban Detainees

Based on the facts supplied by the Department of Defense and the recommendation of the Department of Justice, I determine that the Taliban detainees are unlawful combatants and, therefore, do not qualify as prisoners of war…

With that, GTMO detainees were locked away on an island prison, beyond American borders, possibly for a lifetime. Outside of congressional purview or the reach of the judiciary, the detainees entered a legal netherworld. In 2006, in a highly controversial move, President George W. Bush signed the Military Commissions Act into law, which banned GTMO detainees from filing Writs of Habeas Corpus, the ability to challenge their detentions in court. Such extraordinary suspension of habeas corpus had not occurred since 1871, when federal troops were sent to the South to stop the campaign of terror on newly emancipated Blacks.

But in 2008, the US Supreme Court ruled that GTMO detainees could challenge their detention in court. Citing the Constitution, the justices maintained that the Writ of Habeas Corpus was an essential “instrument” suspended only when “in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

Legal recourse for the jailed, they wrote, created a safeguard against the consolidation of power and even authoritarianism by protecting the “delicate balance of governance.” “This design serves not only to make Government accountable but also to secure individual liberty.” Without access to the courts, little stood in the way of arbitrarily jailing anyone.

The ruling in favor of GTMO detainees has resurfaced as a critical tool for attorneys representing asylum seekers. The Trump administration has been aggressively seeking ways to sever asylum seekers’ access to the courts by seizing on a Clinton-era policy known as “expedited removal,” also used aggressively by Obama, which essentially closed the door to judicial review for newly arrived detainees present on the border, including detainees claiming they are legally eligible for asylum.

The once-extraordinary circumstances of GTMO detainees are now commonly cited in US courtrooms, as attorneys argue that their asylum-seeking clients in detention should receive the same access to the courts granted to GTMO prisoners held in the name of war.

In March 2019, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that detainees must have access to the court to challenge their deportation. Without access to the courts, the judges noted, judgments are rendered by an unchecked immigration system that can arbitrarily deny their appeals. However, in a subsequent ruling some experts called “breathtaking,” the judges in the Third Circuit Court declared that non-citizens who are physically but not lawfully present are not covered by the ruling that gave GTMO detainees access to the courts.

On the back of this, the administration stripped access to judicial review across the entire nation, not just the border. Any undocumented immigrants unable to prove they have been in the US for more than two years could be deported without a hearing.

Expanding “expedited removal” across the country, as Beth Werlin, executive director of the American Immigration Council wrote in the New York Times, threatens to “create a ‘show me your papers’ regime nationwide in which people —including citizens —may be forced to quickly prove they should not be deported.”

Do we debate the merits of the detained or the powers of the jailer?

This may appeal to “hardliners” and “conservatives” who demand the swift removal of immigrants; courts, they say, cost money and create unnecessary delays. But consider that between 2012 and 2018, nearly 1,500 US citizens were wrongfully detained by immigration agents, according to an investigation by the Los Angeles Times. On the one hand, access to the courts provides a mechanism to challenge detention, but on the other, it is about reining in government overreach, keeping state power in check. Do we debate the merits of the detained or the powers of the jailer?

The difference is much like reading redacted documents; it is a matter of reading past or through the mysteries, on deciding which way to cast our gaze.

*

Before War on Terror GTMO, there was Immigration GTMO. In the early 1990s, President George H. W. Bush sent the Coast Guard to interdict thousands of Haitians fleeing a coup by boat and detain them at Guantánamo Bay, where their asylum claims were screened. Prior to this, the naval base hadn’t been used as a prison camp.

On the campaign trail, presidential hopeful Bill Clinton denounced this GTMO detention policy as “cruel,” “illegal,” and “immoral.” But once in office, the Clinton administration continued detaining Haitian asylum seekers—men, women, and children—supposedly because they were infected with HIV.

In 1993, a US federal judge ordered the government to release the Haitians from the American base, writing that they had been subjected to “the kind of indefinite detention usually reserved for spies and murderers.”

Within weeks, though, the Supreme Court upheld the policy of interdicting these asylum seekers because it has occurred beyond the nation’s borders. And the US maintained the right to detain refugees at GTMO indefinitely, leaving the island prison open for future use.

By 2018, asylum seekers were arriving by land, not sea. However, once they reached the port of entry, usually a land bridge over the border, Customs and Border Protection inspectors were routinely positioned at the halfway point to prevent them from actually touching US soil. Meanwhile, the US had pressured the Mexican government to prevent asylum seekers from reaching the border; interdiction by land was captured in photos showing Mexican soldiers chasing down women and children.

What constitutes the border has been expanded, blurred, made more ambiguous than a clear boundary on a map.

When I crossed the border from Ciudad Juarez to El Paso, I had to flash my passport twice, once to prove that I wasn’t among the asylum seekers, and the second time to enter the country. Officials deemed the “turn back” policy and “metering”—forcing migrants to wait rather than process them as they arrive—necessary because processing centers were at capacity.

In lawsuits, attorneys have accused the government of illegally turning people back after they had stepped inside a port of entry, acting to “drastically restrict the flow of asylum seekers” and deterring people from asserting their right to asylum with “the false claims of ‘capacity constraints.’”

The government is turning Mexico into Guantánamo.

Government officials have said, in court documents, that even if they were actively preventing people from submitting their claims for asylum (which they don’t say is happening), they would have the authority to do so. They cited the Supreme Court ruling in the case of the Haitians. These people are not within the borders of the US and so… beyond the reach of the courts.

The government’s response is that it is necessary to delay people from submitting their claims because border patrol facilities are overcrowded. Waitlists in some places contain thousands of names. One man, a Nicaraguan I met on the South Texas border, had been sleeping outside for months with a group of Venezuelans, Cubans, and Central Americans while they waited their turn for their claims to be processed.

The effect, said Azmy, among the attorneys representing the asylum seekers, is the creation of a virtual GTMO. “The government is turning Mexico into Guantánamo.”

Once people enter the immigration system within the nation’s borders, most are channeled from Border Patrol processing centers into a system of detention centers run by a network of for-profit companies, local jails, and camps and shelters for children. The overcrowding at Border Patrol centers that officials say forces asylum seekers to wait is due, according to a US Inspector General’s report, to overcrowding further down the detention system.

“Border security” has increasingly become synonymous with locking up anyone who arrives at the border, regardless of the circumstances. Officials, including former US Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen, described asylum seekers not as people asserting basic rights, but as “illegal aliens.” The tenet of asylum as request for refuge, seen through the politics of immigration, becomes a de facto cause for detention.

Until recently, asylum seekers were processed and released and, after a period of time, allowed to work in the US while their claims went through immigration court. Between 2011 and 2013, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) field offices paroled 92 percent of arriving asylum seekers. In 2017, that rate had fallen to single digits—averaging four percent. The decision-maker for parole: ICE itself.

Like GTMO, border detention is not a prison sentence. It’s imprisonment without a set end date. Confinement can last weeks or months or years. Detention is an interlocking system of policies, shelters, and centers created over time. Unlike the criminal justice system, a person is not entitled to legal representation. In detention, the body of one person is submitted to the will of another.

*

Against a dark background, the tightly packed letters glow with a greenish tint.

Date: Thursday August 14, 2003 1:51 am

Subject: Taskers

“The gloves are coming off gentleman regarding these detainees REDACTED has made it clear that we want these individuals broken.”

Coming across this document in May 2019, I was reminded of a conversation I had with Denise Gilman, law professor at the University of Texas at Austin, in the months after the US government launched a widespread program to separate migrant children from their parents at the border. I asked her if child separation was, legally speaking, the most accurate term. “I would call it torture in another framing,” she told me. “The intentional inflicting of severe emotional distress.”

Torture brought to mind electrocutions, waterboarding, sexually humiliating acts. Torture was the image of a hooded man made to stand on a box with wires hooked up to his body. Torture’s other name was Abu Ghraib.

I had filed away her comment until I flipped to a 2003 letter sent via fax to Secretary of State Colin Powell. It read: “The reports indicate that a “handful” of children, described as being between the ages of 13 and 15 years old were “discovered” by the authorities at Guantánamo.” Among them was 16-year-old Omar Khadr, a Canadian national who was transferred to the base from Afghanistan.

“International law and standards recognise the particular vulnerability of children and require, among other things, that children be detained only as a last resort and for the shortest time possible,” wrote Yvan Peeters, who added that it was “ironic” that “the USA … is now treating these children in a way that undermines fundamental protections.” One of the first signatories to the international protocol on the rights of the child in armed conflict was the US.

US Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel

Re: Standards of Conduct Under Interrogation

August 2002

Physical pain amounting to torture must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function or even death. For purely mental pain or suffering to amount to torture under Section 2340, it must result in significant psychological harm of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or even years.”

Solitary confinement, violent force feeding, and suicide attempts had all been aspects of GTMO detention. A decade later, they are reported as the consequences of “border security.”

On the border, inspectors discovered children in detention who had become unable to communicate. One child who could only repeat their own name. Another child who was constantly ramming his head into the wall. A father in a Texan jail who committed suicide after his son was taken away.

The effects of detention were already known when the Obama administration was locking kids up to deter other children from migrating. “Detention is inflicting emotional and other harms on these families, particularly the children…some of these effects will be long lasting, and very likely permanent,” wrote Luis H. Zayas, dean of the School of Social Work at the University of Texas at Austin, who had evaluated immigrant families with children in a 2014 lawsuit filed to challenge the administration’s policy of family detention. Months after children were released, researchers found signs of depression and suicidal ideation.

Recently, inspectors and advocates have found children in conditions described as “horrific.” Babies in soiled diapers. A teenage girl sitting in a wheelchair and slumped over her premature baby. A judge described children sleeping on the floor under lights that are never shut off. A government attorney argued before a panel of federal judges that “safe and sanitary” conditions do not necessarily equal access to toothpaste and soap.

Detention relies on the premise that some people belong in cages.

After inspectors exposed the horror, the government attempted to rewrite the regulations to curtail access to further inspection.

Not one person in any of these detention centers is serving a prison sentence. None are in the criminal justice system. Immigration is a civil court matter and most people who enter without authorization, if prosecuted, face a misdemeanor charge.

Detention relies on the premise that some people belong in cages.

“I do think the common thread is in the othering,” said Jason Dempsey, a retired US Army officer whose tours included Iraq and Afghanistan. “The othering which has always been fundamental to war and populist movements.”

*

Date: Thursday August 14, 2003 11:26 am

Subject: RE: FW: Taskers

As for “the gloves need to come off…” we need to take a deep breath and remember who we are. Those gloves are most definitely NOT based on Cold War or WWII enemies—they are based on clearly established standards of international law to which we are signatories and in part the originators.

…

BOTTOM LINE: We are American soldiers, heirs of a long tradition of staying on the high ground. We need to stay there.

GTMO was eventually recognized as a moral blemish by both liberals and conservatives, a netherworld synonymous the deprivation of liberty and a betrayal of the nation’s core beliefs. In 2007, on the campaign trail, Barack Obama promised to close the island prison, declaring, “In the dark halls of Abu Ghraib and the detention cells of Guantánamo, we have compromised our most precious values.” His challenger, John McCain, supported the end of GTMO as well. “It has become a symbol,” he said. “It may be one of the most nicest places in the world to live in, but it’s become a symbol.”

Public opinion about GTMO shifted, said Azmy, because of efforts by human rights groups and retired military officers to redefine the place. “We developed a narrative about how Guantánamo was the exception and how the Bush administration was going too far,” said Azmy. Together they argued that “this is not who we are, that America kinda lost its way, that we don’t have island prisons.”

This reframing wasn’t achieved by revealing the worthiness of the detainees, or pleading for sympathy. The shift in narrative was not about who “they” are. Instead, through them, “we” decided who we want to be.

Ultimately, Obama did not close GTMO. The government-run island prison persists—forty men remain detained there—as does the legal architecture legitimizing it. And the argument that the dangerousness of these men justifies imprisoning them without access to courts is commonly heard in the realm of “border security.”

Azmy ventured: “Now the conclusion is, Guantánamo is not an exception to the United States, Guantánamo is inherent to the United States.”

*

In early 2019, NBC News published a 2017 memo released by Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon, who said it was leaked by a government whistleblower. It outlined policy options for dealing with migrants arriving at the border, enlisting agencies described by initials: ICE, DOJ, HHS, DHS. Unlike the GTMO memos, the document bore no letterhead, no government stamps. But as with the War on Terror memoranda, this one revealed a government apparatus mobilized to address a threat.

Many of the solutions were strikingly familiar. Interdiction of migrants to prevent them from reaching the nation’s borders. Mandatory detention.

Policy would be formulated to require that migrants remain in Mexico while their cases were adjudicated, keeping them beyond the nation’s borders. This required Mexico’s agreement, and later become a reality.

Like the men picked up and outfitted with jumpsuits and labeled enemy combatants, migrant children who arrived at the border with their parents were redefined as unaccompanied alien children. To do this, parents would be prosecuted with a misdemeanor crime, and that simple action would trigger a cascade of events that broke up families and reclassified asylum seekers as criminals. There was no mention of trauma, no indication of the potential for human pain and suffering. No plan to reunite separated families.

Unlike the GTMO memos, this memo was unredacted. Nothing was hidden.

*

At first, I read through the government correspondence in Holzer’s books for morsels of information. Then I picked through the margins and sender and receiver fields, searching for stray and revealing details.

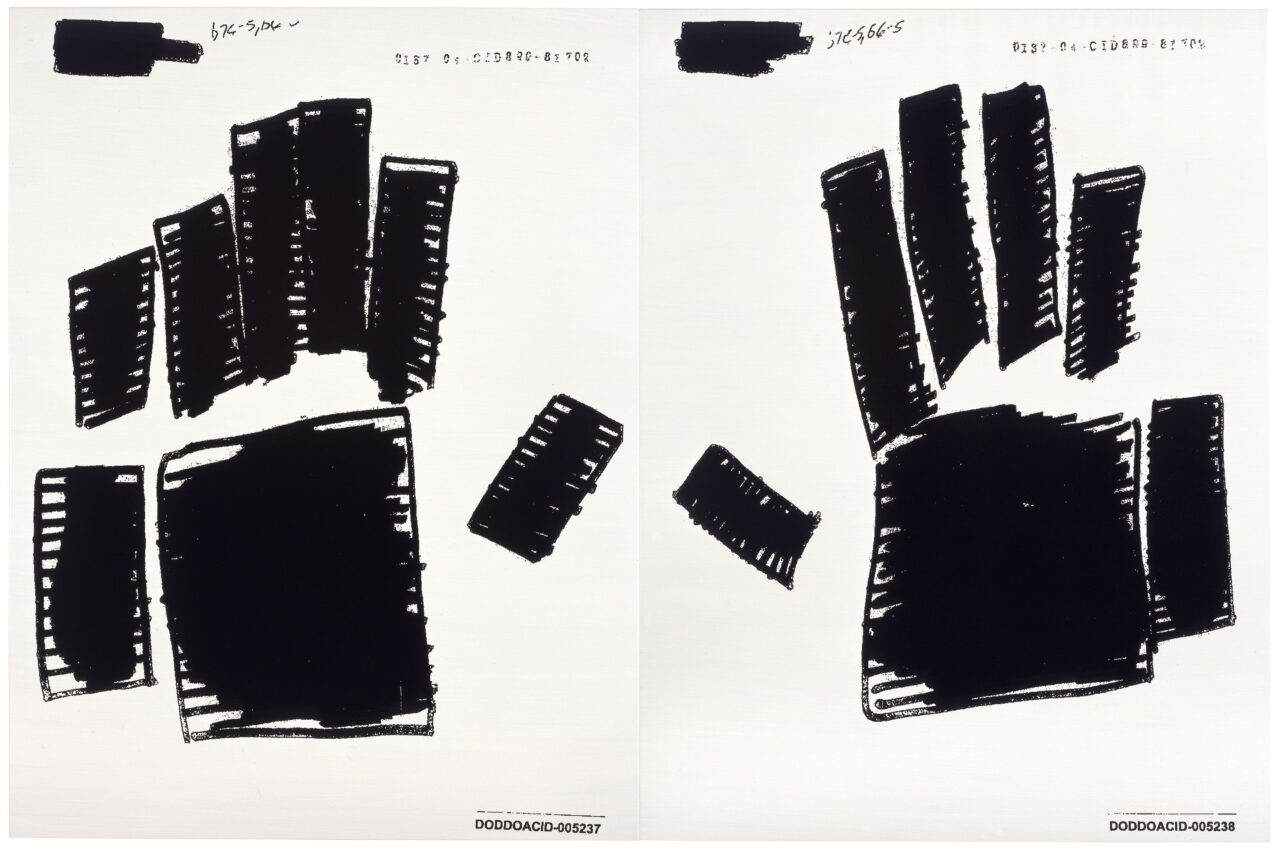

Eventually, I learned to read the redaction itself: the flashes of emptiness, squiggly lines, and large black blocks. I came to see them possibly as Holzer intended for them to be read, as the workings of an unnamed hand, armed with the power to direct our focus, to remove, displace, and erase. On the cover of both books, the redaction blocks are arranged in the form of a human hand. It is at once the hand that conceals and is concealed, the hand that holds the keys and the hand gripping the cell door.

Oil on linen, 2 elements

103.5 x 160 in. / 262.9 x 406.4 cm

Text: U.S. government document

© 2006 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY